This July marks 180 years since the Huskar mining disaster; a distressing and deplorable Barnsley tragedy in which 26 children aged seven to 17 were untimely killed while working at Moorend Colliery in Silkstone Common.

A tale shrouded in coal dust and salty tears of the young people who faced horrors, not only in their working conditions, but also in death, various local community groups have come together to host a commemoration this summer to keep the memory of the lost children alive.

The Huskar 180 consists of Silkstone Heritage Group, Silkstone and Silkstone Common primary schools, the two local churches plus individual volunteers. Starting on the tragedy’s anniversary, 4th July, there will be a range of memorial events taking place in the village.

Disaster strikes 180 years ago

It was Wednesday 4th July 1838, a humid, sunny and warm summer day above the pit top. Over 300ft underground, around 50 children and 33 coal getters were cutting and moving coal, eager to make up time and money following four days unpaid holiday for Queen Victoria’s coronation celebrations.

Moorend Colliery and the adjoining Huskar pit drift were owned by the Clarke family of Noblethorpe, Silkstone. Just six days earlier, the Clarkes closed their mines and hosted a celebration on their parklands for families of the miners.

Little did some know that these would be the last happy times spent together, unaware of the horrors which would subsequently unfold.

Huskar pit, which had a day hole leading into Nabs Wood, was a sloping old mine seam which zigzagged to the coal face and was used for ventilation purposes.

Together with Moorend, 100 children worked down the mines at Silkstone, joined by 70 colliers.

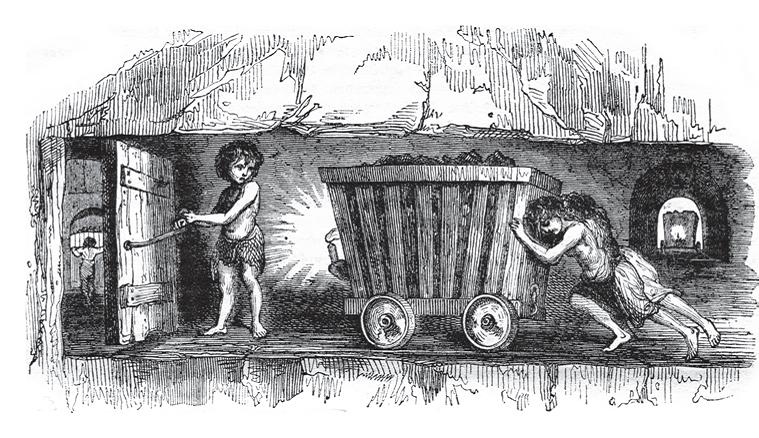

The man of the house, often the strongest, would be contracted to produce a certain amount of coal within a fortnight. He was helped by his wife and children who worked as trappers and hurriers, helping transport the coal from the rock face to the surface via carts and passageways.

Amongst the 50 children working there that day was little Joseph Burkinshaw, just seven-years-old, who had only been there three days. His dad John worked on the coal face and his older brother George, ten, was a hurrier.

Joseph and his fellow trappers earned around sixpence a day, or 2.5p in today’s money. They worked by candlelight for 12 hours, opening and shutting the traps to keep the pit ventilated and let the hurriers through with the coal tubs.

Conditions were dark and damp. Children were cooped up inside for extremely long periods without regular rest or food breaks.

Hurriers were fastened to the coal tubs, pushing and pulling excessive weights with their arms or even heads.

Although it started off as a glorious summer day, the weather quickly deteriorated on Wednesday 4th July and by 2pm a vicious thunderstorm ravaged the village and surrounding areas. Property and land were destroyed. Rivers and streams overflowed.

As the miners worked away down the pit, the water began to devastate the area above. Two engine tenters became concerned at the amount of rainwater and feared it would flood the pit bottom. Steward William Lamb began to prepare for evacuation.

However, the engine and boiler yard had been flooded, extinguishing the fire in the furnace which powered the winder engine to the shaft. Instead, workers would have to be lifted out manually a few at a time.

Lamb instructed everyone to stay together at the bottom of the pit.

Unbeknown to them of what raged on above, the children feared a thunder clap was instead a deadly firedamp explosion.

Having already spent nine hours underground and desperate to save themselves, 40 of the children ignored Lamb’s instructions and set about making their way to Huskar drift, climbing the 15 metres to reach the day hole opening.

Of these children was Lamb’s own son, eight-year-old George.

Two of the four Wright brothers, Isaac and Abraham, 12 and eight, also tried to escape, fearing the same fate as their father John who had been killed by a firedamp explosion the previous year. Their older brothers William and John, 25 and 17, would have worked on the coal face.

What the children didn’t know was that near the top of the entrance was a stream which had become a swollen and raging torrent.

While the children were climbing the slope, the water burst through and poured down the drift, trapping and drowning 26 of the 40 children against the ventilation door through which they had just passed.

Fourteen others managed to escape where they were met by banksman Francis Garnett. His own four children worked at Moorend, one of whom died in the flood.

The two younger Wright brothers also died in the flood, as too did the Burkinshaw boys, with dad John saying it was a pure accident with nobody to blame. He died the following January aged 35, the price of a short life expectancy paid for working underground in the terrible conditions.

After the water had finally subsided, the remaining miners and the bodies of the dead children were brought to the surface where Reverend Watkins and Dr Ellis determined none could be saved.

The children, aged between seven and 17, were taken to Throstle Hall Farm before being transported by cart to their homes across Silkstone, Dodworth and Thurgoland. One or two corpses were left at almost every home.

An inquest was held at the Red Lion pub where a jury inspected the bodies; it wasn’t until after 11pm before any evidence was heard due to the sheer amount of children involved. The unanimous verdict of the inquest jury was accidental death by drowning.

Funerals were then held on Saturday 7th July, attended by thousands. The children were placed in seven graves; 11 girls were buried together in three, with the 15 boys in the other four graves.

Coffins and shrouds were provided by the Clarke family along with a memorial which was erected in the churchyard in 1841.

The Huskar disaster drastically affected the demographics of the local area with families deeply damaged by the loss of children. However, the disaster also had a strong economic effect which would shortly follow.

After news spread of the loss of 26 children, the nation began to wake up and realise the extent of women and children working down the mines in Victorian Britain. Led by Anthony Ashley-Cooper, later Lord Shaftesbury, the scandal brought about a Royal Commission of Enquiry which led to the Mines Act 1842.

This prohibited women and girls from working down the mines and also an age limit for boys of ten years. This ban meant that families with young girls and women moved to other industrial towns such as Huddersfield and Glossop in search of work in service or the woollen and linen mills.

Remembering the lost children

Since the disaster, efforts have been made in the village to remember the lost children and acknowledge the tragedy which has become ingrained in Silkstone’s history.

To bring joy in light of sadness, a commemoration has been held every ten years since 1968. This year, the 180th anniversary will be the biggest event ever hosted, involving the wider community including the two local primary schools.

Local school children will be given talks by author Alan Gallop whose book, Children of the Dark: Life and Death Underground in Victoria’s England, uses the true story of the Huskar disaster as the backdrop to the toils and tribulations experienced by mining children.

Huskar Window

Both schools have been busy creating gardens made up of herbs, plants and vegetables that would have been common in 1838. Designed by John Hislop, the herb garden is shaped as a labyrinth leading out from the pit bottom to the surface, with each herb dedicated to a child. There are also Victorian flower vegetable gardens with some very unusual names and backgrounds.

From Wednesday 4th to Sunday 8th July, Silkstone Church will be open to visitors with floral displays dedicated to the children along with information boards produced by the heritage group which discuss the event, the children and families affected, life in the village and the local mine owners.

Inside the church, visitors can also see the beautiful stained glass window which was produced in 2010 by the villagers under the guidance of stained glass artists, Tina Green and Rachel Poole following the design of local lady Julie Tyler.

The window depicts the disaster, with a lightning bolt, 26 stars in the sky and the names and ages of all children who died in the waves of the water.

Starting at 2.45pm on Wednesday 4th July, roughly when tragedy struck 180 years ago, there will be two services at both memorials; one in the churchyard and the other up at Nabs Wood.

On Thursday 5th July there will be a choir concert at Silkstone Church, 7pm till 9pm.

Nabs Wood Memorial

On Saturday 7th July, there will be a guided tour of the Huskar Trail which starts at Nabs Wood in Silkstone Common and works its way down to Silkstone village. Here, there will be information about points of interest along the way. Sylvia Le Bretton has written two small plays about the tragedy which will be performed at both Silkstone Common school playground and the Red Lion pub.

Silkstone Methodist Chapel will also be open on Saturday 7th with various displays.

On Sunday 8th July, to close the commemoration, a welcome reception for the descendants of the 26 Huskar families and other guests will be held at All Saints Church at 1pm. A remembrance service, led by the Bishop of Wakefield, Tony Robinson, follows at 3pm with all invited to see a performance from Old Silkstone Band.

Other events throughout the week include a Victorian themed sports day and craft workshops, plus performances by Silkstone Common Music Group, the local ladies choir and Silkstone Common School Orchestra.

Churchyard Memorial

Any money raised throughout the event will be donated to Kimbilio; a charity which helps children and families in the Democratic Republic of Congo where some children are still working in dreadful conditions, mining cobalt used in batteries. In other parts of the globe, children are involved in mining for minerals such as salt, diamonds and gems.

Kimbilio run four homes and a day care centre in Lubumbashi to help those affected overcome their dire circumstances and build new hope.

Organised by the Huskar 180 project team, the volunteers are hoping their year of planning will be a community success and would like to uncover more descendants of the families.

Jane Raistrick, whose mother’s family originate from the village, is a member of Silkstone Heritage Group. After starting to research her family history 20 years ago, she discovered she was a descendant of the two Wright brothers, Isaac and Abraham, who died at Huskar.

The group have a file on each of the 26 children and encourage those who believe they are descendants of the families to contact Jane via email on oldtimer11@btinternet.com or join their weekly meetings at the church on Wednesday 10am-4pm.

For more information about the Huskar 180, visit their Facebook page or to find out more about the heritage group see their website: www.silkstonereflects.co.uk