It started with scraped knees and a wobbly hand-me-down bike on a quiet street in Ingbirchworth.

That was the first taste of freedom for a boy who would go on to leave Yorkshire at 18 with almost nothing but a bike and soon find himself racing for Great Britain in velodromes across the world.

Now retired from sport, with an OBE and 24 medals to his name, Ed Clancy has returned to South Yorkshire to give back to the community, guiding families onto their own path to wellbeing.

And in the absence of expectation from the sport he gave his all to for twenty years, the 40-year-old has found genuine joy in cycling again.

Grinning like a big kid on his electric mountain bike flying over jumps in Wharncliffe Woods. Commuting to work on his bike taking the scenic route through Penistone. Pulling on his skin suit and heading out across the Holme Valley with no purpose other than being alone with the sound of tyres on tarmac.

It wasn’t always this simple. For most of his adult life, cycling was a business – and an unforgiving one. Every pedal stroke was monitored, every watt measured, every training session reduced to graphs and gradients.

Inside the pressure cooker of elite sport, joy became another variable to optimise. Marginal gains ruled everything: one percent here, half a second there, the endless pursuit of quantifiable perfection.

The equations behind speed replaced the feeling of it.

Medals came. Plenty of them. Enough to secure his place in sport’s institutional memory as six-time world champion and Yorkshire’s most decorated Olympian.

But he never felt what people assume an Olympian feels. No satisfaction or pride. To him, they were metal reminders of races finished and feelings that never lasted.

“It changes your life but not in the way you think. An existential crisis follows success. We’re not hard-wired as humans to feel satisfied with successes of the past. I reached the pinnacle, but I never felt like I had enough of anything,” he says.

Maybe that belief was born in his early childhood where nothing stayed steady. His biological father walked out when Ed was a toddler and he never saw much of him again.

Before that, Ed says they were a typical South Yorkshire family; his dad worked in the steelworks and his mum stayed home to care for him and older brother, Alex.

When the split happened, Mum was left to pick up the pieces. The boys moved in with their grandparents while she went back into education to train as a teacher to give them a better life.

“That’s where my love of cycling really crystalised,” says Ed. “Grandad was a real adventurer who loved running and the great outdoors and I spent a lot of time with him.”

As a child, a bike meant fun, freedom and independence. He’d use it for a paper round or to get to school and back. On weekends, he’d take himself off exploring on two wheels, going through Thurgoland Tunnel or freewheeling down hills in Denby Dale.

The family had relocated over the West Yorkshire border when Ed was five. After qualifying as a teacher, Ed’s mother got her first teaching job at a school in Mapplewell and she and the two boys moved to a cottage in Kirklees.

With it came a new school and a new set of friends for young Ed and Alex.

Just 19 months apart, the boys couldn’t have been more different as kids. Alex was academic and sociable whereas Ed was quiet and didn’t speak for many years.

“Apparently my first word was tractor. I was pointing at something in the garden that had wheels on it. I was always interested in the mechanical and engineering side of things. English and languages I wasn’t ever any good at, but I got by. But I was alright at Maths and science.”

He was also pretty decent at sport, enjoying team sports like basketball and football. Grandad’s influence as a runner also saw him become a good sprinter and cross-country runner.

But cycling really came into view when Ed’s mum met his stepdad, Kevin Clancy. Kevin would prove to be an exceptional mentor for Ed, giving him a sense of belief and encouragement as a father should.

“He was an optician and I guess you could say he chose to see the best in people. He was younger than I am now when he started dating my mum who had two teenage sons. I always think ‘could I do that’ and the answer is probably not. He was a real grafter but also a decent man and he’s where I get my name from as I changed it by deed poll when I was 18.”

Kevin showed Ed that success in life would only come with hard work. He supported the teen to get his life back on track and have some purpose, encouraging him to join the Holme Valley Wheelers cycling club which would prove a turning point in his life.

As too would Jason Queally’s gold medal win at the Sydney Olympics in 2000. This was Team GB’s first gold in track cycling since 1908 and would change the course of the sport’s recruitment process beyond compare.

British Cycling went on a talent scout mission around schools and affiliated clubs looking for promising young cyclists. They bought a load of static exercise bikes and some transit vans, touring the country in search of future Olympians.

Kids would do three-minute sprint, power and endurance tests on these static bikes and, if they passed, they’d get a cheque for £620 and a place on the talent development squad.

This programme saw hundreds of kids across the UK get into cycling and discovered some of the sport’s most iconic names like the Kennys, Lizzie Deignan, Dani Rowe – and Ed Clancy.

After hearing about the money he could get, 15-year-old Ed asked Kevin to take him to a try-out at Manchester velodrome where he passed the tests and was scouted by British Cycling.

Ed was mentored by former Olympian, Jonny Clay, who was regional talent manager for the North East. Hailing from Leeds, Jonny saw himself in Ed and took the young lad under his wing.

“Cycling is more elitist than ever but even back then in it was inaccessible. Fortunately, I had people who would take me to races, give me a spare set of wheels or some hand-me-down kit.”

Ed worked his way around the junior circuit, developing himself as a rider alongside studying for his GCSEs and later A Levels in maths and engineering. He’d planned on going to Loughborough University to study engineering.

However, in the same week that he’d applied for a student loan, Ed got a letter through the post that would flip the 18-year-old’s plans on its head. It said he was one of six riders that been selected for British Cycling’s brand-new under 23s Olympic academy based in Manchester.

The rest of his family had moved down south, so he’d already been living alone while the family home in Holmfirth was on the market. That same week, it finally sold after 18 months.

So, he tossed nearly everything he owned into a neighbour’s skip, except for the only thing that mattered: his bike. With just a rucksack and no safety net, he pedalled towards the Olympic pathway and away from the past that tried to hold him still.

“That was my meal ticket to go all in. There was never a plan B. I had nothing to lose so I was free to do anything.”

In that inaugural academy line-up were five other young lads by the names of Mark Cavendish, Geraint Thomas, Matt Brammer, Tom White and Bruce Edgar.

British Cycling’s performance director, Dave Brailsford, had given former professional cyclist Rod Ellingworth £100,000 in funding to turn these six lads into Olympic champions or Tour de France winners. It was an experiment in a pioneering year for cycling – a shot at building a medal factory.

“On one hand, we were all determined and desperate to win but on the other hand we were a bunch of 18-year-olds living together in Manchester. We lived on about £3,000 a year so we ate smart price cornflakes and powdered milk. But it was my dream scenario, getting to ride my bike for a living.”

That’s not to say it was easy. Far from it. Rod ran the academy like a military operation. The cyclists were responsible for cleaning and maintaining the bikes, would meet with sports scientists and psychologists, had French lessons, and kept paper training diaries to log how they were feeling each day.

The very first day they wrote their team values and how they’d remain accountable if they broke them – which was code for punishment. And time keeping was essential. If they were even 30 seconds late, they’d be washing cars outside the velodrome after training.

“Every team has a culture and the discipline gave us good grounding. Sport is not a fluffy world and there’s a strict hierarchy in cycling. If the designated road captain gives you an order, you don’t question it and there’s certainly no messing around.”

Over those two years, Ed learned the system and science behind cycling. He also spent a lot of time abroad, particularly in Europe where road racing is huge.

For the last six months of the academy programme, he lived in Germany with Mark Cavendish, with the pair riding for professional road team Sparkasse. But while Cav made his mark on the road circuits, Ed was starting to excel in track cycling, particularly in team pursuit racing.

When the programme came to an end, Ed and the other lads had to step up and take control of their futures.

“We were 21 and had to become like little CEOs. Rod had been a father figure to us but all of a sudden we were having to do it all ourselves, from having conversations and making decisions to sorting contracts and investments.”

Ed signed a professional contract with Belgian team Landbouwkrediet–Colnago and also received lottery funding from UK Sport for being part of the national track cycling team. This enabled him to put a ten percent deposit down on a terraced house in Warrington. Geraint bought a house down the street and the pair would car-share to races and training.

“There’s something beautiful about sport that bonds people; there’s nothing like riding your bike across Mallorca, struggling together for 70 miles. It comes naturally as you spend more time with them than you do your family or partners. I went years without seeing my family, but these lads became my home.”

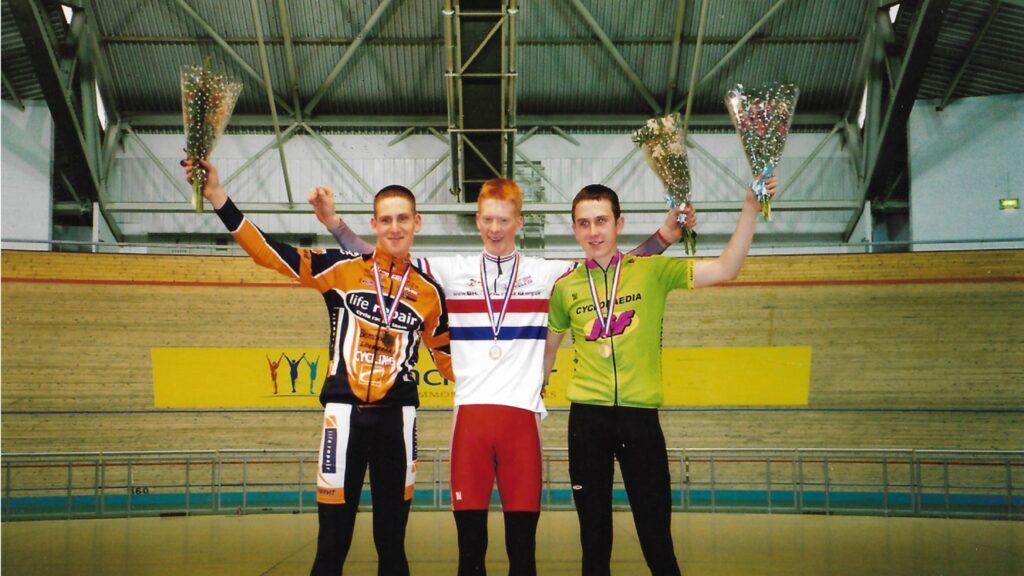

The early days of his career were a tough period for Ed, with him almost throwing in the towel in 2006 not long after taking his first gold medal at the UCI Track World Championships in Los Angeles.

But it’s a good job he stuck it out because his team took the cycling world by storm.

“Between 2007 and 2009, we won everything. And not just by narrow margins. We were beating other teams by six or seven seconds.”

Ed says this was down to the marginal gains philosophy pioneered by Dave Brailsford.

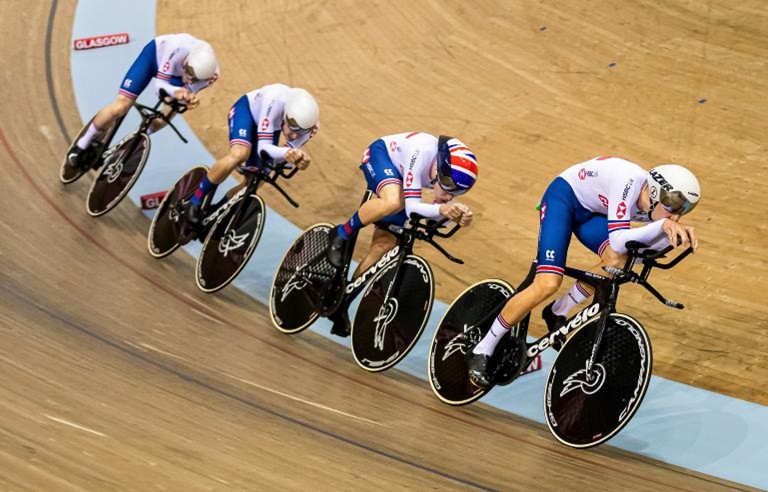

Team pursuit demands obedience to the millisecond. Cycling becomes synchronised machinery: the line, the rhythm, the aero positions, wheels separated by inches and lives interlocked by trust.

The marginal gains concept was all about breaking down everything that goes into riding a bike and trying to increase each element by one percent to accumulate a significant increase overall.

Ed and the other cyclists were guinea pigs who tried everything from different skin suits and bike seats to taking high doses of cod liver oil, wearing electrically heated shorts, and carrying the same pillow around the world to ensure consistent sleep quality.

“Sport is laughably simple when you look back at it. Which of the thousand aspects can you dial up to make you go faster for the quickest, cheapest and most effective impact? It’s why I now question everything. If someone wrote the rules, it means they can be rewritten – except for the laws of physics.”

Win after win meant a perfect storm was brewing ahead of the Beijing Olympics in 2008 but Ed saw his first Games as just another day in the office.

“People put so much focus on the Olympics that they forget about the three World Championships we won before that. I looked at Beijing through a pragmatic lens. The mechanical components were all the same. It was the same 4K event, same four guys, just a different track.”

That no-nonsense mindset might be why Ed and his team – including Geraint Thomas, Paul Manning and Bradley Wiggins – won gold and broke two world records at Beijing, including their own WR they set in the heats.

The road to London was paved in gold, with another world record and gold medal won in Melbourne for the 2012 World Championships. But Ed says the 2012 Olympics was his hardest challenge.

“We were no longer the underdogs and other countries had caught up quickly by copying our marginal gains theory. It’s harder to stay on top and, being on home turf with a hundred million people watching, I can’t explain how much pressure was on our shoulders. But it was also a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

An opportunity that ended in another gold medal and another world record, plus an individual bronze medal for Ed in the Omnium event.

With Rio up next in 2016, Ed wasn’t sure he’d make it. An injury to his spinal disc picked up at training camp saw him undergo surgery in 2015, nine months before the Games was set to begin.

By then he was 30 and knew the recovery would be tough. As well as track racing, Ed was also an endurance rider with Rapha Condor Sharp who were dominating the European road circuit. Long days, long climbs, long periods in foreign hotels where the only constant was the bike leaning against the wardrobe.

But he powered back to being in better shape than ever, resulting in him winning his third consecutive Olympic gold medal, making him the most successful team pursuit rider in British history.

However, that injury would come back with a vengeance at Tokyo in 2021. The relentless nature of the sport, along with him now being an ageing athlete at 36, meant his old injury and sciatica had been aggravated. One morning he woke up and knew that was it – his cycling career was done.

“They say you die twice as a sportsperson. We went from all the news stories being about how Team GB were flying and winning everything to me stood in front of the cameras crying when I had to withdraw from the competition. That was my retirement party.”

Retirement is often painted as liberation for athletes but for Ed it felt like freefall. He’d thrived on the precision of cycling. The structure that had held him together for two decades collapsed.

Without a training plan, goals, or the next race to shape his days, he felt unmoored. He did some coaching with the under 23s, spent a bit of time in research and development for British Cycling, and worked as a consultant for the triathlon team.

“I was blowing around like a leaf in the wind. I never found the same cohesion, meaning or purpose that I had in that wonderful struggle of trying to win at the Olympics.”

But it also did something he never expected: it gave him back the bike he’d lost to power files and performance targets. He could once again ride for moments, for air, for a way to turn his brain off.

“I don’t miss being a number generating robot. It’s all good and well riding an £80,000 bike but you’re not riding for the love of it. It’s all about stats and figures.”

He doesn’t say it resentfully. He understands the necessity. The high performance of elite sport requires sacrifice. But when the pressure evaporated and the rules dissolved, it was somewhat freeing.

That sense of rediscovered freedom now runs through the work he does as Active Lives Commissioner for the South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority (SYMCA).

Since 2023, Ed has been working with South Yorkshire’s mayor, Oliver Coppard, on the Walking, Wheeling and Cycling strategy to create safer neighbourhoods, more routes to opportunity and healthier, happier communities.

Podiums, wind tunnels and national anthems have been replaced by spreadsheets, consultations and meetings with planners. But perhaps for the first time, he feels he’s doing something that matters.

“For my own personal mental health, this job has been the best thing as it’s given me back everything I lost from sport – meaning and purpose. We’ve built a strategy that will add 40,000 years to the lives of people in South Yorkshire. If I can be part of the puzzle to make families healthier so they can spend more time together, then that’s worth everything to me.”

He knows what it means for a bike to be an escape route or a lifeline. Now he wants to make sure everyone – every child, commuter or lost teenager – has access to that freedom.

Along with his work at SYMCA, Ed also founded the Clancy Briggs Cycling Academy for children and young people and is the new managing director of the British Cycling Foundation which helps gets kids on a bike in underprivileged areas.

And yet, if you ask him what he’s proudest of, he’ll shrug. Not out of modesty but habit. Satisfaction still eludes him; perhaps it always will.

“The older I get, the more I believe that your most enduring mark of success isn’t money, medals or how many spare bedrooms you’ve got. Individual glory doesn’t matter. It’s about being a kind person and having a positive impact on society.

“Those medals no longer have any value in my life. The only way they’re valuable is by giving me this platform I’ve got now.

“I recently went to give a talk at a school where a lot of the children had additional needs, but it was so good to see them engaged and have aspiration. Not necessarily aiming for the Olympics but to just do something with their lives, whether that’s being a builder or an engineer. It was the best visit I’ve ever done.”

Not every champion’s greatest victory is won at the finish line. What Ed has now is movement, momentum and a life that, after everything, keeps rolling forward for the good of the community.