In the summer of 1940, as Britain braced for invasion, two brothers from Barnsley climbed into their Spitfires, bound not just by blood but by the desperate fight for their country’s survival.

Among the hundreds of young men who held the Luftwaffe at bay during the Battle of Britain were John and Hugh Dundas from Cawthorne.

In aerial duels above the English Channel and Europe, the brothers fought with their respective squadrons in a militant manner, each sortie carrying the weight of uncertainty.

Day after day, they rose into skies darkened by enemy bombers, knowing the odds were stacked against them. Each mission could have been their last, yet together they carved out reputations as fearless fighter pilots in one of history’s most decisive air battles.

In November 1940, tragedy ultimately struck: the elder brother, John, was lost in action, one of so many young pilots whose lives were cut short. John shot down Major Helmut Wick, Germany’s number one air ace but, an eye for an eye, was quickly taken out by Wick’s wingman, Rudolf Pflanz. His body was never recovered.

The younger Dundas brother, Hugh, scarcely more than a boy himself, pressed on with defending the nation and rose to become one of the youngest group captains in the RAF.

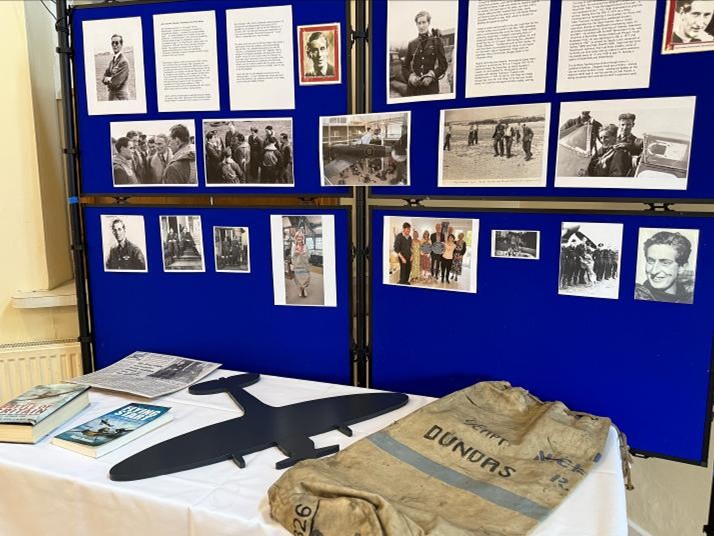

On the 85th anniversary of Battle of Britain Day on 15th September, the village they grew up in honoured them with a blue plaque outside their childhood home. The project was organised by residents Sharon Pitt and Derek Housley, with support from Penistone Ward Alliance and Cawthorne Parish Council.

Hundreds of people gathered in Cawthorne, including their descendants and current members of their RAF squadrons, to pay tribute to the courage, sacrifice, and the bond between brothers who helped defend Britain at its darkest hour.

Long before they became aces in the Royal Air Force, John and Hugh were just boys chasing model planes across fields in Cawthorne – or riding noisy motorbikes through the village, much to the chagrin of other residents.

John, the eldest of five Dundas children, was born in 1915. Five years and three sisters later came Hugh, born in 1920.

Hailing from Barnburgh in Doncaster, their family moved to Cawthorne in 1924 to Dale House on Tivy Dale.

Their parents were Frederick and Silvia Dundas. Frederick was a colliery director who had shares in pits across Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire, including Cadeby, Denaby Main, and Roundwood.

Frederick was a descendant of Scottish nobility; his mother, Alice, was the daughter of Charles Wood, 1st Viscount Halifax and Lady Mary Grey, daughter of former prime minister, Earl Grey. Charles Wood was landed gentry who owned Monk Bretton and Alice grew up at Hickleton Hall in Doncaster.

Alice married the nephew of Lawrence Dundas, 1st Marquess of Zetland; Lawrence’s daughter, Maud, married Billy, the 7th Earl Fitzwilliam of Wentworth Woodhouse.

Frederick sent his boys to boarding school at Stowe. John, a highly academic and intelligent young man, gained a scholarship to Stowe aged 12, then went to Christ Church, Oxford at 17 on another scholarship, graduating in 1936 with a first in modern history. His studies then took him to Sorbonne in Paris and Germany’s Heidelberg University, two of Europe’s most prestigious institutions – again, on scholarships.

On completing his education, John returned to England where he became a foreign affairs journalist at the Yorkshire Post. His first cousin once removed was Lord Halifax, foreign secretary in 1938, who was said to have helped him land the role.

John covered pivotal events, including the Munich crisis in Czechoslovakia, then the Rome meeting between Lord Halifax and British and Italian prime ministers, Neville Chamberlain and Benito Mussolini.

Having grown tired of journalism, John looked for a welcome distraction. Aged 23, he self-funded his pilot license and volunteered his weekends as a pilot officer with the 609 (West Riding) Squadron of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force. The commanding officer was his godfather, Harald Peake, a colliery director who worked with his father.

By this time, Hugh had left Stowe. He’d been articled to a solicitor but, spirited and slightly rebellious, Hugh joined the Auxiliary Air Force like his older brother. Despite failing the medical exam three times, he was assigned to 616 (South Yorkshire) Squadron. The day after his 19th birthday, in July 1939, Hugh was commissioned an acting pilot officer.

As Mussolini’s fascism seeped through Europe, and Churchill’s prophecies about the dangers of Nazi Germany were seen to be coming true, the 21 auxiliary squadrons and their volunteer reservists became a vital part of the RAF’s forces.

The two Dundas brothers were called up to the war efforts with their respective squadrons; John was based at Middle Wallop in Hampshire, while Hugh, who had garnered the nickname ‘Cocky’, was over in Leconfield near Beverley.

They were never too far from home, evidenced by one village folklore tale of how one of them – though it’s never been proven which one – reportedly landed a Spitfire in the middle of the A635 near the junction of Tivy Dale. While they popped home for a coffee with their parents, a group of villagers turned the plane around ready for them to set back off.

John and Hugh both embodied the unyielding spirit of the RAF. With their respective squadrons, they both took part in the Dunkirk evacuation in May 1940, during which John destroyed three German aircraft.

With France defeated, Germany turned to its next objective: forcing Britain out of the war. Hitler’s plan for invasion was Operation Sea Lion, which required air superiority over the English Channel and southern England. This led directly to the Luftwaffe launching the Battle of Britain in July 1940.

Again, the Dundas brothers and their auxiliary air force comrades were deployed throughout the three-month battle that involved 1,500 aircraft.

Hugh found himself flying alongside the legendary Douglas Bader and was very much in awe of this ace who continued to fly despite having had both legs amputated.

Letters home spoke little of the danger, but in the mess halls and on the airfields, they lived with the constant reality that a single mistake – or a moment of bad luck – could separate them forever.

In August 1940, Hugh wrote home that he’d been shot down over Dover, having bailed when his aircraft exploded at 12,000 feet in the air. He told his mother not to worry as he’d had an ‘enjoyable parachute descent’ and, with just a dislocated shoulder and lots of splinters in his leg, he was relatively unscathed and was only out of action for a few weeks.

Meanwhile, John had quickly risen to ‘ace’ status himself; by August 1940 he had nine confirmed kills. Racking up enemy aircraft at a rate of almost one a day, a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) came in October that year.

However, his gallant efforts were cut short when he was killed in action on 28th November 1940, mere moments after shooting down Helmut Wick, the Luftwaffe’s highest scoring ace. He was just 25.

At the time of his death, John was credited with 12 confirmed kills, four probables, two shared and five damaged. He was posthumously awarded the Bar to his DFC and his name appears on the Runnymede Memorial, as well as the war memorial in Cawthorne. A Spitfire he flew, R6915, is on display at the Imperial War Museum in London.

John’s magnificent fighting spirit inspired so many others to continue the fight against the Nazis, including his brother Hugh.

In spite of his grief, Hugh remained in active service throughout the war, rising through the ranks to flight commander, commanding officer and squadron leader. He spent time in a training unit, before joining the Firebirds, one of the RAF’s oldest and most successful squadrons. Hugh was posted to the Mediterranean, serving in Tunisia, Malta and Italy.

He was awarded his own Distinguished Flying Cross in August 1941 for ‘unflagging courage in the face of the enemy’ followed by a Distinguished Service Order in March 1944. Just three months later he was promoted to group captain aged 23, the youngest in the RAF.

Hugh survived the war, with four enemy aircraft destroyed, six shared destroyed, two shared probables, and three damaged. He retired from the RAF but continued with the auxiliary air force until 1949.

After his military career ended, he again followed in his brother’s footsteps, becoming an air correspondent for the Daily Express. He then moved into TV and radio broadcast, joining Rediffusion in 1961 where he oversaw the boom of colour TVs. Hugh also served as chairman of Thames TV and Macmillan Cancer Research, and was a deputy lieutenant and high sheriff of Surrey.

In 1977 he was presented with a CBE before receiving a knighthood ten years later. Sir Hugh died in 1995 aged 74, leaving behind his wife Enid, three children and eight grandchildren.

Two of his grandchildren travelled up from London to Barnsley for the plaque reveal, along with his daughter-in-law Jenny and nephew Sir Ian Muir.

Granddaughter Lucy, who was only nine when her grandfather died, shared fond memories of how Hugh was always smiling and would dole out ice lollies to his brood of grandkids at bathtime.

The Deputy Lord Lieutenant for South Yorkshire and vicar of Cawthorne, Reverend Canon Keith Farrow, was also in attendance.

In his speech, he said: “The Dundas brothers’ story is one of fraternal devotion amid unimaginable odds. Together, they represent the Battle of Britain’s triumph, where 544 RAF pilots gave their lives to repel the Luftwaffe.

“John and Hugh Dundas were not just pilots; they were guardians of liberty, sons of Yorkshire, and eternal symbols of the RAF’s motto: Per Ardua Ad Astra – Through Adversity to the Stars. May their spirits soar forever.”

As we head towards Armistice, the village will continue to remember the Dundas brothers, as well as the other 29 names on Cawthorne’s war memorial. Cawthorne Crafty Ladies are doing a remembrance trail to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of WWII.