When a letter from the Cabinet Office came through the letterbox at her home in Harley, stating that she was to be made a Member of the Order of the British Empire in King Charles’s 2023 New Year Honours List, Cynthia Shaw put it down in semi-disgust.

Thinking it was a scam, she grumbled that they had another thing coming if they thought she was handing her bank details over that easily. But on second reflection, she realised the paper was actually quite posh, so she phoned the Cabinet Office to check its authenticity. Well, as she rightly says, you can never be too careful these days.

“I told them someone purporting to be from their department had sent me a letter saying I had been awarded an MBE. When I gave them the reference number, they asked me if I was indeed Mrs Cynthia Shaw. That flummoxed me a bit. Then I made a fool of myself by asking if they had the right person. They reeled off some of the things I’d been commended for and I couldn’t quite believe it myself. It humbles me beyond belief. There are millions of volunteers out there who never get recognised, so why me? How’s that happened?”

But Cynthia Shaw is not a woman to be underestimated. ‘This MBE thing’ as she calls it when we meet, for services to the community in Rotherham, is so richly deserved for a person who has spent her life advocating for others. If you looked up the word stalwart in a dictionary, Cynthia’s picture would be there.

“I don’t like injustice and I won’t be beaten. Someone once told me I’d have made a good Suffragette, but I wouldn’t have gone on hunger strike as I like my food,” she laughs. We’re tucking in to fruit scones and cream filled pastries while we chat, made fresh that morning especially for our visit.

Across her eighty-plus years on earth, there aren’t many people she hasn’t supported. Miners, pensioners, the disabled are just a few to have had Cynthia in their corner, going up against politicians and Prime Ministers in her fight for better outcomes.

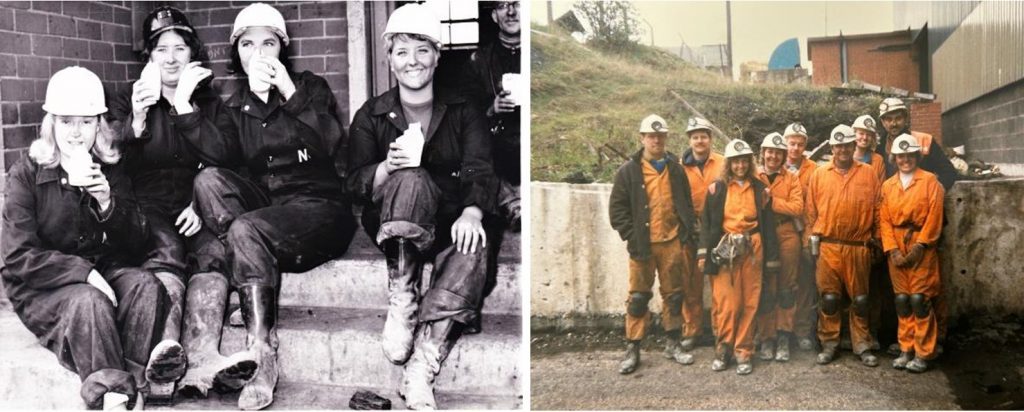

Her working life was spent as a woman shattering glass ceilings in a male-dominated industry. She worked for the National Coal Board for over 35 years, first in the wages office at Rockingham Colliery before moving to the NCB’s pensions and insurance service when the pits closed.

Then two heart attacks when she was 50 changed her outlook on things and she retired the following year. But she certainly didn’t put her feet up.

Cynthia has spent the last thirty-odd years volunteering as a magistrate, parish councillor, public governor for Rotherham Hospital, and trustee of Wentworth Charity. She’s also tirelessly campaigned for almost fifty years to improve for road safety on the A6135 from Chapeltown to Hoyland that sits directly behind her house.

Even now, she never stops. Her diary is more or less full every day with meetings or gatherings. When we met, she’d just finished making jars of marmalade and knitting a pile of dishcloths for the raffle at Harley Mission Rooms’ charity Easter fair and tells us how she’s serving up pie and peas for 30 of the village’s old people the next day. She’s 83 herself.

“Sometimes I forget how old I am but my mam used to say, ‘Allus get up wi’ a purpose’. When I was working I had time for nothing. Then after I retired I still had the energy and ability to help others.

“I’ve had a charmed and comfortable life, but much of it has been spent feeling responsible for others and responsible for providing for myself.”

Born in August 1939, just before the start of the Second World War, Cynthia spent her early childhood in a two-bed house in Wroes Yard, just off Queen Street in Hoyland Common. Her neighbour was A Kestrel and a Knave writer, Barry Hines, who she went through school with.

Like many families during the war years, money was tight. Her dad, John Brammah, worked at Rockingham Colliery and mum Edith was a housewife who looked after Cynthia and her two younger siblings, Peter and Denise. The house was condemned but the family was only rehoused once they were classed as ‘morally overcrowded’ – when Cynthia reached the age where she needed a bedroom of her own for privacy.

John was a union rep at the pit, which is probably where she gets many of her qualities from. He was strong but fair. He’d been injured at work but never relied on handouts or free school meals. He instilled in his children great work ethic, with all the Brammah brood having jobs from being kids.

But Cynthia was a bright girl. She passed her eleven-plus exams and won a scholarship at Ecclesfield Grammar School. Edith convinced her husband that Cynthia ought to go, having missed out on opportunities herself as a child.

“Grammar school was beyond my parents’ vision, beyond their horizon. You could only get the uniform at Cole Brothers in Sheffield and Mum had never even been to Sheffield in her life.”

John agreed to let Cynthia go, but she quickly realised she was different to most of the students there; they had money behind them.

“One time a school friend invited me to her house after school to watch Wimbledon on TV and her mother had left us a bowl of strawberries and cream each. The first thing I noticed was they had carpets. Our house had a gas mantle, stone flag floors, no hot water, no bathroom and just an outside toilet that we shared with other houses.”

But her humble background had made her tough. She’d spent her youth playing in the street with the lads, so was always picked for the hockey team as they knew she’d get stuck in and get the ball through. It was at school that Cynthia realised that if you’re good at something and you work hard, people will always want you.

The headmaster of Ecclesfield Grammar could see true potential in Cynthia and in her final report he said she would make her way in life as a leader and significant contributor. He encouraged her to stay on at school for sixth form but was mindful of her home situation.

Her dad had suggested a job at the coal board and she started at 15 once she received the five O-level exam results needed to secure a job in the colliery offices.

She joined the wages office at Rockingham Colliery in 1954 and stayed there until the pit closed in 1979 when Cynthia was 40.

Using her grammar school maths, Cynthia did all the taxes in her head – which was pounds, shillings and pence back then. One time, a miner questioned his take-home pay, arguing he’d paid too much tax. And Cynthia had an insight into why.

After telling the miner that if he had a big top line wage he’d have to pay a lot of tax, her dad made her go down the pit to the coal face to spend just a short time in those conditions where the miners earned their crust.

“I always tried to measure up to my dad so I didn’t back down or show fear. But it was horrible. Dad was tall and thin so he had to keep stooping and bending. Then we got down on our haunches and crawled into this small hole leading to the coal face where the shearing machines started started and the conveyor belt chains were rattling.

“It was dark, there was dust puthering up, and the noise was like hell. Totally constricted space, it was horrendous and we were conscious of the ever present danger. Still to this day, I have lifelong respect for any man who ever walked into a pit. Miners were brave, strong men.”

When it was announced in 1979 that Rockingham Colliery was to close, Cynthia decided to change careers after 25 years in the wages office. By this time she had a young son, Kelvin, and needed to think about their future stability. She knew that other collieries would follow suit and shut, so there was no point in her being transferred to another pit. Instead, she applied for a job at the NCB pensions and insurance centre in Sheffield where she knew there would always be a job.

She was appointed insurance office manager, leading a team of many staff. In her new role, Cynthia began to use her voice – and inside knowledge about what miners were like – to help protect their futures once the pits had shut. She was invited to meetings with government ministers about paying out redundant miners and upskilling them for new careers. Cynthia argued that the process of endless form filling would impede miners as so many weren’t used to pen and paper.

“I think it was the right place, right time, right temperament. But I did ask why they gave me the job and they said it was because I make things happen. It was a fantastic job but also very hard, stressful and demanding.”

The stress of the job would contribute to Cynthia having two heart attacks when she was 50, so she made the decision to take early retirement in 1990 aged 51 after 35 years in the coal industry. Her husband Barry, who had also worked for the coal board as the computer centre customer service manager, had already retired and they planned to do a world tour, visiting the likes of China, Japan and Australia.

Back on home turf and with plenty of free time on her hands, Cynthia threw herself into various philanthropic endeavours.

She became a magistrate on the Rotherham panel until she had to retire at 70 in 2009. During her twenty-year post, Cynthia dealt with cases about everything from TV license or speeding fines to those involving children and animal cruelty and was known for standing up for the rights of victims.

“I don’t purport to sit in judgement – who am I? But it is the law of the land and someone has to do it. I enjoyed it in a way as I felt instrumental in promoting a law-abiding community. I always tried to impress upon defendants that there was a victim of their crime.”

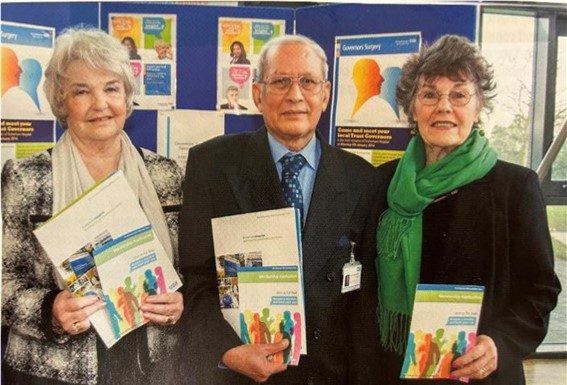

Cynthia also became a public governor at Rotherham Hospital where she launched the governors’ surgeries in 2014 – something that is still in place today to gain feedback from visitors to the hospital. She gave up the role to care for her husband Barry who sadly passed away four years ago.

She is also chairman of the patient participation group at Walderslade GP practice in Hoyland where she led a petition in 2017 for double yellow lines outside the surgery after seeing a young man in a wheelchair be forced onto the road due to cars mounted on the pavement.

But her biggest influence has to be the campaigning she has done as chair of the A6135 Accident Reduction Group. Cynthia’s back garden overlooks the road that leads from Chapeltown to Hoyland which is England’s second most high-risk route. She has collated an extensive catalogue of every incident that has occurred since she moved there in the 1970s, with 15 fatalities and endless accidents on that one stretch of road.

A fatal crash in 2008 involving three teenagers led to safety measures finally being installed two years later.

Cynthia wrote to the coroner to say it was high time something was done. She was invited to give evidence at the inquest, detailing how a similar accident had happened in 1995 involving another three young people. The coroner made a number of recommendations under Rule 43 of the Coroner’s Rules to prevent further deaths.

A large tree was felled, and foliage was removed to improve visibility on the Hood Hill bend. A crash barrier was added, along with bollards and new road markings. There have been no fatalities since these measures were put in place 13 years ago. In recognition of her efforts, Cynthia was invited by her MP, John Healey, to a community heroes reception at Parliament where she also met with the then Prime Minister, Gordon Brown.

Since 2012 Cynthia has been a trustee of the Wentworth Charity, which supports residents in the village, and has also been a parish councillor for Harley since 2017.

“The work never stops. I once had a phone call at 9.30 at night telling me I need to do something about the horse muck on the pavement. Well, I was in my nightie so I said shall I come out with a shovel, love?”

Over the last six years, she has fought to save Harley Mission Rooms from shutting, raising over £150,000 to secure the future of the 1887 building.

She had us doubled up with laughter as she told us a tale about how she secured £14,000 from the Yorkshire North and East Ridings Freemasons and, in gratitude, kissed the grandmaster during their AGM at Harrogate. “There was utter silence. It’s never been done before or since.”

She also received a grant from London-based livery company, The Weavers, after persuading them to reassess their stance of not supporting projects up north.

“The Mission Rooms are vital to the village. We’ve only got one pub and not everyone wants to go in there every day. So, I was determined to ensure it wouldn’t close. It’s a lot of money to raise for an old woman and I’ve never done anything like it before. I once raised £400 to buy wheelchairs for injured miners in the late Eighties but nothing compared to the scale needed for the Mission Rooms.”

The money was used to renovate the building, with new windows, a new kitchen area, and a new heating and air conditioning system. A roller door has also been added to section off the religious area of the building so that the venue can be dual purpose for Sunday religious services and daily community activities. It is now available to hire for concerts, parties and community groups, bringing in extra revenue to sustain the building.

In between her busy schedule, Cynthia will have to find time to attend the investiture when she formally receives her MBE.

“I’m not sure what will happen yet or when, but I am told it will be after the Coronation and all probability it will be King Charles presenting the awards at either Buckingham Palace or Windsor Castle as these are his first New Year Honours as monarch.”

Once a date is confirmed, Cynthia hopes to take her son, Kelvin and two grown-up grandsons, Thomas and Samuel, to the ceremony.