There’s something deeply soothing about listening to the bard of Barnsley, Ian McMillan. Quips and quotes ripple from his brain and roll off his tongue the way the waves lick the shore, lulling you into a comforting trance.

Any nerves about having to tell the story of a storyteller are soon washed away, like we’ve arrived back home and been reunited with an old friend.

He’s soon got us laughing, tears streaming and notebook abandoned, as he tells us outlandish stories about being asked to write a sonnet for a well-known bleach brand and perform it on a giant wooden toilet in Leicester Square. Or the time he was booked to do a talk after being muddled up with Ian McKellen.

“’Well, at least you’re still a Shakespearean actor’ they said,” he says nonchalantly while sipping what he says is the best espresso in Barnsley. “The trick is to always say yes as it leads to adventures.”

Hardly saying no has led to him becoming one of poetry’s most recognisable faces, writing countless poems and umpteen anthologies in his forty-year career – the lion’s share being an ode to his life in Darfield.

His ability to talk himself home has seen him be the poet in residence of Barnsley Football Club since 1997, become Barnsley Museum’s Poet in Lockdown, and be given the Freedom of the Borough of Barnsley in 2018.

That distinctive northern accent that seeps into the rhythm of his poetry has been the voice of language and literature programme The Verb on BBC Radio 3 for the last twenty years.

“I get asked a lot if I maintain a base in Yorkshire and I say yes, but I call it my house. I’ve always lived in Darfield and my home is 200 yards from the house I was born in. People think – or presume – I should be in London, but I can write from anywhere.”

It is thanks to his birthplace in Barnsley that Ian owes his career. He was afforded an education under the West Riding County Council at a time when Sir Alec Clegg was council chief. Sir Alec abolished the 11+ to ensure all children had a continuous education regardless of academic ability and fervently encouraged creativity through music, theatre and arts.

Ian moved up from Low Valley Junior School to Wath Grammar School which is where he first knew he wanted to be a writer.

“Lots of people point to one teacher who had an influence on their life and for me it was my English teacher, Mr Brown, who was tall, had a beard and wore a fantastic green corduroy suit. He was only there for two terms, but he got me back into writing by encouraging the class to write about what’s around us, what we saw in the school yard or on our way to school.

“I only ever disagreed with him on one thing. I once submitted an essay – spelt S.A – by ‘Ian McMillan, Future Nobel Prize in Literature Winner’. And he told me Nobel Prize winners don’t come from Barnsley.”

He might not have the iconic gold medal, but Ian has still had a great benefit to mankind as the people’s laureate. He’s become somewhat of a national treasure, a figurehead for aspiring writers who want their work critiqued by Mr McMillan.

His proudest accomplishment is seeing his own son, Andrew, follow in his footsteps to become a rising young poet and writer who won the Guardian First Book Award.

Ian’s own intrinsic poetic licence ingrained in his DNA could be attribute to seafaring love letters between his parents during the war.

Dad John was a Scottish lieutenant commander in the Navy, while mum Olive moved from Great Houghton to Lancashire to volunteer with the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. Single service people were encouraged to write to each other for morale, so John and Olive became pen pals.

A stranger’s scrawl would turn into a manuscript for marriage. But with John sailing the world, the couple only saw each other three times before the wedding, and even that day didn’t go to the letter.

“My dad would send a telegram saying ‘request leave’, and Mum would reply saying ‘leave denied’. In the end she went AWOL to meet him as he only had a 48-hour pass. He’d travelled from Plymouth to Peebles on the Scottish borders and Mum got the slow train up there. Then she got off at the wrong station so they only had an hour to get married and the register office queue was huge.

“The next morning, my dad went straight to Shanghai for two years and Mum was arrested and spent two weeks in a military prison. They always used to exaggerate some parts of the story with fiction, such as saying someone brought Chinese silk to make Mum a dress. That’s probably where I get it from.”

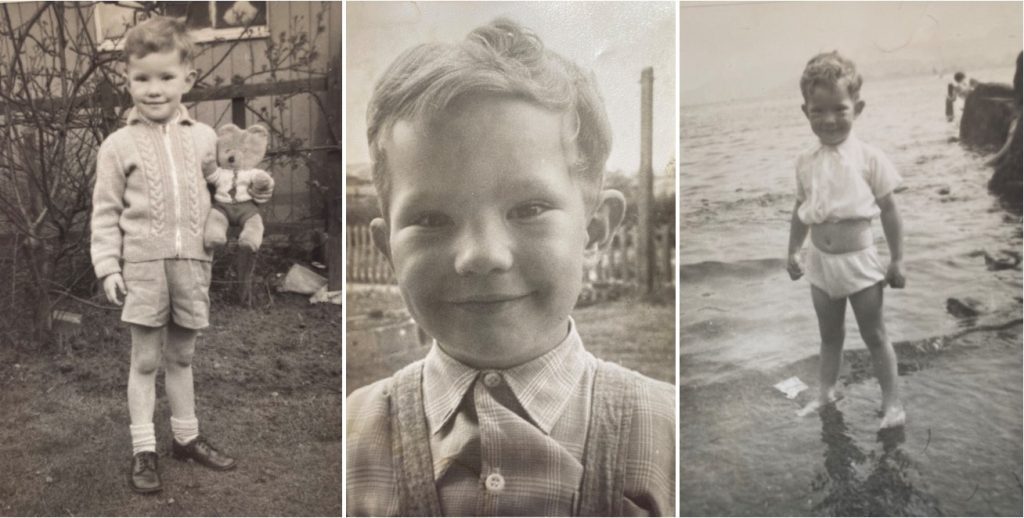

After the war John spent another 12 years in the Navy while Olive moved back to Barnsley and settled into life as a mum. Ian and his older brother, John Jr, had an idyllic childhood growing up in Darfield, with memories of driving round Great Houghton on Sundays with their dad telling stories, or hiding from Mrs Dove the Darfield librarian and seeking out all the Enid Blyton and Biggles books.

In his teens, Ian combined his love of writing with music, launching Barnsley’s first folk band called Oscar the Frog.

“I was the drummer and played Tupperware with knitting needles. We became more of a Ceilidh band but I got the sack as the rest of the group thought I’d lost interest so instead I formed a folk and poetry duo called Jaws with Martyn Wiley.

“It felt natural to be a writer but all I wanted to do was stand up and perform. I only went to university because my parents thought I should; you couldn’t make much of a living from performing or writing.”

After graduating with a modern studies degree from North Staffordshire Polytechnic, Ian got a job on a building site in Chapeltown then worked at the Slazenger Factory in Barnsley making tennis balls. By this time, he’d married his childhood sweetheart, Catherine, who he met at school and the pair would go on to have three kids: Kate, Elizabeth and Andrew.

He kept on writing and quit his job to become a freelance writer, a clause for receiving an £800 grant from the Yorkshire Arts Association. With freelance work sluggish, he then found a job with Dearne Valley folk singer, Ray Hearne, at the Workers’ Educational Association delivering poetry workshops to schools.

His first break came in 1982 when his debit book, The Changing Problem, was published.

“I was always sending stuff off to poetry magazines for consideration and used to put cardboard in the envelope to keep the paper flat. I’d take it to Darfield post office where the postmaster would say, ‘Is this another masterpiece, Ian?’”

A succession of books followed, combining memories with observations that reveal his inimitable view of the world.

His latest book, My Sand Life, My Pebble Life, is made up of memories of coastal visits from childhood holidays by the sea to visiting his mother-in-law’s caravan in Cleethorpes.

“After Neither Nowt Nor Summat was published in 2016 I said I wouldn’t write another book as I was semi-retired. But I was asked to write an introduction to a book about the coast and then Bloomsbury asked if I would write a 50,000-word book about the coast. I prefer writing shorter things, so I suggested 50 1,000-word stories.

“I planned to do a gig in every village hall in England with Luke Carver Goss and while there I’d visit the nearest coast and write about it. But then the pandemic hit and that thwarted all the plans. So I wrote about my memories instead.”

Ian’s work is nothing if not relatable, engaging everyday audiences in everyday places.

Requests for his Yorkshire dialect-infused limericks and Haikus come in from here, there and everywhere, with Ian having been commissioned to write about everything from football to fizzy water. It comes with the territory of being a wordsmith, the ability able to convey the magic of the mundane.

He’s amassed a captivated following on Twitter where he shares a poetic look into his semi-retired routine in and around Darfield: an early riser with the 5am club; the first cup of tea of the day; his four strolls a day; journeys on public transport; volunteering at Darfield Museum; and visits from his four grandkids Thomas, Isla, Noah and Louie.

“I like Twitter as it makes you think hard and gets your brain going. I’m always out walking and tweet about what I see. I never have days where I can’t think as that would be terrible.”

My Sand Life, My Pebble Life is available at The Book Vault, 7 Market St, Barnsley town centre at £10.99

Or via Amazon or Waterstones