In the world of football, players and managers often steal the headlines. But behind every club’s rise, revival, or reinvention stands a figure whose influence is quieter, yet no less crucial: the chairman.

Tony Stewart OBE has been the steady hand at the helm of Rotherham United since 2008, guiding the club through turbulent seasons and moments of sheer euphoria.

He took over a club that was on its knees. Homeless, debt-ridden, and crippled by two periods of administration in 18 months, it looked like the Millers had ground to a halt.

But Stewart, a self-made businessman from Sheffield with a sharp mind and a stubborn streak, saw not ruin, but a new business opportunity.

What followed wasn’t just a boardroom rescue mission. It was a full-scale resurrection.

From laying the first brick of the AESSEAL New York Stadium to celebrating multiple promotions and bringing pride back to the town, Stewart’s legacy of how he saved a crumbling club from oblivion is now firmly stitched into the club’s 100-year history.

His story isn’t just one of business acumen or strategic leadership, and neither is it one of following a sentimental boyhood dream. It’s a rare insight into what it truly means to lead a football club not only with cash, but with conviction.

Fans might have been critical of the club’s perceived stagnation, the perpetual transition between the Championship and League One. But 17 years and £60 million of his own money later, Tony remains as driven and committed to underwriting the club as ever.

His path to rebuilding Rotherham United was forged long before the roar of the terraces at New York became part of his daily life.

Born in High Green, Sheffield just after the end of WWII, Tony didn’t take the conventional route into football. Living in the blue side of Sheffield, he loosely followed Sheffield Wednesday as a youngster, but his main focus was athletics, his sights set on becoming a professional runner.

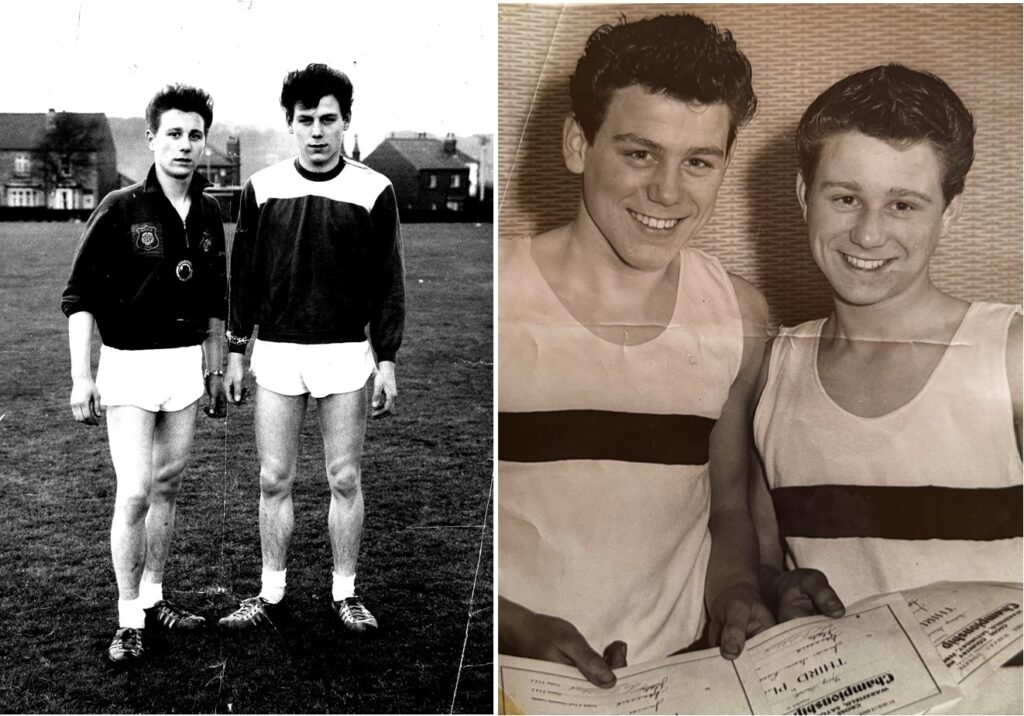

Four of the Stewarts’ six children – Tony, his twin Terry and their older brothers Robert and Michael, were all amateur athletes who ran for Rockingham Harriers. Tony was Yorkshire champion in the one-mile race at 15, Terry was cross country champion, and Bob and Tony won the Grenoside Chase in successive years in 1958 and ’59.

“We were the only family in the village who wore tracksuits. We must have looked like Martians. Athletics and being active were huge parts of my childhood. I had these metal roller skates that I never took off. I was like a baby gazelle when I didn’t have them on,” Tony says.

However, with a father that encouraged his children to learn a trade, Tony went on to become an apprentice electrician with the National Coal Board after leaving school.

His father, Cyril, came from a big working-class family and was one of 11 children. Cyril worked as a manager at a moulding shop in Chapeltown, but he’d been a petty officer in the Royal Navy, sailing around the world twice, before becoming a chief gunner during the war.

“We had some lovely Sunday breakfasts. Mum would cook bacon and eggs and Dad would tell us how he won the war.”

At 18, Tony and his family moved from their quiet and idyllic life in High Green to the grimy streets of Kelham Island when his parents decided to buy the Ship Inn, one of Sheffield’s oldest pubs.

“That was a rude awakening. We moved from a small village with three bobbies who knew all our names to what was then a rough area full of gangsters. Dad never swore and would reprimand anyone he heard swearing. Within six months he’d got the full respect of these gangsters who would tell people not to swear in front of Cyril.”

Cyril and his wife Kathleen worked seven days a week, 365 days a year at the pub, helped by their brood of six kids who slotted shifts behind the bar in around their own jobs.

Having finished his apprenticeship and worked on numerous jobs, including the Royal Hallamshire Hospital construction, at 23 Tony decided to break the circuit and set up his own electrical supplies business.

He had two shops, one in Sheffield and one in Rotherham, which he renamed No Entry Electrical Supplies in the 1970s after a spate of burglaries and increasing requests from customers for burglar alarms.

Then, after ten years, a chance meeting with a German salesman sparked an internationally successful business idea.

“I got a call from a guy in Munich who said he’d seen in the directory that we sold burglar alarms and security devices – could he come and see me? He pulled up at the Sheffield shop at 6:30 one night in an Audi Quattro and showed me this little sensor device, no bigger than a cigarette packet, that he wanted me to sell and distribute.

“He gave me a demo and a bell went off like an alarm when motion was detected. I thought that was a waste. Most people get burgled at two or three in the morning, so surely it was more useful if it could turn the lights on?”

Tony turned down the German man’s offer, but it got the cogs whirring. He went away and designed his own luminaire sensor – the first of its kind in the world. But the draw back was that he’d invented a Black and Decker style product but, by his own admission, his company was like a corner shop.

He needed to look at different ways of operating, so off he went to see the bank manager with a plea for a £40,000 loan.

“I think he nearly fell of his chair. He told me I could have it in a couple of weeks. But this was Monday morning and I needed it by Friday.”

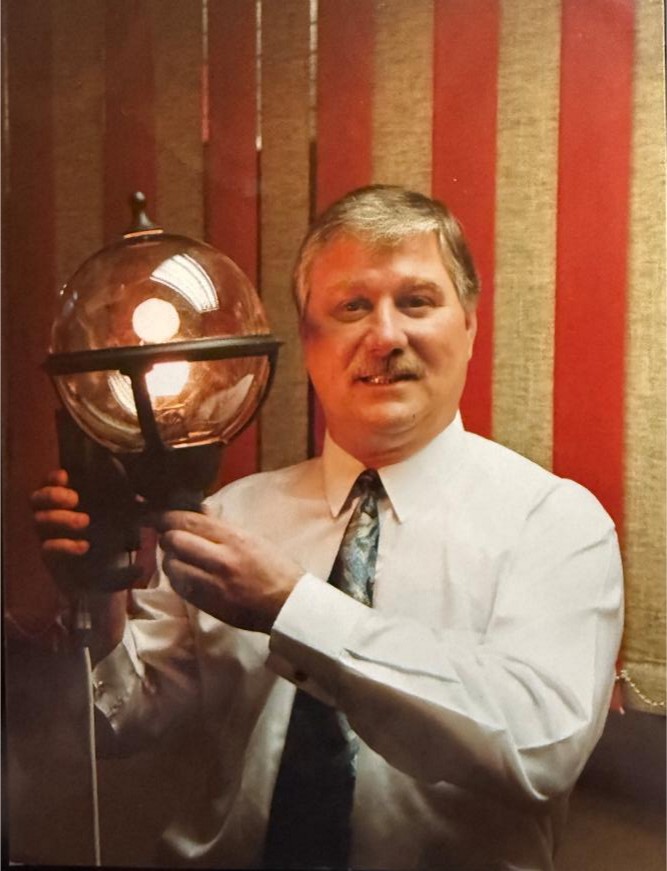

Tony wanted a manufacturer to make his luminaire locally and approached around a dozen firms in South Yorkshire, but nobody could do it. As the saying goes, if you want something doing – do it yourself. And so, ASD Lighting was born in November 1982.

He tasked his small team of six YTS lads in the Sheffield shop with making the sensor in the small upstairs workshop. However, demand was so great that Tony quickly needed to open a factory. Operations moved to a 1,000-square-foot factory on the old Eastwood Trading Estate off Fitzwilliam Road and this soon trebled in size in 18 months.

“It was an horrendous learning curve, and we were borrowing money like you wouldn’t believe, but I knew I had a moonrock product. I remember driving away from our first biggest deal, a half-a-million-pound order from a supermarket in Texas. I was trying to keep my cool walking away with the contract in my hand but as soon as I got in the car, the sunroof was down, and I was shouting with joy.”

With manufacturing getting off the ground, Tony turned his attention to building on the sales momentum – but he had no sales team. Instead, he opted to outsource sales to an established company in Leeds.

“They were sold on the product when the light came on automatically when they walked into my office.”

Tony gave them exclusivity for two years which allowed him to recruit his own team of salespeople ready for when that contract ended.

As turnover quickly reached £1 million, ASD Lighting was rapidly outgrowing its Eastwood home. This conveniently came at a time when Rotherham Council were building the enterprise zone on the old chemical works at Barbot Hall near Greasbrough.

There was one remaining 10,000-square-foot unit available and Tony was one of ten enquirers, but with job creation one of the requirements, ASD ticked all the boxes.

Over the last 40 years, ASD Lighting has doubled the size of its footprint with three factories and a workforce of over 200 staff.

They have substantially grown their product range to now manufacture everything from domestic luminaire and security cameras to app-controlled covert street lighting with face recognition and heat mapping – with everything still made here in Rotherham.

Their products can be found across the globe, from airports and railway stations, to schools and hospitals, and car parks and council street lighting.

That idea lit in his small Sheffield shop by an Audi-driving German has taken Tony across the world, meeting foreign dignitaries, presidents and prime ministers.

But perhaps the most dominant impact of his enterprise is that it put his name in the hat to help save the Millers.

In 2008, Tony was one of six businesspeople invited by Rotherham Council to a meeting at the town hall to discuss the future of Rotherham United after the club fell into administration for a second time.

“There wasn’t a cat in hell’s chance I was going to take over the club, but I agreed to have a look at the state of things. I told the others it would be wise to look at the accounts before any of them put their hand in their pocket.

“I viewed it as commercial business not leisure. It’s not just about the excitement of football. A club, like any business, needs a strong engine room.”

Tony says he looked at three factors: income from season tickets and retail; fixed costs; and running costs. The club was in dire straits. It wasn’t doing well on sales, neither was it supplementing the cost of players. Money was going out faster than it was coming in.

He knew then that someone had to step in to sort the mess out – and so he ate his words and bought the football club.

First on the agenda was Millmoor. Tony went to see the late Ken Booth, the club’s previous owner who still ran the stadium, but Booth didn’t want to implement Tony’s plans or vision.

Never one to dilly-dally, Tony pressed go on Plan B: Don Valley Stadium over the border in Sheffield.

“People said ‘Who’s this Charlie from Sheffield that’s bought a club that’s gone bust twice in 18 months and now wants to move them out of the town and into Sheffield? There was a running joke that you’d need your binoculars to watch Rotherham at home. But we had aspirations and we needed to move forward.”

The football league granted Tony permission to move to Don Valley for four seasons – backed by a £750,000 bond. The ticket office and club shop relocated to ASD’s site on Barbot Hall, and the Millers had a good four years over at Attercliffe, with two cup runs and their first ever play off final in 2010 under Ronnie Moore.

But the clock was ticking on moving back home. If they weren’t back in Rotherham for the start of the 2012/13 season, Tony would be hit with a £2 million fine.

He worked with Rotherham Council to find a site for a new stadium. Land off Centenary Way, which had been earmarked for a new library, was too small at just seven acres. But Tony was told there was a further seven acres of private land adjoining it.

“I had to be quick because, if others got wind of it, I’d have been held ransom. After we bought both bits of land, we only had about a year to build the stadium. This was after the financial crisis in 2008 when the economy was in decline. Contractors were eager to get work so they didn’t have to lay off staff, and most were willing to do it at net cost.”

Over 60 contractors applied for the stadium construction, and the job ultimately went to Leeds-based GMI. At the last minute, Tony added a second tier to the design to increase capacity and scope for hospitality. It was a massive gamble, set to come in at around £20 million – Tony being the majority funder with an injection of £6.7m.

Ground was broken in June 2011 and, following a 50-week build, everything was ready for the first match of the season in July 2012.

“I was like a foreman, on site every day. I touched nearly every brick laid and was up and down the scaffolding. But there was a lot at stake if we didn’t get it finished on time.

“The attention to detail was meticulous. We checked every cubbyhole for things like lighting and plug sockets. I wouldn’t have taken a single pound off what we spent or changed anything about it. Just like designing a product, people have got to like it to buy it.

“You’ll never take away the nostalgia of Millmoor and people still talk about the good times they had there. But visiting clubs would get off the coach, see the state of the away end changing rooms, then get straight back on the bus to use the showers at somewhere like Wakefield.

“I always say that if you set a table, make sure you’ve got a clean tablecloth. Whatever you bring to the table after that will be lifted. This stadium will be here long after I’ve gone and that will be part of my legacy.”

New York Stadium has shown what you can do with a stadium of that size. It’s reconnected the club with the town and restored civic pride.

As well as revitalised facilities, the start of the New York era activated an invigorated mentality and craving for success throughout the club.

Feeding that hunger was Steve Evans, whose management saw the Millers claim back-to-back promotions in their first two seasons at NYS, catapulting them from League Two to the Championship.

“Most Rotherham fans will have a memory of Steve nearly losing his trousers at Wembley when we played Leighton Orient in the 2014 play-off final. He set the bar for us as a manager. I’ve never professed to knowing much about football, I leave that to my son, but I’d seen Steve at fourth tier Crawley Town who were giant killers in the FA Cup.”

Evans left Crawley for Rotherham in 2012 ahead of the club’s first season at New York Stadium. With him, he brought a new style of management, a revolving door of new players, and a buzz of excitement amongst fans.

There’s been a succession of managers since Evans left in 2015, including Paul Warne who was in charge during their best season on record in 2022 when they were promoted back to the Championship and won the EFL Trophy at Wembley.

For the centenary season, Matt Hamshaw is in the driving seat, joined by Richard Wood and Dale Tongue who are all no strangers to the club.

“Managers come and go and that’s just the way of the world. They follow the money. Matt is smooth. He’s been part of the club for twelve years and has a good mentality. It’s a mystery when you sign a manager you don’t know, and I don’t like mysteries.”

He admits that it’s been an emotional rollercoaster in recent years, which saw him almost walk away altogether in 2024 after being absent from many home games.

Football is a volatile game to be in, and overspending can collapse a club, especially when you’re trying to compete against clubs with celebrity owners, foreign billions, and conglomerate cash.

With a workforce of around 250 staff at Rotherham United, Tony has a fiscal responsibility to build a sustainable club rather than chasing glory at the club’s long-term expense.

“It’s the first time in a few years where we’ve not gone straight back up to the Championship after being relegated, but it feels comfortable now after 18 months of discomfort. Of course you get used to being in that higher league, but our three-year strategy is focused on bringing in young players rather than a revolving door like we’ve had previously. That’s no good as you have to start again when they leave.”

Tony remains a rarity in modern football, a local businessman done good. But he’s the first to admit he’s not been a lone ranger on this crazy journey. Every decision about finance, structure or new initiatives, he’s made with a team of people he classes as family, people he trusts, people who work with him – not for him.

So, what’s next for him personally? He’s got a big birthday coming up this October – but there probably won’t be a surprise party in The 1925 Club with red and white balloons as he’s already told us he hates mysteries!

Will he ever retire? Who knows. His son Richard is vice-chair and in good stead to lead the club should his dad ever take more of a back seat and swap football clubs for golf clubs. Teenage grandson Thomas is a keen golfer who wants to become better than Tiger Woods, so Grandad Tony has even more excuse to get out on the green.

What if someone offered to buy the club tomorrow? Would he walk away for the right price? Maybe.

But one thing’s for sure, he’ll never lose his love for Rotherham: a town that adopted him as their own, a town where he’s spent 45 years of his working life, a town where he’s been given the Freedom of the borough, and a town where he met his beloved late wife, Joan.

She was a Rotherham lass, from Thorpe Hesley, and the pair met at a dance at The Grapes in Dalton. They married in 1971 at Sheffield Cathedral and were together for many happy years, raising their only son, having three grandchildren, and building a beautiful home together off Moorgate.

Sadly, Joan passed away in 2019, just two weeks before Tony was presented with an OBE by then Prince Charles at Buckingham Palace for services to business and the community in Rotherham.

As Rotherham United celebrates 100 years of football in 2025, what would the founder members from 1925 think?

They’d no doubt doff their caps to a man whose legacy will be not just in trophies or balance sheets, but in the hearts of a town that found its soul again through the game he refused to let die.