At just 16, life wasn’t so sweet for Victoria Nixon. The world around her was crumbling as quickly as the chocolate bar she would one day go on to advertise. But she was not the type of girl to be consumed by the flakes of grief that were settling around her.

Barely out of school, Victoria had already lost her father to suicide which forced her mother to sell their family home in Barnsley. Her older brother was then admitted to a psychiatric hospital after attempting to fatally stab himself at university.

She knew more about loss than life.

But as they say, the flower that blooms in adversity is often the most beautiful of all and from the seeds of tragedy did a flourishing, ambitious and successful woman grow.

Armed with a teenage dream, this head-strong, unruly and utterly striking young lass from Barnsley set out on an adventure to find freedom, carving out a lucrative modelling career along the way.

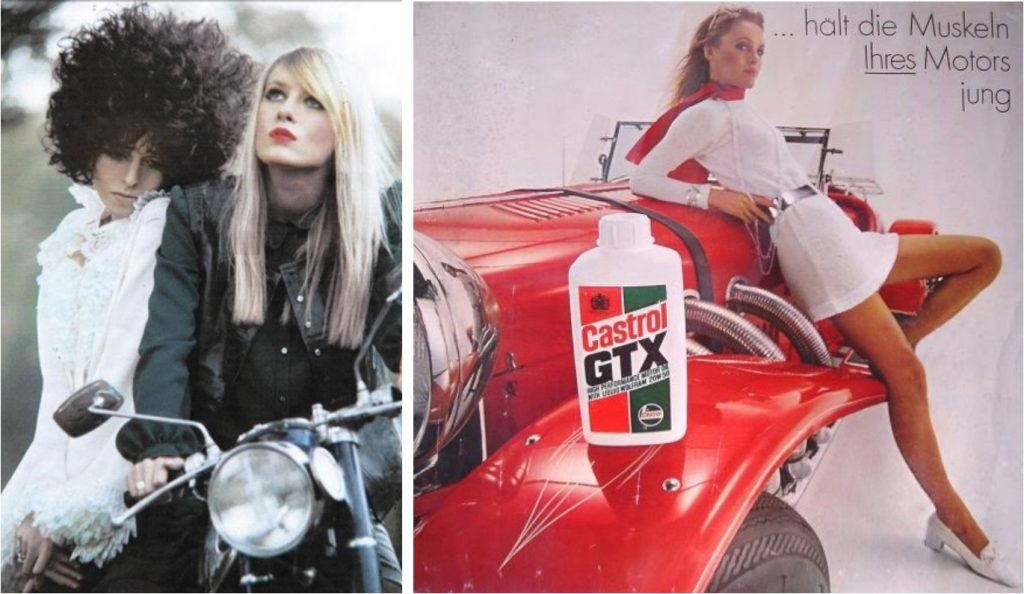

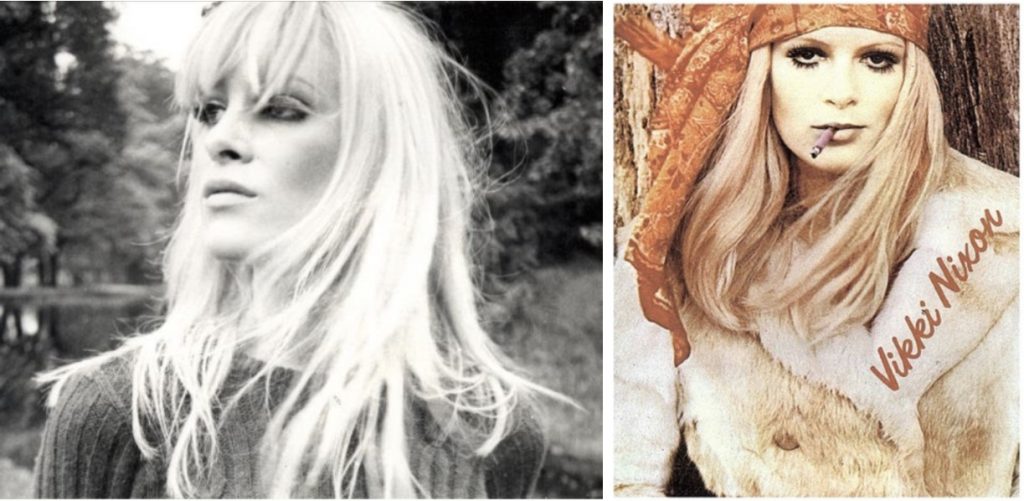

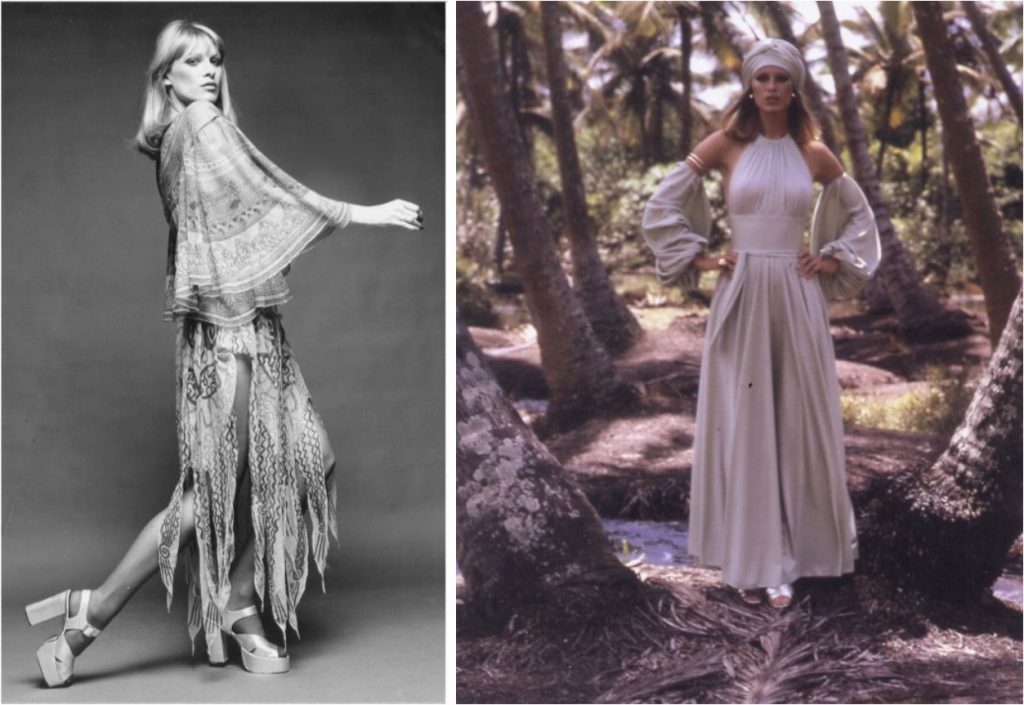

During her decade-long heyday in the ‘60s and ‘70s, Victoria’s nonconformist look, with her wild hair, strong cheekbones and expressive eyes that hid a painful past, preserved her a place on the pages of glossy fashion magazines.

Her signature brooding look appeared in the likes of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Glamour and Elle. Her lithe figure advertised everything from raincoats to motor oil and even a Sheffield-made steel dress. She modelled space age fashion for the Apollo 11 moon landing’s live coverage and was Top of the Pops’ first promo girl.

Over the years she would go on to talk cars with the Shah of Iran while posing in the Alps, have the Beach Boys sing happy birthday at her 21st bash in London, take a tour of Andy Warhol’s New York factory by the man himself, and have dinner with Salvador Dali and his wife in Spain. None of whom had ever heard of, never mind visited, Barnsley.

Her paid-for smile was a ticket to ride, swapping Fray Bentos pies in Yorkshire for pistachio macaroons in Paris. But while she was drawn to those days in the sun, a cloud of sorrow swiftly followed – leaving little pieces of her heart and former life behind in each new city.

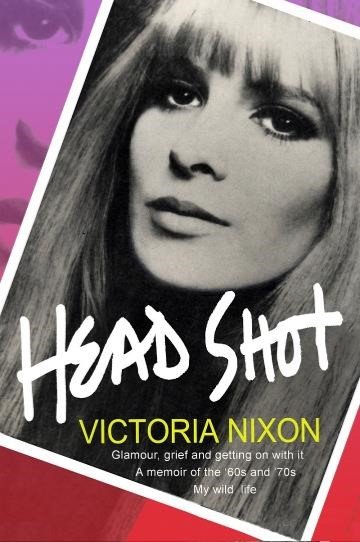

After more than 50 years of eluding those sad events, Victoria has written a memoir to confront the traumatic times she’d locked away – and to inform, help, change, and possibly save other lives.

Head Shot is a warts-and-all tale about the extreme highs and lows Victoria has faced in life, with a little bit of sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll thrown in for good measure. The soul-bearing journey follows her from a teenage muse through her rocky relationships until finally finding peace away from the camera flash.

Born in Barnsley in 1948, Victoria had a respectable upbringing. Her parents, Arthur and Patricia, both from well-to-do backgrounds, had met during the war when he was an army major and she voluntarily drove ambulances.

Her maternal great-grandfather had cleaned up after inventing the scouring pad and the family lived at Oakwood Hall off Moorgate in Rotherham. Patricia boarded at Cheltenham Ladies’ College and a Swiss finishing school.

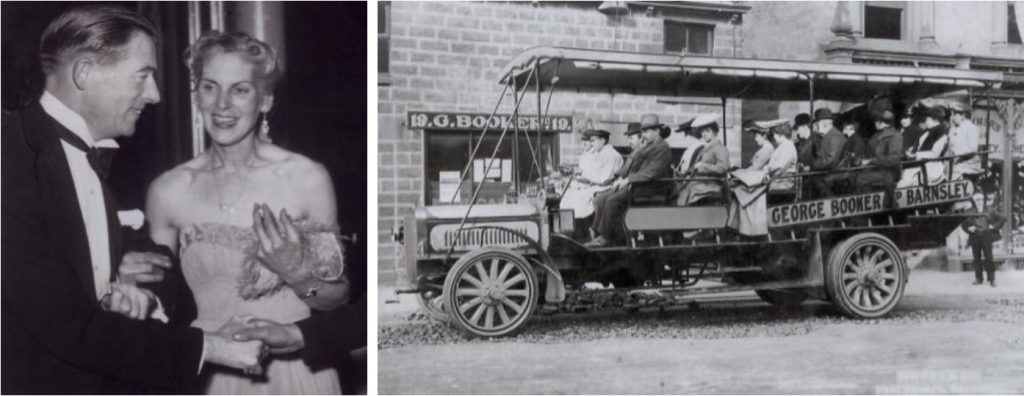

Arthur’s family introduced transport to Barnsley, first carrying Royal Mail by horse and cart and later launching the first motorised bus. His mum Agatha’s family owned pubs including the old Shakespeare Hotel.

Although not directly part of Barnsley’s true elite who grew up overlooking their dad’s workplace colliery, the Nixon-Bookers were highly active in local Barnsley life.

Arthur, an engineer, took over the reins of the family car dealership and managed two sites across Barnsley town centre. Patricia stayed home but was never the mumsy type, choosing interiors that required little cleaning and dinners that required little cooking.

Together, they lived an active social life with cocktail parties the norm at their detached house just off Huddersfield Road.

“Despite her Bloomsbury Set-style upbringing, Mum was one of the most down to earth people. Everyone adored her. Men loved her brains and humour, women loved her loyalty as a friend and both loved that she was never the flirtatious type,” Victoria says.

Growing up with older brother Nick, Victoria’s childhood was spent outdoors climbing trees. When Nick went to boarding school, Victoria bonded with Granny Aggie who lived with them.

Victoria has always steered away from the obvious or predictable – when she asked for a younger sibling, she was thrilled when her father bought her a 12-inch alligator. She shied away from private schooling, the first for generations to do so, and instead attended Barnsley Girls’ High School.

Summers were spent at Oxford with her dad’s brother and his family, which is where a 13-year-old Victoria was when she learnt of her father’s death.

Nick’s new Mini was on the drive when she got there which Victoria thought strange as he should have been studying fine art at Durham University.

He had been sent to deliver the bad news. Arthur was dead.

Nick had discovered his unresponsive body at the family garage. Carbon monoxide poisoning. At just 19, Nick watched their father pass away in hospital.

“Dad had no previous history of mental health. There was no indication he’d take his own life, he was the happiest man in the world. The coroner stated he’d had a ‘fit of depression.’

“To this day it hurts so much that Dad chose death as the only option to his financial woes. He’d had worries at work brought on by the Suez Oil Crisis but had placed an order of new Minis which he thought would change his fortunes. Sadly, they’d been under-priced and Dad would only make £15 on a £500 car.”

Arthur’s death was never discussed, his possessions removed by the time Victoria got home. His passing affected the whole family; Arthur’s brother, who had invested in the family company, cut all ties and Victoria never saw her cousins again. Granny Aggie never came back from Oxford.

Back here in Barnsley, many folks didn’t know how to react to the news and avoided the family; they weren’t accustomed to people taking their own lives.

For Victoria, life had to go on. She threw herself into sport for a short while, having been inspired by Barnsley’s shining sprinter, Dorothy Hyman.

Then she found boys and her studies took a back seat while she was upfront canoodling. But she was far too young to settle down with the first boy she loved.

“I wanted to see the world not marry the first guy I went out with – how could I be sure he was the right one when he was the only one?”

While watching Manfred Mann at Peter Stringfellow’s Mojo club in Sheffield, lead singer Paul Jones first suggested the idea of modelling, not knowing Victoria was still at school. But it wasn’t until a few years later that the idea grew long legs and gained momentum.

After Arthur’s insurance policy failed to pay out, Patricia was forced to sell the family home and sought employment, first at a jewellers’ and then as a bursar at Bretton Hall College. Not long after, her brother Nick began to have serious mental health problems whilst a student at university.

Perhaps it was time for Victoria to concentrate on her own future.

Paul Jones’ modelling suggestion was researched by Patricia who concluded that London’s Lucie Clayton Academy in Bond Street was Britain’s leading model agency, but they were very choosy about who they accepted, with previous alumni including Jean Shrimpton and Fiona Campbell-Walker.

She worked overtime to pay for Victoria’s train fare to London and the month-long course fee of 28 guineas, but on one condition – she also had to do a secretarial course as a back-up plan.

“My mum knew how to handle every situation and she gave wise, well-balanced advice. She was never victim-esque; she could have said to me, ‘Stay here and care for me, darling.’ But instead she packed me off to see the world and have a good time. ‘Your home is always here to come back to,’ she’d say.”

Instead of taking her A-Levels, Victoria headed to London to join the course which was more like a finishing school for posh girls looking to be debutantes. This Barnsley lass wasn’t like the rest – she wanted financial independence, not to be a kept woman.

“Why marry for money when you could earn enough yourself?”

When Vidal Sassoon offered her his signature bobbed haircut for free, Victoria turned it down.

“Why would I want to look the same as everyone else?”

After a month of balancing books on her head and learning how to not flash her knickers as she exited a car, the passing out parade loomed. But Victoria’s cool vibe backfired. She failed magnificently, the only girl in Lucie Clayton history to fail – ever.

“Everyone else chose these pastel two-piece skirt suits and dainty heels. I wasn’t into that. Biba gifted me this floaty black dress and I bought some purple suede boots from Russell and Bromley which I had to walk down a catwalk in. They said you should never wear black in the day, my hair was too wild, I didn’t wear enough makeup and I walked like a carthorse.”

The ‘back-up plan’ was now ‘the necessary plan’ and Victoria became an accounts typist at a Mayfair advertising agency.

“Mum wasn’t fazed by anything. She just said, ‘Never mind darling, something else will come your way.’”

And sure enough, it did.

While at work, she literally bumped into fashion photographer, Mike Berkofsky, who was doing a shoot for Alice Pollock’s Quorum boutique. He compared her to Bonnie and Clyde star Faye Dunaway and asked if she’d ever thought of modelling, suggesting she contact Askew Model Agency.

A name change to Vikki and a few ‘Don’t mess with me’ poses later she was booked to launch YSL’s revolutionary Le Smoking trouser suit.

Her career then went up another notch when she was spotted by controversial Vogue photographer, Helmut Newton, while window shopping on Bond Street. She was booked for a shoot almost immediately and was excited to see Newton’s provocative style in action – but to her dismay it was more school uniform than sensual goddess.

From a place in British Vogue did an international career follow. Vikki was the first Brit to be offered work for Riccardo Gray’s new Milan agency, earning around £9,000 in today’s money for a few days’ work around Italy.

“But I lost it all at customs after stashing endless notes in my pants and bra.”

Over the next ten years, Vikki Nixon travelled the width and breadth of the earth armed with her passport, tear-sheets and trusty kit.

“Despite what people might presume about modelling, it was pretty hard work back then. Your agent would call and say a ticket was waiting at the airport for a job in this country or that. My final shoot was in Sri Lanka and I’d never heard of it but presumed it was in Italy – 14 hours later I finally got off the plane.

“There was no stylist on location then; we had to do our own makeup and hair, carrying endless products, wigs, shoes and underwear with us. I’ve still got the shoulders to show for it.”

Vikki’s era was the time when meaning triumphed narcissism; it didn’t matter what you wore but who you were. Models weren’t media personalities, their names rarely known, and they never worried about their weight.

When named the Daily Mail’s Face of ’68, Vikki considered it no big deal. She didn’t want her youthful face to define her life.

In 1971, she signed to Ford Models in New York, the best agency in the world. Vikki’s rollercoaster life had hit a peak – but a pit was fast approaching.

Nick, now a furniture designer and estranged from his wife and two children, came to stay at her Manhattan apartment having been invited by Richard Avedon who wanted to photograph one of his pieces.

While she went home to England for Christmas, Nick, perhaps held by the burden of his dad’s death, died from a combination of wine and pills aged just 30. His sister would never know if it was intentional or just another cry for help that sadly went wrong.

The pain of losing not one, but two of the most important men in her life to suicide pours from the words in her book, with a strong message throughout.

“Those who are left behind by suicide carry the pain of those who depart. You need to counterbalance it by enjoying the rest of your own life and not letting tragedy hold you back. I’ve had messages from people who have read the book saying it has changed their outlook on life.”

However, Vikki channelled her grief into rescuing others, often to the detriment of herself, which she also covers in the book with a ‘lessons in life’ chapter looking at how to spot a toxic relationship – something she knows all too well about.

While working in Zurich, Victoria met her first husband whom she presumed was a psychology student; he turned out to be an addict undergoing medical research and would end up in prison for drug offences.

She went on a date with French TV presenter, Olivier Todd, the only man who preferred to discuss current affairs than have one – and the one who got away, she says.

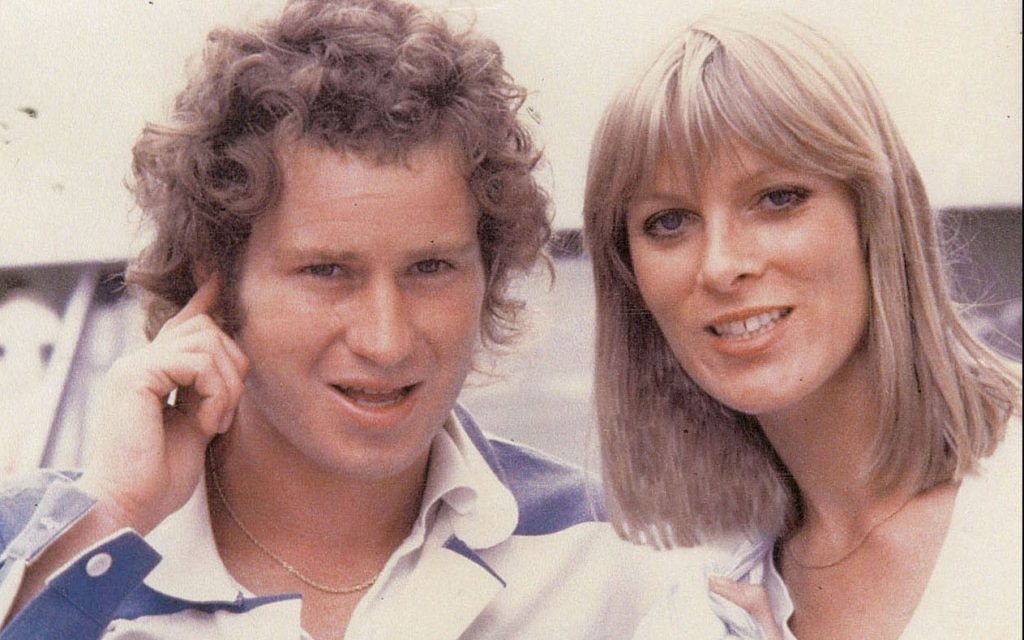

At 25 and wanting a more brain-alert career than the world of modelling, she was introduced to her second husband who worked in advertising and used her for her final ad shoot in a Cadbury’s Flake TV commercial.

After the death of her mother to heart disease aged just 61, the pair moved to Australia where Victoria left modelling behind for new horizons.

“Mum’s death had shattered me. She never had another relationship after Dad and had moved down south to be near me. And now I was in my mid-20s with no family left. But as Mum would say, I needed to buck up and get on with it.

“Banking on your looks is a finite game, I knew I needed to foster qualities that would grow, not fade.”

During the ‘80s, Victoria’s new life down under was primarily spent in advertising after rewriting the script for her husband’s John McEnroe milk commercial. She won script writing awards before going into magazine editing and documentary production.

But like a real-life Don Draper, her second husband had a drink problem and entered rehab 13 times. When their marriage ended, Victoria was approaching 40 with two failed marriages and no children. She moved back to London to find peace.

It came in the form of a delicatessen which she opened in the early ‘90s and attracted customers from miles for her range of continental-style foods and salads. Hugh Grant even became a regular.

An average day would start at 5.30am where Victoria would take fresh produce deliveries from Covent Garden market. She grew her own herbs and used local honey while also juggling VAT and annual accounts records.

The deli was the first in the UK to use eco-friendly packaging such as palm husk containers, acid-free paper bags and biodegradable cutlery.

“It’s always repelled me to see how much stuff is unnecessarily packaged in plastic. I can’t believe that it’s taken this long for the rest of the world to wake up to the global issue.”

Not long after, she also met Mr Right.

“He didn’t call for a year but he said he’d sensed I needed time. We had an instant connection; he’s my best friend and gives me strength. Dad and Nick would have loved Michael because he’s a designer and engineer like them, plus he’s the one looking after me for a change, not the other way around.”

Following approval by fellow Barnsley-er Michael Parkinson, whom she first met in Australia when both were working there in 80s, she and Mr Right first became a couple in 1994 and married 10 years ago. Victoria is step-mum to Michael’s daughter, not wanting to put pressure on the relationship by trying to start her own family in her 40s.

Together, the pair launched a humanitarian aid company in 2005 designing and manufacturing innovative shelter, hygiene and sanitation products which are used in Haiti, Nepal, South America and throughout Africa.

“We’d been living a life of relative luxury together and felt we’d become detached from reality. It was seeing the footage from the Kashmir earthquake that made us want to make a difference, more than just simply donating money to charity. We used funds from the sale of our possessions to start up the company.”

When Victoria finally found the courage to revisit her roots, and first brought Michael to Barnsley for a tour of her old stomping ground, she discovered her father’s showroom in Wellington Street had been pulled down the day before. A welcome reprieve from painful memories.

Today, Victoria is living proof that she is far more than just a vacant stare in a glossy magazine. Her youthful looks as the Face of ’68 remain but it’s her humour, wit, and warmth that radiates through – albeit she has somewhat lost the Yorkshire twang.

“But I’ll never stop being that proud lass from Barnsley, wherever life takes me.”

Head Shot is priced at £16.99 and is available from Amazon