As summer turned to winter, the harsh reality of the strike set in for many.

Their coal reserves were depleting, with many young lads going out scavenging the pit tops for any bits of coal they could find. Many got buried, including two teenage brothers who were killed at Goldthorpe while collecting coal.

Christmas was a depressing time for most. But miners made do, helped by donations from the community.

As funds ran dry and families found it harder and harder to put food on the table, destitute miners started to trickle back to work through picket lines where they were branded ‘scabs’ and sometimes physically assaulted.

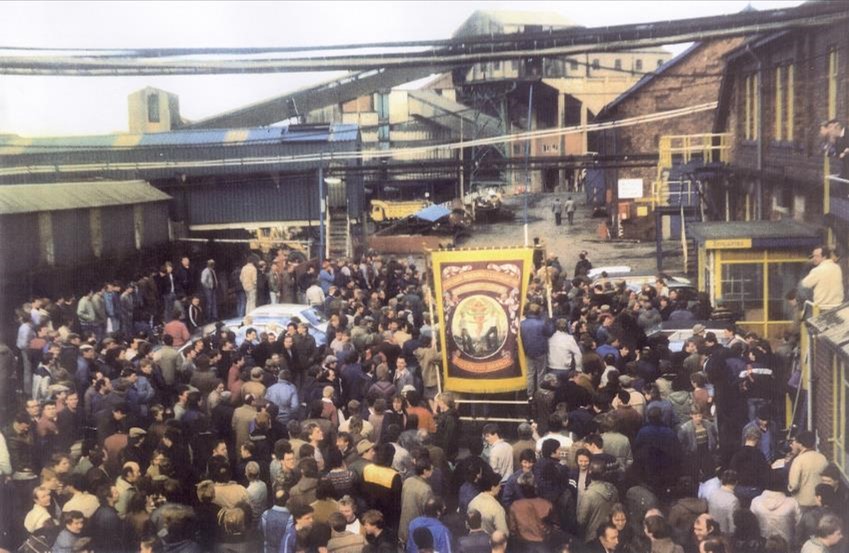

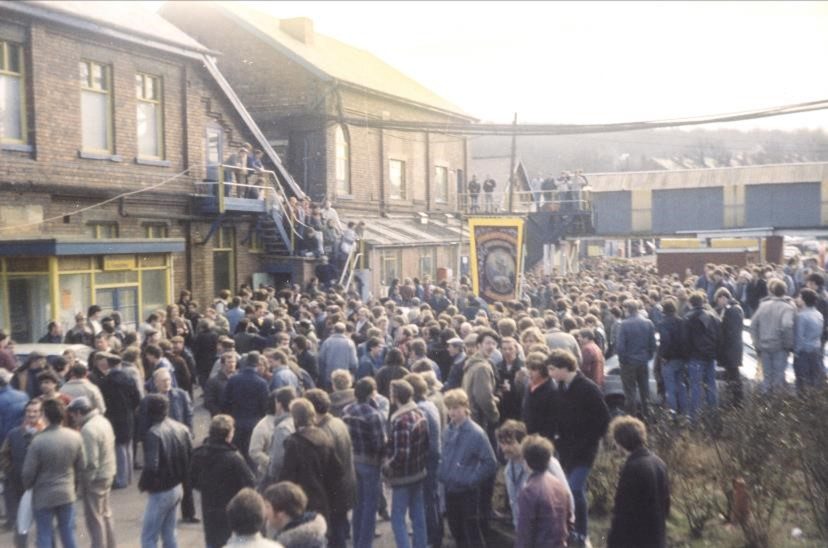

Many believed the strike was over by Christmas. They could see no end to the dispute. But the strike wasn’t officially called off for another three months. The call for going back to work eventually came on 3rd March 1985.

“A lot of the narrative was that the miners were defeated. But they went back to work with their heads held high. They had been fighting for a principle they felt was worth striking for. To keep their jobs going, their communities going. When you took a pit out of a village, you tore the heart out of it and some places still haven’t recovered from that,” says historian Brian Elliott.

Out of the strike came a rebirth in many ways. While many former miners faced unemployment, others went back to college and requalified for new professions. Miners’ wives, in even greater numbers, returned to education and became teachers, social workers or probation officers. The children of mining families, brought up during and after the strike, made the fullest use of the expansion of the university sector.

“There was more emphasis on education after the strike, but those with an education quickly moved out of the area for better job prospects. Pit villages were no longer working areas, they were commuter areas. Developers built houses on old pit sites but people from those villages can’t afford to buy the houses,” says Chris Kitchen.

But so many young lads were bitter after the strike. Theywere born to be a miner – and wanted to be a miner. Because of the strike, there’s a generation who had that opportunity taken away from them. Chris’ younger brother was one of them.

“He was in his last year of school during the strike but rarely went. He was always out picketing instead, fighting for what he thought would be his job. But he never went down the pit. He left school at the wrong time, at the time of strikes and closures, and he always resented that. He never really settled in a job and my mum and dad ended up buying a corner shop for him to run.”

For many who had gone back to work at the collieries, they didn’t stay there for long. Bruce Wilson says Silverwood was never the same after the strike. By 1988, more pits were closing and he was offered redundancy.

“Loads of lads were leaving. I was a loco driver and you couldn’t man up without a guard. I finished in February 1988 with three months wages up front and a redundancy payout of 18 months’ wages, about £10,500.”

While the pits may have closed, the heritage of the mining industry has been preserved in many ways. There are now mining museums, the revival of banner-making for the Durham miners’ gala, and the political struggle continues through the Orgreave Truth and Justice Campaign.

Sylvia Croft and her husband Reg are involved in Silverwood Colliery Heritage Group. They started up before the pandemic, collecting memorabilia from those who worked down the pit. Plates, badges, pit checks, miners’ lamps. Those sorts of things. Last year they ran a pop-up exhibition at Clifton Park Museum, which stemmed the idea of the 40th anniversary event there.

The group continues to ensure that the area’s mining heritage isn’t lost. At Christmas, they held an event where they lit up the old pit wheel for a service to remember the miners who died in 2023. They’re also looking at digitising their collection to create a virtual museum that people can access.

And Sylvia makes mining themed mugs, badges and t-shirts that she sells to customers across the globe, with profits donated to mining charities.