This March marks the 40th anniversary since the start of the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike, the longest, most bitter industrial dispute in British history.

A battle of wills where neither side would back down. A battle that nobody thought would last as long as it did. A battle that has since shaped the South Yorkshire we know today.

Since being nationalised in 1947, the once booming coal industry had burnt out at a record rate. Almost 1,000 pits had been whittled down to just 173 in the space of 35 years.

Then the National Coal Board announced another set of proposed closures, putting another 20 pits and 20,000 jobs in the firing line.

At risk of losing their jobs, communities and whole way of life, miners fought back using the best weapon they had – withdrawing their labour.

The strike began here in South Yorkshire with a walkout at Cortonwood Colliery on 6th March 1984. What followed was 12 months of tension, anger and struggle.

But it was also a time of alliance. People came together in defence of their communities and the basic rights to work and to survive.

And for better or worse, it’s undeniable that the nation has never been the same again.

If you’re expecting to read the usual Scargill vs Thatcher debate, then it’s probably best you skip a few pages. Aroundtown is a magazine for the community, so our tribute tells the stories of those at the heart of the strike.

We’d like to thank everyone who contributed to this feature. The former miners we spoke to who shared their memories and photographs. The people who are organising events and exhibitions to commemorate the strike. We’ve laughed at some stories, been totally shocked at others.

I felt an overwhelming sense of pressure to get this article right. But that’s only because I felt duty bound to do justice to those whose lives it did upend, and to keep the story going for the post-strike generation.

People like me who were born in the decade after the strike. Who never experienced the motherly nature of the pit community. Whose first knowledge of the strike came from watching Billy Elliott. Who might question why people still haven’t gotten over it 40 years later.

But they never will.

Whatever your own opinion of the strike, it’s hard not to empathise with miners for what they endured during that long year.

We’ve seen a resurgence in industrial action in recent years, with everyone from train drivers and healthcare workers to university lecturers and food delivery drivers walking out for better rights and pay. But no such plight compares to what happened in 1984-85 in size, duration or impact.

How did miners survive without pay for a year? There were no welfare payments for striking miners. Some mortgages were frozen. Families received child support payments for the kids. But it was left for communities and good-natured non-miners to ensure families were fed.

As disposable income of families dropped significantly, how did businesses who relied on their trade survive?

From an outside perspective, you can see why some decided to return to work. They had their own reasons, from ill health to mounting debt. During my research, I read a story about a miner who had diabetes. He couldn’t afford the medication or special diet he needed, and he’d started to lose his sight. He went back to work to save his vision for a few more years.

The strike was never about more money. It hadn’t been about better working conditions or health and safety. It had nothing to do with material gain. It was simply a fight for miners’ futures.

The pit was like the sun and the rest of the community orbited around it.

It employed around 2,000 people from these small villages. Those same families socialised together at the miners’ welfare clubs, or played football or cricket together on the colliery recreation ground. Their kids all went to school together. And with each new generation the cycle began again.

People make the mistake of thinking all miners were underground workers with a shovel and a pick. But there were fitters, plumbers, electricians, surveyors. People were employed as loco drivers, dust and noise officers, pithead baths attendants, canteen staff, accountants and HR officers. The NCB were good trainers, their apprenticeships were high quality and miners could take those skills into other jobs.

Older or infirm miners were always looked after. They’d worked their way up through the years but often had ill health or industrial diseases. But jobs would be tailored to them so they could manage instead of being thrown on the scrap heap.

So, that’s why the fight waged on.

“It wasn’t a glamorous job that we were fighting for, so it makes you wonder what we were doing,” says Chris Kitchen, general secretary of the NUM.

His family had witnessed first-hand how dangerous the life of a miner could be. His grandfather was killed at Combs Colliery in Dewsbury when he was just 36. It was just before Christmas and he’d been working overtime for a bit of extra money for his family. He left behind three children, including Chris’ dad Ron who was ten at the time.

Despite the tragedy, it didn’t stop Ron nor Chris from going down the pit.

Chris was just 17 when the strike began in March 1984. He’d started at Wheldale Colliery in Castleford in July 1982, a month after his 16th birthday. His dad Ron and uncle Malcolm were also striking miners from Thornhill Colliery in Dewsbury.

“As a young lad, it started off as a bit of fun being off work. We respected the older miners; they knew what they were doing so we followed them out. The weather got better and we had a decent summer, so what was there to rush back for?”

Chris has been the general secretary of the NUM since 2007. After the strike, he was transferred to Kellingley Colliery where he stayed for 20 years before being elected to lead the NUM.

NUM Headquarters Barnsley

He gave us a tour of their headquarters in Barnsley which was the nerve centre of the Yorkshire strike effort.

But today its presence on Huddersfield Road is ambiguous, with people mistaking the grand grade II listed building for a crematorium.

It’s been in the town since the 1800s when the South Yorkshire Mining Federation bought the land to build two houses with offices in between.

It became the headquarters for the Yorkshire Miners’ Association in 1881 after the merger between South and West Yorkshire’s mining federations. The YMA became part of the National Union of Mineworkers in 1947 when the industry was nationalised.

After the strike, the NUM’s headquarters moved from London to Sheffield. But when this closed in 1992, Barnsley became the new HQ.

The main hall, or council chamber, was added in 1912. With stained glass windows, art deco panelling and a beautiful ornate ceiling, it’s chapel like in its interior.

It was used for monthly delegates meetings. But there were never enough chairs for all delegates in the area. One chair was said to represent 1,000 jobs. During the strike, miners would fall back to the NUM office to collect their picketing money, food hampers or vouchers.

These days, the seats are used by visiting school children or when the site is open to former miners as a warm space.

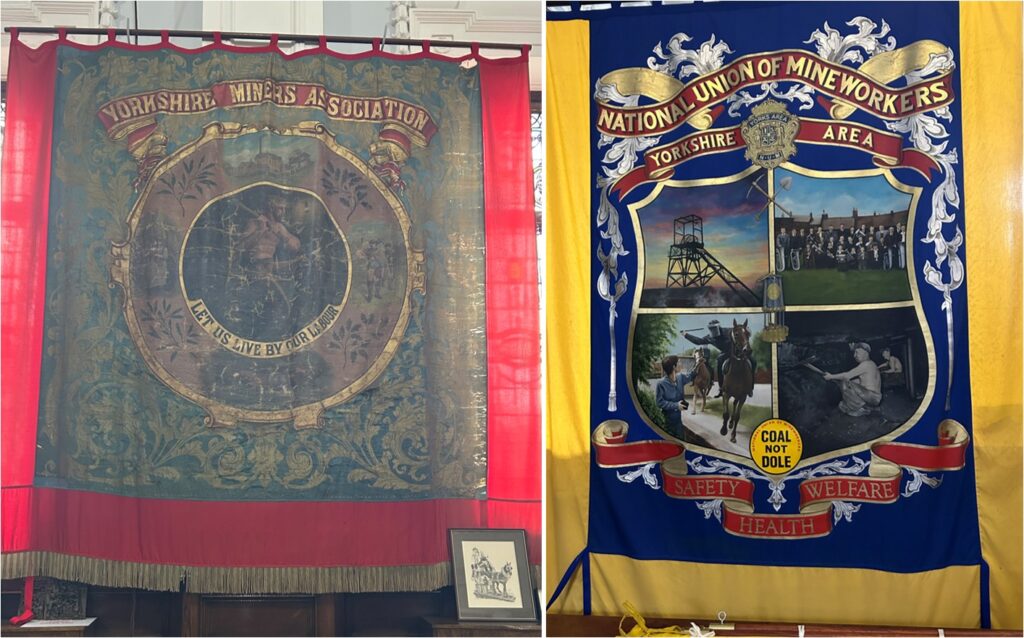

The chamber is filled with pit banners of varying ages, from the oldest being a banner from Lofthouse in 1890, to the most recent one commissioned in 2008 to represent the whole Yorkshire area.

“The Lofthouse banner technically shouldn’t exist – it’s hanging on by a thread. Banners don’t weather well; they’re oil paintings so they start to crack over time,” Chris says.

There are also tributes to some of the more tragic moments in Yorkshire’s mining history, including the Oaks disaster of 1866. Multiple explosions at Barnsley’s Oaks Colliery killed 361 people making it the biggest, most devastating mining disaster in English history.

There’s a framed memorial listing all those killed, as well as the original cast for Graham Ibbeson’s NUM sculpture – the bronze statue of which stands outside the building.

Through another room is the NUM’s museum of sorts featuring archive material. A lot of it went to Warwick University but what remains has been organised by archivist Paul Darlow. Paul, a former Wolley and Houghton Main miner, left the mining industry in 1990, went on to study history at university and became a teacher.

“I saw the state of the archives and knew they needed saving,” he says.

As well as written material, the collection includes pit badges, brass checks, and other collectables like mugs and plates. Other memorabilia relates to the strike, with a t-shirt signed by Scargill, a jacket worn by a miner killed during strike action, and Chris’ dad’s old picket hat covered in badges.