This year marks 100 years since the FA Cup final was first held at the original Wembley Stadium.

And it also marks 100 years since one of the most catastrophic and irredeemable betrayals made in footballing history.

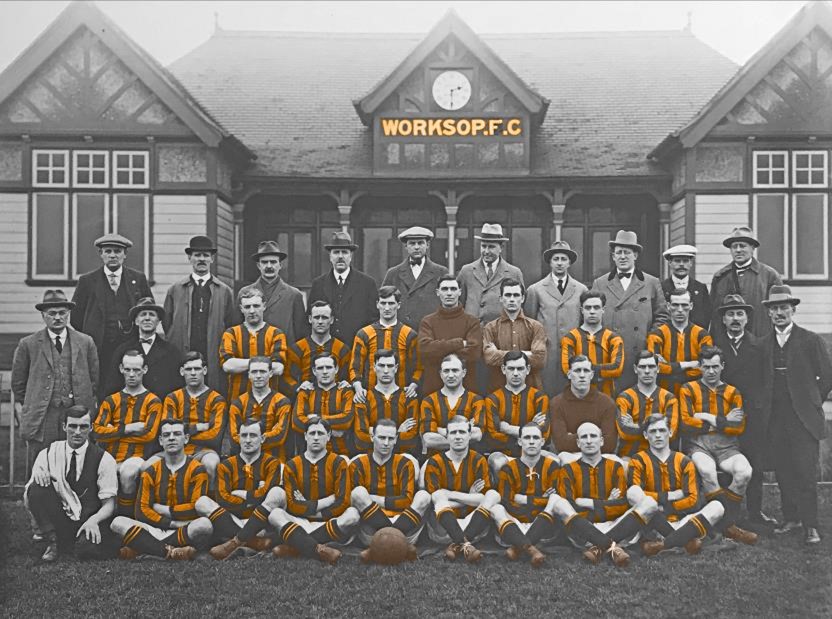

Non-league Worksop Town FC sent shockwaves through the sporting world when they drew 0-0 during the first round of the 1922/23 FA Cup against Tottenham Hotspur, one of the most glamorous teams in the country.

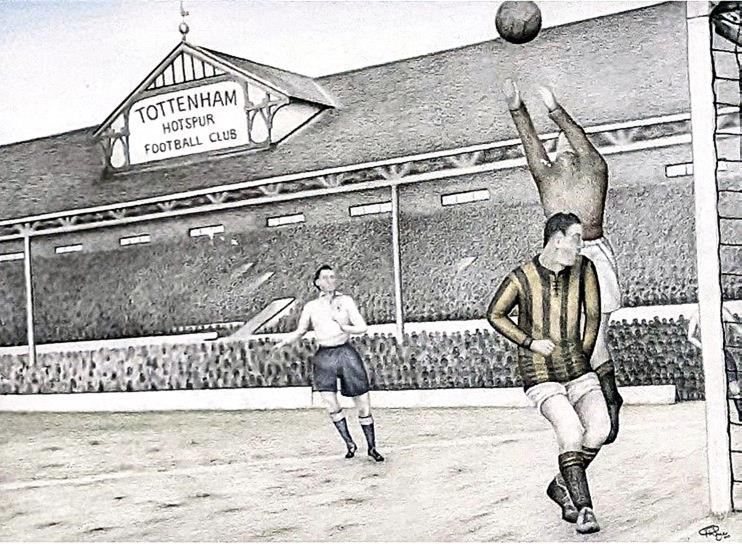

Spurs had been humiliated on home turf by a bunch of amateur footballers who’d travelled to the capital for the very first time from a northern mining village nobody had ever heard of.

The champions of the south had wrongly presumed that victory would be easy. But Worksop were champions of the Midland league, used to playing the reserve teams of some of the strongest clubs in the country.

It was the biggest game in Worksop’s history, starting as equals against legends of the English game like Arthur Grimsdell, Fanny Walden and Jimmy Dimmock; they had nothing to lose and everything to gain. The Worksop squad, the majority of whom had come straight off the back of a shift down the pit, put up a strong fight to make it a goalless draw.

Fearful of another mauling by the Tigers, Spurs didn’t want to leave anything to chance. They were so desperate to be the first London team to play at the inaugural Wembley final that their directors deployed dirty tactics on Worksop to ensure their run of success.

Bribes, backhanders, and a boozy pre-game night put paid to what could have been a once in a lifetime chance for Worksop to reserve their place in the history books as giant killers.

The directors at Tottenham convinced the Worksop sub-committee to stay in London and have the replay at White Hart Lane instead of back at Worksop’s home ground, Central Avenue. Worksop were thought to be in financial difficulty at that time and some believe they were swayed by the prospect of a lucrative payoff – something that’s never been confirmed.

Either way the decision proved disastrous. The evening before the replay, the Worksop players were wined and dined on an all-expenses-paid trip around London with a posh meal followed by a show at the Palladium. The players did too much wining, staggering back to the hotel blind drunk. Goodness knows how they got up for the game the next morning.

The team were spent, both physically and mentally. Someone remarked afterwards how it was like trying to climb Mount Everest twice in three days. Disappointment and anger at being denied the chance of giving Spurs the run-around back home turned into resignation.

Worksop gave a shadow of the spirited performance the 21,000 spectators had witnessed just days earlier and were battered 9-0. Only their keeper, Jack Brown, put up any sort of resistance, his efforts preventing the score from being 19-0.

After the first-leg draw, fans back in Worksop had waited eagerly at the train station to give the players the hero’s welcome they deserved. But they never arrived. When the defeated team finally arrived back home, the Worksop fans were seething, knowing their team were incapable of being beaten by such a margin.

But their disgust was directed at the sub-committee, mainly the chairman AJ Tomlinson. This was, after all, not the first time he had agreed to switch a cup tie for financial gain. In 1908, Worksop had been drawn at home against Chelsea but Tomlinson agreed to travel to Stamford Bridge where the Tigers lost 9-1.

It became a PR disaster. Fans lost trust in the club’s management and many supporters vowed to never step foot in Central Avenue again.

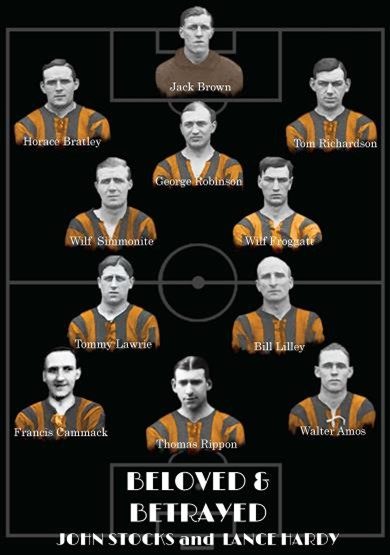

The story of that fateful day in January 1923 has been infamously retold throughout generations of Worksop fans. But the granddaughter of one of the Worksop strikers knew nothing about it until she chanced upon a book called Beloved and Betrayed written for the centenary of that notorious game.

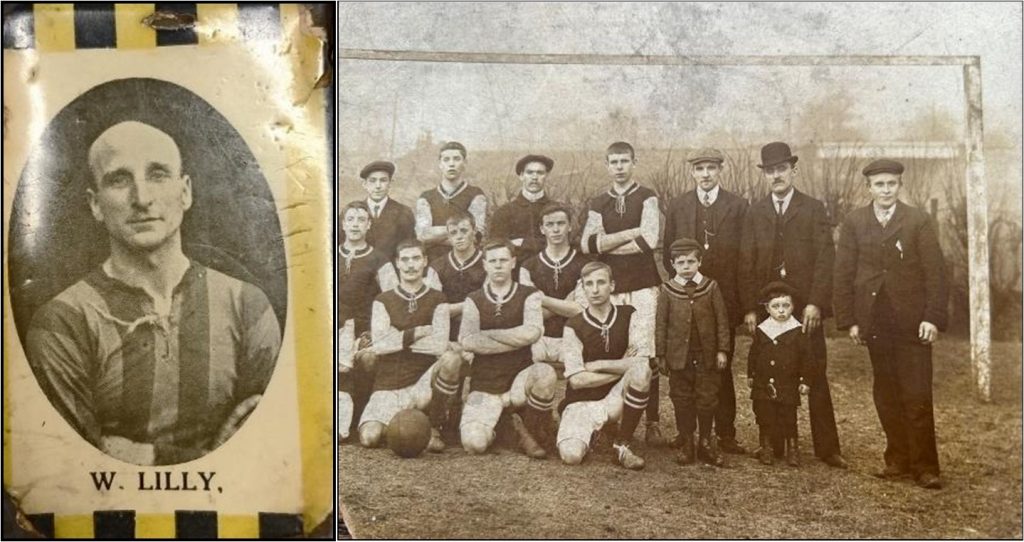

Liz Crowcroft’s grandfather William ‘Bill’ Lilley was a striker for Worksop Town in their 1920s heyday but she never knew much about his time in amateur football.

So it came as a surprise to chance upon a book cover bearing his photograph in Worksop Town’s amber and black striped kit when visiting the Millennium Galleries in Sheffield. Even more so of a coincidence that it was the day after the funeral of her mother – Bill’s only daughter, Hilda.

Liz and her husband John had been to collect Hilda’s belongings from the Northern General Hospital in Sheffield last December. Having travelled from their home in Mexborough, they decided to stay in the city for the day to have a browse around a Christmas fayre in the Winter Gardens.

“I stopped to look at this first table and John went wandering off through to the Millennium Gallery. Then he was beckoning me over pointing to this pile of books on a table. I couldn’t believe my mum’s dad was on the cover. What had made us go there on that very day, the day after Mum’s funeral?” Liz said.

She grabbed five copies – one each for herself, her sister, and her three daughters – and couldn’t wait to get home to read it. What lay inside the pages was a revelation to Liz, with one of the first chapters dedicated to her Grandad Bill. The book uncovered many aspects of Bill’s life that she’d never known before.

“Reading the book was like an episode of ‘Who Do You Think You Are’. The saddest thing is that my mother never knew anything about the book. She’d have been so proud as her dad was her hero. He was the kindest man who’d do anything for anyone; always very dignified, quiet and calm.”

Bill was born in Sheffield in 1890 and moved to Darfield in Barnsley when he met his wife. He’d originally played for Wombwell but was poached by Worksop Town in 1913.

Before the First World War, Bill had been one of the best footballers in the Midland League. A prolific striker, in his first few months at Worksop he scored 12 goals in 18 appearances and would often find a £5 note left in his boots when he went to get changed – equivalent of around £400 in today’s money.

Bill was on the watchlist of clubs like Sheffield United and The Wednesday but sacrificed a chance of having a top-flight football career to join the war effort. He volunteered with the Football Battalion, part of the Middlesex Regiment, a Pals-esque battalion comprising of professional and amateur footballers. He survived the war but the Sheffield clubs’ interest in him had gone and so he remained with Worksop Town in the amateur leagues.

Another thing the war stripped him of was his hair. A shelling left him concussed which led to premature baldness. Back home on the football pitch he gained the nickname ‘Old Bill’ or ‘Grandad’ because his lack of locks made him appear much older than his years.

“Before reading the book, I never knew how he lost his hair. I used to think it was because he always wore a flat cap – he had one for every occasion. They joked he looked older, but he was still always lean and fit even into his late 60s,” Liz says.

Liz also never knew that she and her grandad shared the same profession. He’d been a schoolteacher before the war. Liz and her sister – Bill’s only grandchildren – were also both teachers. He never went back to teaching after the war and instead became a miner at Wombwell Colliery.

Another uncanny twist is that both of Liz’s daughters and all three grandchildren have followed in Bill’s sporting footsteps, playing women’s or junior football in South Yorkshire.

Amazed by what she’d read, Liz set out to track down the two authors of the book: football historian, John Stocks, and Lance Hardy, a celebrated sports journalist.

Both born in Worksop, they shared a love of Worksop Town FC and its history. John was already collating the history of the club for a series of books, while Lance had planned to chronicle the infamous Tottenham game.

However, Lance was sadly diagnosed with a brain tumour and passed away just six months later in August 2021 aged 53. It was his dying wish that John finish the book in his memory and gave him strict instructions to launch it in Tottenham on the 100th anniversary of the FA Cup game – 13th January 2023.

In the book, there are 25 chapters that give an insight into the history of both clubs, their 1922/23 FA Cup campaigns, and the aftermath of their cup tie. The late John Motson called it an ‘absorbing story beautifully curated’.

John has also included information about what became of the Tigers team. Some players turned their backs on football after that season. But many others had stints with other non-league and professional clubs. Two players rose to great heights, those being goalkeeper Jack Brown and striker Wally Amos.

Jack Brown’s performance in both Spurs games grabbed the attention of league clubs and he signed for The Wednesday not long after his return home from London. He stayed with the Owls for 14 years, becoming Division 1 champions in 1929 and winning the FA Cup in 1935. He also played for England six times after getting his first call up in 1927.

Wally Amos was the Tigers player who humbled the Spurs team the most. Former captain Tom Clay wrote in his autobiography that one of the biggest run arounds he’d ever had in his career was against Amos. He signed for Bury in the summer of 1923 and became their most accomplished player. Today he is still on the record books as Bury’s third best goal scorer with 122 goals.

Beloved and Betrayed is priced at £8.99 and available to buy at Maurice Dobson Museum in Darfield, Millennium Gallery, and Kelham Island Museum.