Like many families during the First World War, the Elmhirst family from Worsbrough were split between the front line and the home front.

But a series of round-robin letters written over a five-year period from around the world would keep the siblings connected through their wartime separation.

Over a hundred years after they were written, 70 letters survive, powerfully illustrating the siblings’ personal experiences during the war and the family banter that didn’t diminish despite great tragedy. The letters have been compiled into a book by one of the sibling’s sons and provide a fascinating piece of Worsbrough history – and something that is unlikely to be replicated in the age of smaller families and internet communication.

The Family Budget 1914-1919 was first published ten years ago by Paul Elmhirst, a retired solicitor who once headed up Elmhirst & Maxton Solicitors, which has since become Elmhirst Parker Solicitors. The book collates the letters that Paul tracked down, and also gives biographies of his father, aunt and uncles who would ultimately go on to shape many aspects of life in Barnsley and beyond after the war.

There are traces of the Elmhirst name throughout Barnsley, from road names to a former school and of course the solicitors’ firm in the town centre.

The history of the family dates back to the 14th century when Robert Elmhirst was fined four pence for allowing his two horses to stray onto a meadow belonging to the Lord of the manor.

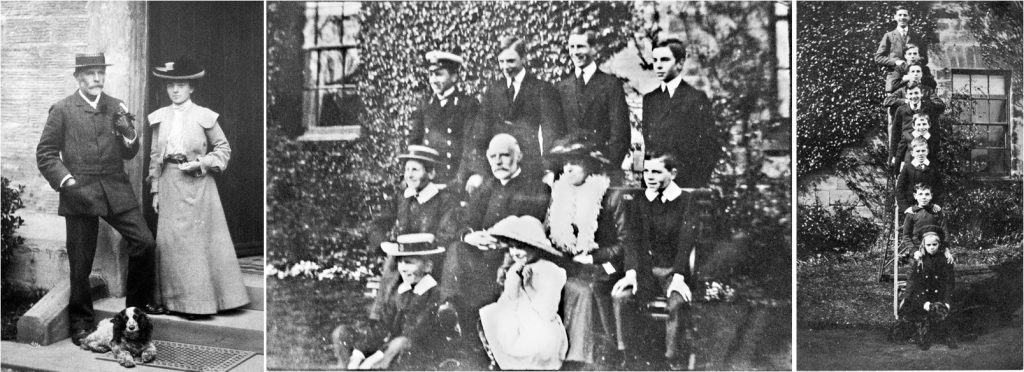

But this particular dynasty of the Elmhirsts were seven brothers and one sister born within a ten-year period from 1892 to 1902: William ‘Willie’, Leonard, Ernest Christopher ‘Christie’, Thomas ‘Tommy’, James Victor ‘Vic’, Richard ‘Richie’, Alfred Octavius ‘Pom’, and Irene Rachel. Another child, Edward, born between Tommy and Vic, died in infancy at just a few months old.

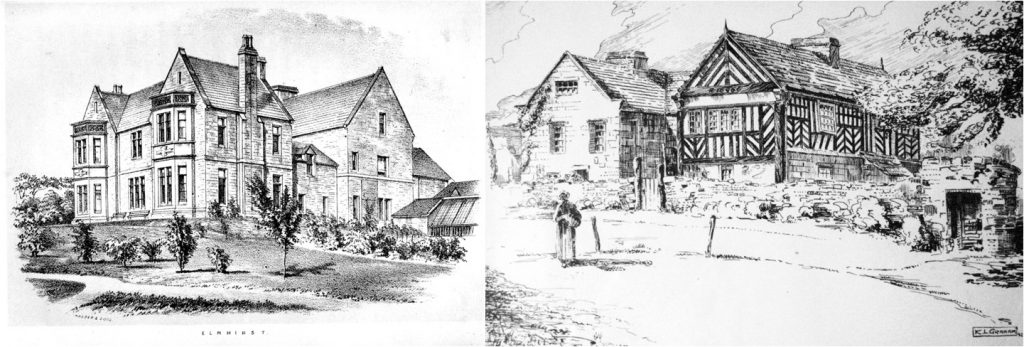

Their father was Reverend William Heaton Elmhirst from Laxton who had inherited his family’s 500-acre estate in Worsbrough in the early 1900s. He and his wife Mary moved the family back to Barnsley in 1905 to take residence at a rented property, Pindar Oaks, which would later become Barnsley’s maternity hospital. Once his mother died, William and his family then moved to Elmhirst Farm in Worsbrough.

Generational wealth acquired since the 16th century afforded them a lifestyle of house staff and prestigious public school educations. The family were rich due to the coal buried under the estate, along with various properties including Ouselthwaite Hall and Round Green as well as small farms at Coumes, Foldrings and Bitholmes in the Deepcar and Outibridge areas.

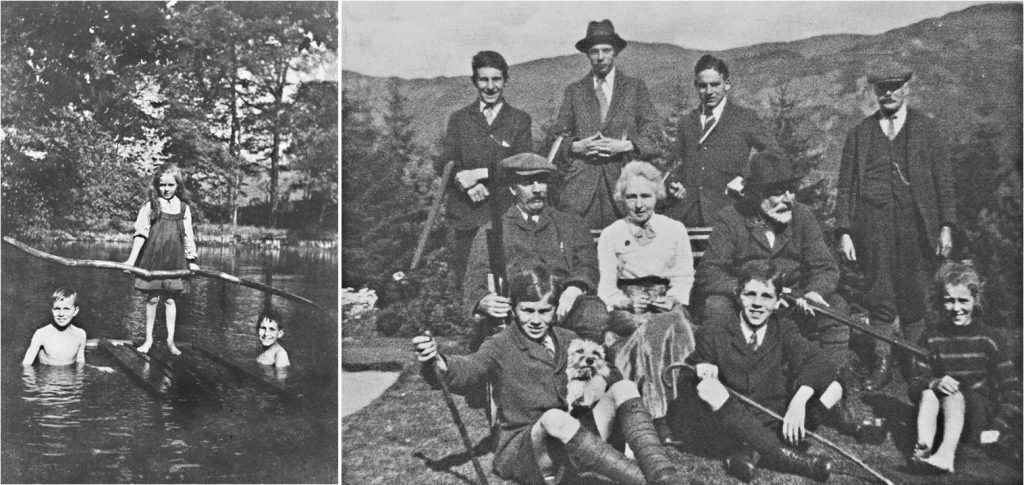

At Pindar Oaks and later Elmhirst, they had horses, ferrets and bantams. The brothers played cricket, rugger, and golf, and all eight of them went shooting from an early age. Holidays were spent ‘gricing’ (what they called grouse shooting) in Lassintulich, Scotland, going by train before Papa got his first motorcar – which would be driven by chauffeur.

But despite their status as landed gentry, the Elmhirsts were never seen as toffs.

From a young age, the children were used to being positioned across the country, first at prep school and then at their respective boarding schools which included Brackley, Malvern, Marlborough, Repton, Rugby, Winchester and the Royal Naval College at Osborne on the Isle of Wight.

But despite paying for his children’s educations at prep and public school, Papa Elmhirst saw university as an unnecessary luxury. Most of the Elmhirst boys went into the military after school, except for Leonard who followed in his father’s footsteps to read Theology at Trinity College, Cambridge with a view to being ordained into the ministry.

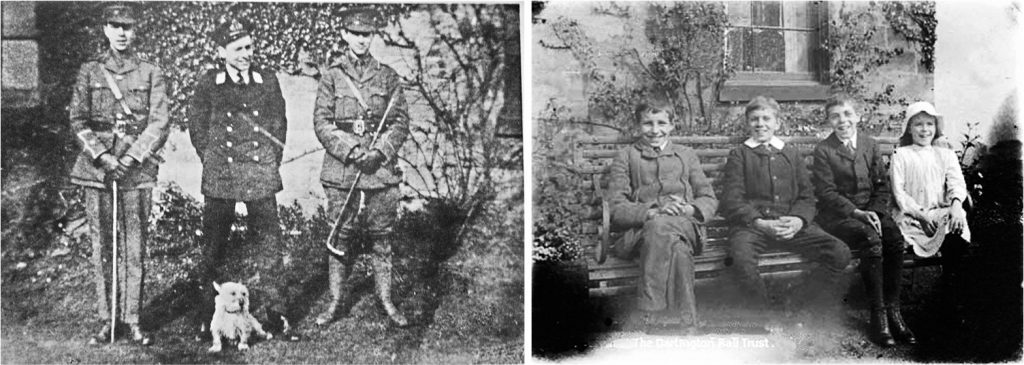

As war broke in July 1914, the eldest four siblings, who were by then aged between 22 and 19, were each involved in the war efforts in some capacity. The three teenage boys, Vic, Richie and Pom, were at school, while Irene Rachel was at home in Barnsley.

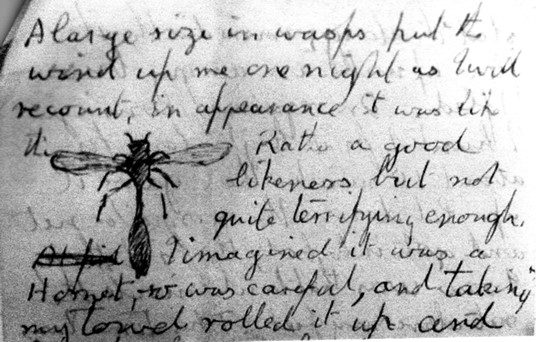

Leonard instigated the idea of the letter writing scheme. With no time to write to all seven siblings separately, he would send one letter that would be sent, in turn, to all of the siblings, with each of them adding their own letter into the collection. Once it came round to them again, they’d swap their old letter for a new one. He called it the Family Budget, or FB for short, named after an obscure definition of a sack and its contents.

The first letter was sent by Leonard from Cambridge in October 1914 and over the next five years the siblings penned their thoughts from their lodgings around the world including Matlock, York, India, at sea, and somewhere in France.

For the eldest siblings in the midst of the conflict, they would never have travelled as far from home before. Receiving the FB was vital to their morale, even if it was just once a year at some point – it could often find itself with one sibling for weeks or months at a time before it was passed on down the line.

They wrote about their achievements and whereabouts. Willie having to organise Christmas dinner for his platoon with 360lb of Turkey and 92 dozen mince pies. Leonard’s mission in India visiting the Taj Mahal, seeing the Himalayas, getting dengue fever and having a monkey as a pet. Christie being commended for his performance as a champion lass in a Sister Suzy concert at Belton Park’s Machine Gun Corps Camp. Tommy’s first ride on a motorbike where his cardboard box full of belongings blew off into the road.

The younger four wrote about the highs and lows of school life. Vic using a hanky in his pocket to soften the blow of regular cane beatings. Richie being a keen photographer, bugler, skater and winning the schools’ cup for sniping. Pom getting over a greenstick fracture and teaching himself to knit. Irene Rachel learning to swim and skate with the governess at home before overseeing maintenance of her school’s tennis and cricket pitches.

Unsurprisingly, words of the Great War filled their letters. Of training, camp life and promotions. Willie getting his captain commission, Tommy’s new airship, Christie eating bully beef, cucumber and melon in Gallipoli. Rifle and machine gun courses. Of the younger boys’ hopes to get onto an army class or the Officers’ Training Corps. Instructions to ‘keep off the mines’, ‘don’t get nipped by a fast one’ and ‘bring me back a German helmet’.

But most of all they wrote about the mundane and the ordinary, reminders of home and the life they’d all hope to come back to.

“What a day it will be if we all assemble at Pindar Oaks again (if we ever do).” Christie wrote in December 1914.

That prophesy would sadly never come true. Christie was killed in Gallipoli in August 2015, and Willie died on the Somme in November 1916.

The rest never mentioned their two brothers’ deaths in their letters that followed, unable to truly express how they felt. But the tragedies would change them as people, particularly Leonard. He became bitter about the unnecessary wastage of war and renounced his faith and plans to take holy orders.

Communication between the surviving six continued until November 1919 when the second chapter of their lives would begin.

Leonard was on his way to America to study at Cornell University, where he would meet an American heiress who would change his fortunes – and that of his family. Tommy was on Anglesey as the commander of the Naval Airship Station, about to join the newly formed RAF. Vic, having been at Sandhurst after leaving Marlborough, joined the York and Lancasters and was in Mesopotamia (what is now Iraq) between Kut and Baghdad. Richie was coming to the end of a short six-month stint in the Coldstream Guards and about to study agriculture at Cambridge. Pom had begun a career at their uncle Charles’ law firm in York. And Irene had become head girl at Brackley.

You can order copies of The Family Budget priced at £12.99 from www.ypdbooks.com

Who were the Elmhirst family?

William ‘Willie’ (1892-1916 aged 24)

The eldest Elmhirst sibling, Willie was educated at Malvern College before studying at Worcester College, Oxford. After graduating, he was articled to his Uncle Charles’ law firm in York. He then volunteered to join the army, serving with the East Yorkshire Regiment.

His regiment was posted to France where Willie became Captain of the 8th battalion. He died fighting on the Somme on 13th November 1916 and his remains are buried at Serre Road Cemetery.

Leonard Knight (1893-1974 aged 80)

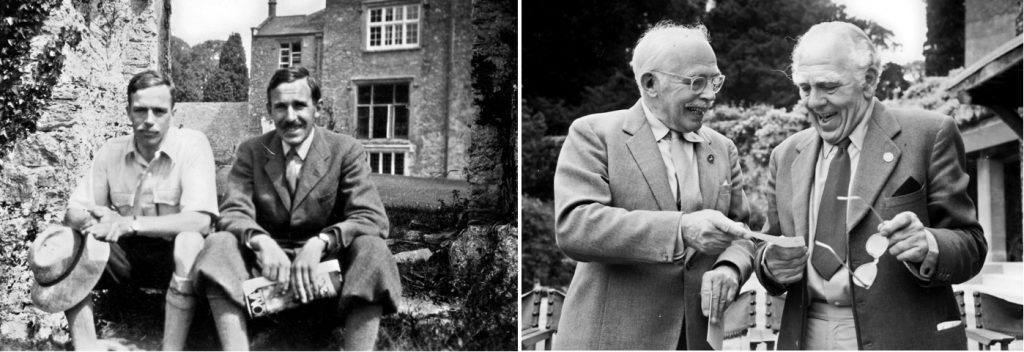

Leonard, affectionately known as Grandpa by his siblings, is perhaps the most well-known of all the Elmhirsts for his work establishing Dartington Hall together with his first wife, Dorothy Straight.

After going to school at Repton, Leonard went on to study History and Theology at Trinity College, Cambridge from 1912 until 1915. He graduated during the war but was unfit for military service so instead volunteered to be a missionary and aid worker with the YMCA in India.

In India he saw the extreme poverty and lack of farming expertise which would, coupled with his brothers’ deaths, change the direction of his career. To improve life in India he needed to understand modern farming methods so went back to education, studying agriculture at Cornell University, New York. He completed the four-year course in half the time, proving his position as the brains of the Elmhirst clan.

His true calling in life would emerge at Cornell by the meeting of two influential people: Dorothy Straight and Rabindranath Tagore.

Dorothy was the daughter of a US Navy secretary and had inherited a $15 million fortune aged 17, making her one of America’s wealthiest women. Her first husband, William Straight, died from influenza in 1918, leaving her widowed aged 33 with three children. She met Leonard in 1920 when he was seeking her financial support as president of Cornell’s Cosmopolitan Club for international students that was largely in debt.

Leonard also met Tagore, a Nobel Prize winning poet and writer who shared the same vision of tackling the rural decline in India. Leonard returned to India in 1921 as Tagore’s secretary where they set up an experiment in rural reconstruction designed to alleviate poverty through agriculture. Dorothy would also go on to finance their project, which saw them also provide holistic education for rural village people in creative arts and sport.

Back in England, Leonard and Dorothy, who eventually married in 1925, replicated Tagore’s principle when they bought a derelict 14th Century manor house, Dartington Hall in Devon. After renovating the site, they opened it as a co-educational boarding school with classroom learning replaced with a heavy focus on estate-based activities in farming and forestry.

Nothing was compulsory – no uniforms, no prefects, and certainly no corporal punishment. Dartington Hall was thought of as progressive, liberal and perhaps slightly rebellious.

A socialist’s paradise, students at Dartington Hall worked with their heads, hands and hearts in the hope it would create a generation of imaginative social reformers. It became a magnet for artists, architects, writers, philosophers and musicians and some of its alumni include artists Lucien Freud, and Michael Dunlop Young who founded the Open University and Which? consumer magazine.

The school also had a partnership with Northcliffe Secondary in Conisbrough and offered regular student exchanges between 1968 and 1974. They chose a school in the West Riding as Sir Alec Clegg was a trustee of Dartington Hall for many years.

Almost all of Leonard’s surviving siblings, as well as their offspring, benefitted from Dartington Hall, either as an employee or student. Indeed, the lives of Vic, Richie and Pom might have been different had there been no Dartington Hall – or financial help from Leonard.

The school eventually closed in 1987, but Dartington Hall is still home to a thriving music summer school that started in 1953, as well as a College of Arts and Schumacher College for sustainable education. Where once stood a tweed mill and glass factory are now shops, a cinema and food outlets for day visitors.

Ernest Christopher ‘Christie’ (1894-1915 aged 20)

Christie had no sooner left Malvern College before he enlisted in the army at the outbreak of the First World War. He was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 8th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment and was appointed a machine gun officer, becoming the prime target of enemy shelling if the machine gun emplacement was ever spotted.

His troop was stationed close to the Dardanelles in the Gallipoli campaign. By August 1915, he was missing presumed dead. His name is one of 20,000 engraved on the 30-metre high Helles Memorial on the Gallipoli Peninsula for the men whose graves are unknown or were lost or buried at sea.

Thomas ‘Tommy’ (1895-1982 aged 77)

Tommy had a remarkable military service career at sea, in the air and on land. His full title when he died was Air Marshal Sir Thomas Elmhirst, KBC, CB, AFC, with a total of 22 medals to his name.

He wanted to be a sailor from the age of seven and so his father sent him to the Royal Naval College, Osborne on the Isle of Wight when he was 12. He then progressed to being an Officer Cadet at Dartmouth before passing out in 1913. During the First World War, Tommy served in the Navy as a midshipman aboard the HMS Indomitable and took part in shelling of Turkish forts on the Dardanelles.

In 1915 he was one of 15 men selected to captain the new airships of the Royal Naval Air Service (the predecessor of the RAF) where he first needed to qualify as a balloon pilot. He then spent over three years searching for German U boats in British seas, before celebrating Armistice in 1918 by flying an airship under the Menai Bridge.

He subsequently joined the RAF and was posted to Malta before spending time at the British Embassy in Turkey’s capital, Ankara. During WWII, Tommy ran the operations room during the Battle of Britain before becoming second in command of the Desert Air Force. He was involved in planning the Normandy landings of Operation Overlord.

After the war he became Chief of Inter Service Administration in India and then the first Commander in Chief of the newly formed Indian Air Force when India gained independence from British rule. During his time in India, he was tasked with organising Mahatma Gandhi’s funeral when he was assassinated in 1948.

Tommy retired from the military in 1950 after 42 years’ service. Three years later he was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Guernsey, a post he held for five years, during which he welcomed the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip on their inaugural visit to the island.

He married twice, first to Katherine Black until her death in 1965 and then to Marian Ferguson, grandmother of Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York.

James Victor ‘Vic’ (1898-1958 aged 59)

After schooling at Marlborough, Vic enlisted in 1917 and went to Sandhurst before transferring to the Royal Flying Corps. However, the end of the war meant no more pilots were needed so he joined the York and Lancaster Regiment who were sent to Mesopotamia (Iraq).

With Leonard’s help, Vic bought himself out of the army and followed in his older brother’s footsteps to Cornell to study agriculture. He was then invited to work at Dartington Hall as an estate steward, but soon became temporary head teacher at the school. Vic stayed at Dartington for many years as a general administrator, adviser to the trust, and manager of the school farm.

Richard ‘Richie’ (1900-1978 aged 77)

Richie was at Rugby during the war and when he left in 1918 was sent to the Household Brigade Officers Cadet Battalion in Bushey. He subsequently moved into the Coldstream Guards where he stayed for six months.

Another of the Elmhirst siblings to benefit from Leonard’s influence, Richie was asked by the Dean of Magdalene College, Cambridge to study agriculture there. But he failed his exams and so ended up back in South Yorkshire working on the Frickely estate owned by the Warde-Aldam family of Hooton Pagnell.

Later, Leonard invited him to Dartington Hall to run the poultry department where he met his first wife, an American dancer with whom he had a daughter. However, he left Devon in 1936 and headed for Chicago to study social philosophy.

During WWII, Richie joined the American Air Corps as a private before being pulled out after eight days to become an instructor. He then became a lieutenant and fought at the Battle of Iwo Jima in the Pacific War.

When the war ended in 1945, Richie married his second wife, Morna, and the couple ran a farm at Clackmannanshire

Alfred Octavius ‘Pom’ (1901-1995 aged 94)

The youngest son, Pom was the eighth child, which led to his middle name Octavius. He was schooled at Winchester College and then was articled to Uncle Charles’ law firm in York. He failed his law exams twice and would have either sold cars or emigrated to Australia if Charles hadn’t encouraged him to try and pass third time lucky – which he did.

Pom would be instrumental in modernising the estate back in Worsbrough, bringing their original ancestral home of Houndhill back into the property portfolio after 250 years.

Houndhill, a Tudor farmhouse, had been built in the late 16th century and was inherited by Richard Elmhirst who worked as a debt collector for Cavalier, Sir Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford. During the English Civil War, Sir Thomas was executed and Richard too feared for his life. He had Houndhill fortified with two towers, an incomplete surrounding wall and had a Dad’s Army-like squad of 40 inexperienced soldiers to defend it.

An attack on Houndill was made in 1643 by Sir Thomas Fairfax, Cromwell’s commander-in-chief, who spared Richard’s life. Richard went on to have nine children and Houndhill eventually passed down to his granddaughter Elizabeth who married a Copley which indirectly led to the loss of Houndhill to the Vernon-Wentworth family of Wentworth Castle.

In 1932, Pom negotiated the re-purchase of Houndhill with Captain Wentworth on behalf of Leonard, first in line to the estate. After the death of their Papa in 1948, Leonard gifted Houndhill to Pom who lived there until he died in the mid-90s.

People thought of Pom as a squire, but he was a staunch Labour supporter who was friends with Arthur Scargill who lived nearby. He was involved in many aspects of the community, as a school governor, chairman of the district council, founder of Worsbrough Young Farmers, and chairman of South Yorkshire Archives. He was also a trustee at Dartington Hall for over 50 years.

Pom did all this alongside running the successful Elmhirst Parker Solicitors which had offices in Selby and Sherburn-in-Elmet before taking over another law firm in Barnsley town centre. When he died aged 94, he was the oldest solicitor in England to still hold a practicing certificate.

He and his wife Gwen had four children – Richard, Paul, Elizabeth and Tim – who were all brought up at Houndhill and went to the local Ward Green School before going to Dartington Hall.

Richard ran Round Green Deer Farm until 2019; Paul took over the law firm and has been chair of trustees at Cooper Gallery for over 50 years; Elizabeth moved to London; and Tim stayed in Worsbrough where he became a farmer.

Irene Rachel (1902-1978 aged 76)

The first and only daughter, Irene Rachel was educated by governess at Pindar Oaks during the war. She spent her days on the family farm tending to their horses, ferrets, chickens and her beloved and mischievous terrier, Conus. Having seven older brothers meant she was very much one of the boys, playing sports, going shooting, catching rats, climbing trees and messing about in the pit ponds.

Irene went to boarding school at Brackley in 1918 where she excelled at cricket and tennis and became head girl.

She became an attractive young woman and was asked to act as hostess for Edward, Prince of Wales’ visit to open Barnsley Town Hall in 1933 after His Royal Highness requested a pretty woman to sit next instead of an Alderman.

Around the same time, Irene was awarded an MBE for her work with boys’ clubs in the town.

She went on to marry a soldier and joint master of the Badsworth Hunt. After being demobbed from the army at the end of WWII, he tragically died in 1935 after being thrown from a horse while hunting, leaving Irene widowed with two daughters. After that, she moved to a farm in Twyford near Reading and never remarried, instead spending her time as a county councillor.