One is a rural village in Barnsley known for its stage of rolling green countryside on which stands a stately home and folly castle; the other a remotely romantic Italian lakeside town flanked by the amphitheatre-style Adamello mountain.

Poles apart in characteristics and distance. Yet banded together in a shared admiration for one very influential woman whose life story was preserved in the many letters she famously wrote.

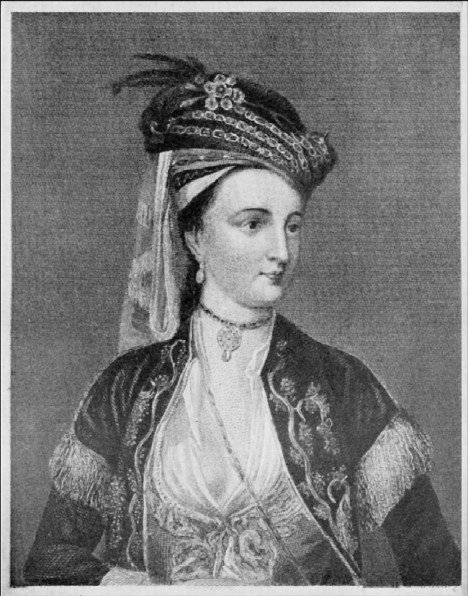

For Stainborough in Barnsley and Lovere in the Lombardy province of Italy both bear monuments to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the celebrated travel writer and poet who once lived at Wortley Hall.

At Wentworth Castle Gardens, an obelisk dedicated to Lady Mary has stood proudly over the manicured grounds for almost 260 years. Erected in 1750 by William Wentworth, 2nd Earl of Strafford, the obelisk is thought to be the oldest monument in the UK dedicated to a non-royal woman and stands in recognition of her work to bring the smallpox inoculation to Britain almost 300 years ago.

Over 1,000 miles away in Lovere, a quayside promenade with transparent glass barriers adorned with her own words was named in Lady Mary’s honour in 2016, in remembrance of the woman who spent ten years of her later life in the town, which she considered ‘the most beautifully romantic I have seen in my life.’

She was not wrong. Lovere, which is perched at the top of the serene Lake Iseo, regularly takes part in the Most Beautiful Villages in Italy competition and was the only Lombardy town to finish in the top 20 in 2018.

However, even 250 years after Lady Mary’s residence, the Bergamo town’s rugged and primitive beauty is yet to be discovered by tourists who favour the more well-known of northern Italy’s idyllic lakes, Como and Garda.

Lady Mary left her former life and family behind for a quieter existence. She bought a deserted palace, dairy house and farm for £100 and traded her high society crowd for time spent doing needlework or caring for the many poultry on the farm.

With its tree-lined quay, splendid palaces and shabby backstreets, the Italian charm enveloped Lady Mary into its fold. In return, she introduced them to traditional British delicacies like custard, mince pies and plum pudding; but the Italians were horrified by the ‘unnatural’ idea of a syllabub.

The posthumous promenade is not the first idea of a shrine to Lady Mary. While a resident, the town wished to create a statue in Lady Mary’s honour which she declined many times.

‘This little town thinking themselves highly honoured and obliged by my residence: they intended me an extraordinary mark of it, having determined to set up my statue in the most conspicuous place. The marble was bespoke, and the sculptor bargained with before I knew anything of the matter; and it would have been erected without my knowledge, if it had not been necessary for him to see me to take the resemblance.’

To Countess of Bute, 1751

But how did this colourful character and literacy genius of British aristocracy become a mainstay name in the Italian way of life?

Born in 1689, the eldest child of Evelyn Pierrepont, 1st Duke of Kingston-Upon-Hull and his first wife, Mary spent her early years at the family’s seat of Thoresby Hall in the Dukeries, North Notts where she first established her flair for writing.

Her mother died when Mary was three and so she was raised by her grandmother while her father spent much of his time at the Houses of Parliament as a Whig politician.

With girls being denied a classical education, Mary stole hers from her father’s library, teaching herself Latin, a language which had always been preserved for men. By the age of 14, Mary had written two albums of poetry and two novels, one being an epistolary made up of letters.

As a young woman, Mary forged a name for herself amongst the royal court and poetic society, thanks in part to her marriage to Edward Wortley Montagu of Wortley Hall.

To the disapproval of her father, Mary and Edward eloped in 1712 following a clandestine letter-based courtship. Evelyn had insisted that his daughter be betrothed to Clothworthy Skeffington, heir to the Irish Massereene peerage, having rebutted her calls to marry Edward, a lawyer of the Inner Temple and a fellow Whig politician.

However, her heart remained with Edward, a relationship with whom she hid from her father by writing to his sister, Anne.

‘Pray tell me the name of him I love, that I may (according to the laudable custom of lovers) sigh to the woods and groves hereabouts, and teach it to the echo.’

To Anne Wortley, 1709.

Her father tried hard as he could to force her to marry Skeffington. In 1712, she wrote she was to be sent to the family’s Wiltshire seat, West Dean against her will. However, she managed to escape and eloped with Edward in the August of 1712.

‘I cannot easily submit to my fortune; I must have one more tryal of it. I send you this Letter at 5 a Clock, while the whole familly is asleep. I am stole from my Sister to tell you we shall not go till 7, or a little before. If you can come to the same place any time before that, I may slip out, because they have no suspicion of the morning before a Journey. Tis possible some of the servants will be about the house and see me go off, but when I am once with you, tis no matter.— If this is impracticable, Adeiu, I fear for ever.’

To Edward Wortley, 1712.

The year after their marriage and now living in London, they welcomed a son, Edward. In 1714 the Whigs came into power, with Edward Snr. appointed as Turkish Ambassador in 1716. The family moved to Vienna before settling in Constantinople, now Istanbul, where they welcomed their second child, Mary.

Lady Mary documented her voyage to the Eastern world in illustrative detail in her Letters from Turkey series, and it is the vivid insight into the Ottoman Empire that first gained her the reputation and standing amongst the great writers of her time.

As a woman, she had access into places her male predecessors had been barred entry and so her findings broke down the misconceptions about Eastern religion, traditions and treatment of women, giving a more accurate account.

She was charmed by the Ottoman women she met, and they by her.

‘I must not omit what I saw remarkable at Sophia, one of the most beautiful towns in the Turkish Empire, and famous for its hot baths…

I was in my travelling habit, which is a riding dress, and certainly appeared very extraordinary to them, yet there was not one of ’em that showed the least surprise or impertinent curiosity, but received me with all the obliging civility possible. I know no European court where the ladies would have behaved themselves in so polite a manner to a stranger.

I believe in the whole there were two hundred women, and yet none of those disdainful smiles, or satiric whispers, that never fail in our assemblies, when anybody appears that is not dressed exactly in fashion. They repeated over and over to me, “Uzelle, pek uzelle,” which is nothing but, “Charming, very charming.‘The first sofas were covered with cushions and rich carpets, on which sat the ladies, and on the second their slaves behind ’em, but without any distinction of rank by their dress, all being in the state of nature, that is, in plain English, stark naked, without any beauty or defect concealed. Yet there was not the least wanton smile or immodest gesture amongst ’em. They walked and moved with the same majestic grace which Milton describes of our general Mother.’

To Lady — 1717

In the segregated Turkish zenanas, or female households, Lady Mary also witnessed smallpox inoculation, or variolation, taking place.

Mary had lost her younger brother William to the disease in 1713 aged 20 and had also had a severe case herself in 1715 which had tainted her beauty. While there, she had her son inoculated and brought the practice back to Britain on the family’s return in 1718.

However, Western doctors were sceptical and dismissed her idea due to its Oriental background. Variolation consisted of scratching pus from an infected person into the skin of the uninfected to promote immunity.

A smallpox epidemic hit Britain in 1721 and Lady Mary was quick to have her daughter inoculated, the first on British soil. She persuaded Princess of Wales, Caroline of Ansbach, to test the treatment on prisoners awaiting execution; they survived and were released. Having been convinced, the Princess of Wales had her own two daughters successfully inoculated.

Some 80 years after Lady Mary first brought the Turkish practice back home, a safer vaccine using cowpox was eventually developed by Edward Jenner.

Back on home turf after her Turkish expedition, Lady Mary and her family moved to Twickenham where it is thought she and her husband lived a loveless marriage, purely a formal agreement to save face.

Instead she focused on writing and editing her letters, which she chose not to publish but which still wound up being circulated amongst her social circle and beyond.

By 1736 and having been estranged from her husband for many years, Lady Mary became infatuated with Count Francesco Algarotti, a Venetian philosopher. At the same time, she also spurned the affection of Lord John Hervey.

Algarotti left for Italy where Lady Mary continued to write him before deciding to follow him to Venice in 1739.

She told her husband the relocation was for health reasons. ‘I never had my Health better than I have in this Climate, thô it is now cold. But here is a constant clear sun and instead of the dampness I aprehended the air is particularly dry, which I believe my constitution requir’d.’ – To Edward Wortley, 1739

The relationship was short-lived and Mary moved to Avignon, France for a few years before returning to Italy to Brescia before relocating to Lovere on her doctor’s orders.

Whilst here, she continued to write, this time to her daughter who had become Countess of Bute, married to John Stuart the future Prime Minister.

Her husband Edward died in 1761 and Lady Mary, then living in Venice, returned to England before passing away the following year in 1762.

Lady Mary’s legacy has since been written into the history books, more so for her smallpox findings. However, her letters and poems have inspired generation after generation of female writers and she is testament to the power of education in women.

‘If your Daughters are inclin’d to Love reading, do not check their Inclination by hindering them of the diverting part of it… People that do not read or work for a Livelihood have many hours they know not how to imploy, especially Women, who commonly fall into Vapours or something worse.’

To Lady Bute, 1750

Recently the National Trust, in partnership with Barnsley Council and Northern College, re-opened Wentworth Castle Gardens to the public where you can see the Lady Mary Wortley Montagu obelisk which is an important feature of the grounds.

Today, almost 300 years after Lady Mary’s pioneering inoculation concept, there is still a great deal of debate concerning vaccinations, particularly the efficacy of the MMR vaccine for children.