They say every cloud has a silver lining. But had it not been for the storm clouds calling off his beloved football as a schoolkid, Peter Elliott may never have gone on to set the pace to become one of Britain’s prodigious middle-distance runners who dominated the track in the 1980s.

As a former world-class athlete who won a plethora of medals at three of the four major championships, Peter is Rotherham’s most successful athlete at international level. His triumphant career would ultimately come full circle at his hometown’s Herringthorpe Stadium, from the very first starting pistol as a promising junior runner to the ultimate finishing line when injury led to early retirement.

Since his retirement from professional athletics, he has continued to influence the future generation of elite sportspeople, having spent the last 17 years working for the English Institute of Sport where he is now the director of operations.

His innate drive and determination to succeed at all costs has never left him, but neither has he forgotten his roots.

Like a lot of young kids growing up, Peter was never without a football and that was really the only sport that he engaged with. During his first year at Rawmarsh Comprehensive School in the 1970s, the indoor sports hall was being redeveloped so all PE sessions took place on the field opposite the school. When it rained, the football pitches became waterlogged so pupils had to do cross country instead of team sports.

On one occasion, an 11-year-old Peter was first over the finish line. The school had already completed their cross country trials but his sport teachers knew it would be a mistake to leave his name off the team sheet.

“I declined their invite. But they told me if I didn’t race on Thursday then I’d be dropped from the football team on Saturday. I was only ever interested in playing football, so I had no other choice but to race,” Peter says.

Peter had been unaware of his running ability, but it was clear he had the natural talent and stamina to become a front runner. As a 12-year-old unattached runner, he took part in the Rawmarsh Road Race on New Year’s Day 1975 where he was subsequently scouted by Rotherham Harriers. Peter quickly rose through the junior ranks with his hometown’s premier running club, winning four English Schools’ Athletics titles and setting a record time for the under 17s 800m of 1.53.3 in 1979.

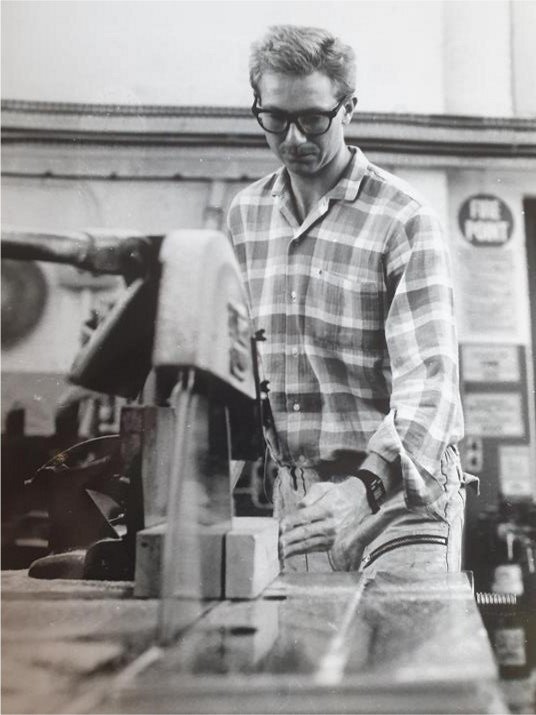

After leaving school at 16, Peter followed in his father Brian’s footsteps and took a job at British Steel where he worked as a joiner while continuing to train with the Harriers after he’d clocked off.

“Sport back then was very different. You ran because you enjoyed it. Of course, some runners had ambitions and once you got to a higher level it opened pathways to possibly going to the Olympics where, ideally, you’d win a medal – and gold at that.

“But there was no money or support in that era. You had to rely on self-funding your journey through parents or working to pay to travel to see your coach who was more often than not your nutritionist, strength and conditioning coach, and psychologist. Nowadays it’s great that athletes receive funding from UK Sport, raised by people buying a lottery ticket on a Saturday night, which enables them to focus solely on training and competing.”

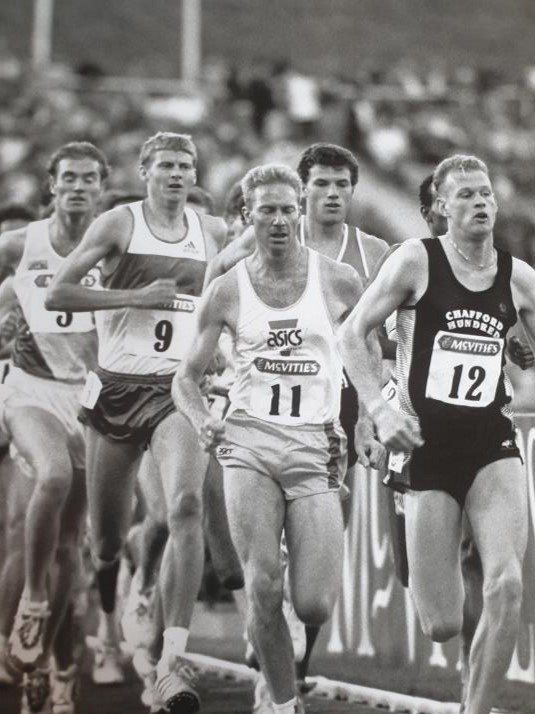

Throughout the early ‘80s, Peter competed at stadiums across the world, going on to be the northern 800m champion for two consecutive years and being ranked number two in the world for the indoor 800m. In 1982, he set the world record for the 4x800m relay with Seb Coe, Steve Cram and Garry Cook – athletes he’d previously been inspired by.

“I remember the whole nation stopped to watch Coe, Ovett and the team at the Moscow Olympics in 1980. Then the next thing I knew I was stood on the start line with them. Then I was beating them.”

Here was a working-class lad from Rotherham who had been catapulted into the gladiatorial arena amongst some of Britain’s finest, unwavering athletes. But Peter had fire in his belly and would prove that he’d earned his stripes. The late sports promoter, Andy Norman, once said of Peter, Coe, Cram and Ovett, if you were to build a brick wall in the middle of the track, one would stand and complain, one would run around it, one would try and climb over it, and one would run straight through it.

“I knew exactly which one I was, but couldn’t possibly comment on the rest…”

But unlike his fellow track stars, when 21-year-old Peter was called up to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, he was still working full-time in the steelworks. But by 1987 he’d decided he couldn’t continue to juggle training and competing while working full time.

“Something had to give. But I enjoyed work as it was an escape, somewhere I could switch off from athletics. And I liked who I worked with. If I raced well, the support from the lads was great. And if I didn’t, well I’d get some hammer from them on a Monday morning. I never needed to work with a sports psychologist that’s for sure!”

In the lead up to the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, British Steel offered Peter 12 months’ paid leave which he courteously turned down. Instead, he decided to continue working four hours a day, five days a week and strictly stipulated they only pay him for the hours he worked.

“Carrying on working gave me the discipline I needed. I had to be at work for 12pm, so I knew if I wanted to train I had to get up early. Then after I finished my shift at 4pm I still had plenty of time and energy to get back out running in the evenings without burning out.

“I tried being a full-time athlete for two years and it didn’t work. I’d stay in bed later as I had nowhere to be after training. Then the evening came and I didn’t have the motivation to go out again. Most athletes certainly couldn’t do it now and it wouldn’t suit everyone. But I guess I had an ‘I’ll show you’ attitude that I could do it all.”

The disciplined approach paid off. In the same year as Seoul, Peter won the Yorkshire 1500m title in Cudworth and set a new personal best for the Dream Mile in Oslo.

At Seoul, Peter was entered into the 800m and 1500m, meaning he competed in seven events over nine days. Unfortunately, he picked up a groin injury and needed injections of local anaesthetic to numb the pain before every race. He finished just outside of medals in the 800m and came second in the 1500m, something which Peter is still disgruntled by.

Hearing him downplay what I perceive to be a phenomenal achievement catches me off guard. Such a small fraction of people on this earth have the commitment and talent to win a place at the Olympics, let alone place in the top three in their discipline at the gold-standard sporting stage. But the more I listen, the more I realise achievement is relative to the journey and mindset an athlete has.

“I had a reputation for being an aggressive and hard racer. I was disappointed to only get silver at Seoul, but I trained to win. It’s hard for people to understand but when you’re an established athlete, all you aspire to is gold. Seb Coe had won back-to-back golds in the same event, so I felt like I’d failed to retain the title for Britain.”

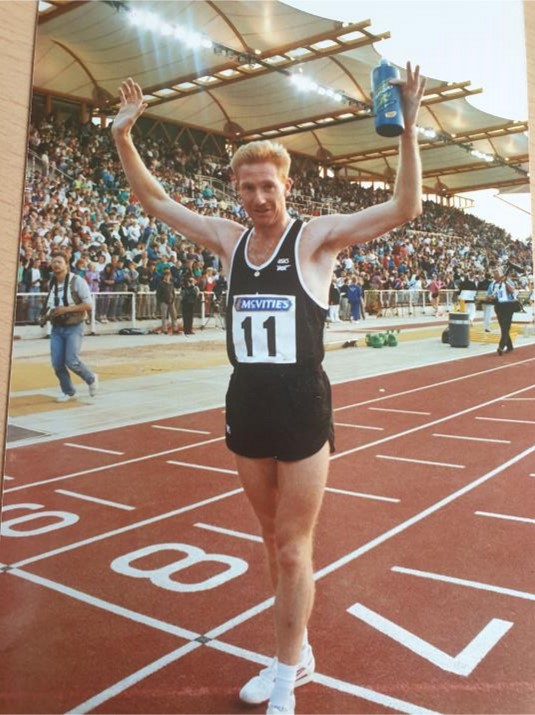

Two years later, Peter had his chance to show the world he could go the distance. During the 1990 season, he set three PBs in the 800m, 1000, and 1500m, claimed a world record for the indoor 1500m in Seville, set a British indoor mile record in the USA and won the New York Fifth Avenue Mile. He was also awarded an MBE for services to sport.

But his most memorable and special moment came when he went to the Commonwealth Games in Auckland and won gold in the 1500m witnessed by Her Majesty the Queen and Prince Phillip.

“I knew nobody could beat me and I had this aura around me. I guess it was one of those purple patch moments, those lucky times. My training and preparation had gone well and I was confident that nothing could go wrong. The Olympics might be the bigger event, but for me this was my proudest moment as I’d finally become a champion.”

Back home in Rotherham, Peter says the reaction at every major event was always immense, with the town taking ownership of their red-haired hero who had put Rotherham on the map.

“The people of Rotherham were always very supportive of my running. When I came home from the Worlds, the Commonwealth in ’90 and the Olympics the street was full of well-wishers. A very good friend of mine, David Haywood, told me how straight after my victory at the Commonwealth Games final in New Zealand (3am UK time) he drove over from the Stag to my mum and dad’s house in Rawmarsh with a bottle of Champagne to celebrate the win. What surprised him was that every house light was on as he drove there.

“You do not appreciate this kind of support when you go to the start line of the big championships and how much support there is for you back home. I always tried, where possible, to put Rotherham on the map hence whenever I could I‘d wear the black vest of Rotherham Harriers.”

Retirement happens to all athletes eventually, but Peter’s sporting days were cut short due to injury. Peter says he felt he had started training to get injured rather than compete, but the final blow came six weeks before the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona when he took part in a mile-long race at Herringthorpe – little did he know it would be his last.

Despite winning, he pulled his hamstring which would take at least two weeks to heal. Then he’d need rehabilitation and physiotherapy at a time when he should have been tapering down in preparation for the Games.

“My only intention of going to the Olympics was to win gold. Would I realistically do it with only six weeks to go? The answer was no, I’d lost too much. I didn’t need another Olympic blazer or tracksuit, so I withdrew to give the reserve plenty of time to increase their training.”

His eventual retirement came with no big announcement or charade. But his imprint on the sporting world wasn’t to be dusted away just yet.

Peter was asked to work for former long-distance Olympian, Brendan Foster’s company Nova International which founded the Great North Run. After eight years there, he was then headhunted to join the newly established English Institute of Sport which was launched in 2002. After 17 years with the company, Peter is now director of operations and oversees ten high performance centres across the country from Gateshead to Bath, with a centre of the same name in Sheffield.

The EIS is grant funded by UK Sport and works with Olympians and Paralympians to provide access to world-class equipment, sports science and medicine to improve and enhance performance. As head of operations, Peter’s role includes managing health and safety and ensuring the sites run effectively and efficiently – his responsibilities heightened throughout the Olympic cycle.

“The beauty is that now I have involvement in all sports, not just track and field, and it’s been great to witness the changes that have happened in the industry. Athletes have more pressure on them now, particularly as future funding is reliant on how they perform at the Olympics or other competitions. But their wellbeing is much more protected compared to 30 or 40 years ago. In my time, I put pressure on myself as I’d had to self-fund, but my only concern was me, my coach and my family. Team GB are just that – a team.”

And what about the future of Team GB? In his role at EIS and as president of the South Yorkshire Schools Athletics Association, Peter knows how important grass roots sport is. But in recent years, there have been concerns that participation, particularly at a local level, is trailing off.

“To move forward we need to appeal to the youth of today by looking at their interests. There will always be purists, but you’ll have noticed in recent years how the Olympics has moved away from a traditional focus. We now have events in surfing, mixed relays, BMX, and we had our youngest ever Olympian in Sky Brown who won bronze in skateboarding at just 13. At Paris 2024 there will be breakdancing, and who knows, in 2036 we might even have eSports.”

Whatever the future of elite sport, Peter Elliott will forever be one name that will remain ingrained in the history books of Rotherham and the world.