Most children on the eve of their 10th birthdays would be going to bed with excitement in their tummies, dreaming of opening presents, eating jelly and ice cream, and celebrating with classmates.

But the night before Rolf Heymann’s 10th birthday was the stuff of nightmares. He and his family spent the night locked in their cellar, fearing for their heads as axes came through each shutter on the house and screams echoed around their small German village. The next morning, all of Rolf’s schoolmates were gone, never to be seen again.

That night was 10th November 1938, Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, which started the Holocaust. Rolf and his mother Herta were a Jewish family living in Kerpen, outside of Cologne, when the Nazis massacred their village. Out of 133 Jewish residents, only six lives were spared – Rolf, his mother and aunt being three of them. The others were killed or sent to concentration camps.

But why were the Heymanns pardoned?

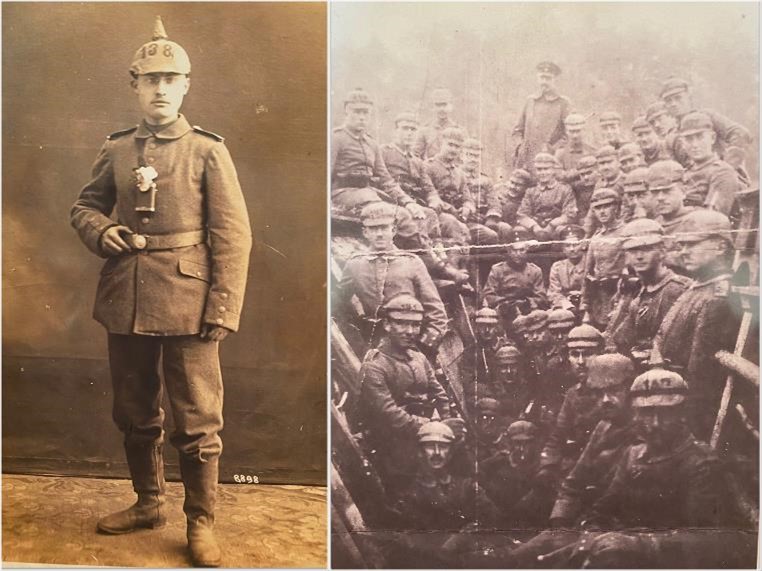

Rolf’s father, Philipp, was a war hero who had been awarded the Iron Cross (2nd class) aged 19 for saving a comrade’s life during the Battle of Ypres in 1914. As the Nazis came to desecrate the Jewish community at Kerpen, Rolf’s neighbour, a farrier, spoke of Philipp’s patriotism and gallantry. He’d passed away the year before Kristallnacht, but his heroism saved his son and wife who would shortly go on to start new lives here in Sheffield.

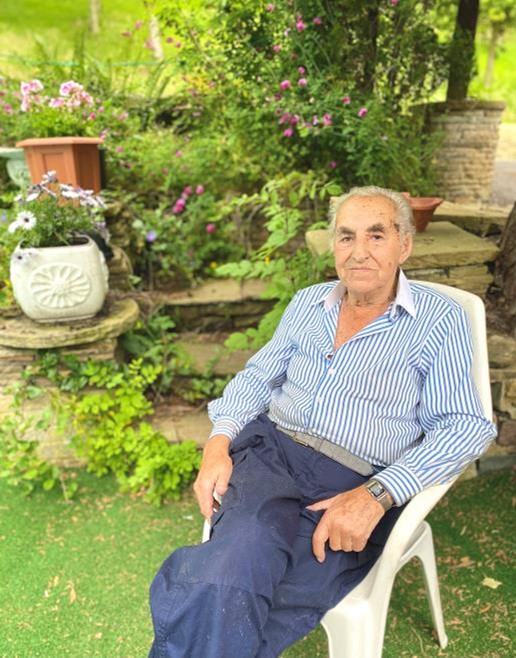

“My father’s bravery is why I’m here talking to you,” Rolf tells us as we meet at the now 92-year-old at his Bolsterstone home. Defying his years, Rolf is sprightly and sharp, speaking so eloquently about the life he has led. Never has a story taken so many fascinating twists and turns, with lots of hilarious anecdotes thrown in for good luck.

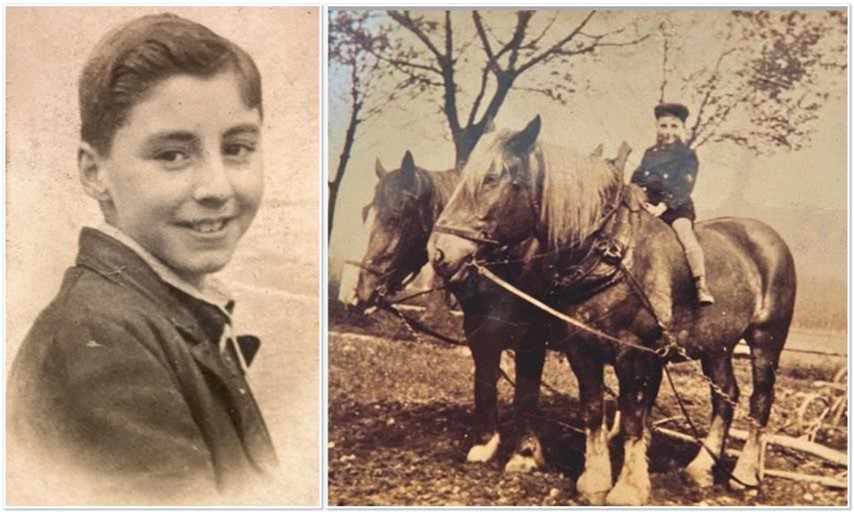

Rolf was born on 11th November 1928 – Armistice Day – into a wealthy German family who bred around 450 horses a year, mainly for the German army’s cavalry and haulage needs. In the 1920s, the family was worth around £160,000, so multi-millionaires in today’s money.

Philipp was still a teenager when he joined the German army in the First World War, where he was posted to Belgium to fight the British on the Western Front. Following a sustained attack from the Allies, a fellow German soldier had his legs blown off, with Philipp applying a tourniquet to stop him bleeding to death. For this single act of bravery he received the Iron Cross.

He was then sent to the Eastern Front to fight the Russians which is where he had his own foot shot off. With everyone dead around him, he laid in a crater for three days with only a cigarette butt to chew on. His leg became rotten and was forced to chop part of it off with his army issued axe, before he was found by the opposition who amputated his leg below the knee at their field hospital. But gangrene had set in. As Philipp could no longer continue his military service, he was sent home where he underwent a further amputation above the knee.

Losing a limb meant Philipp couldn’t take over the family’s farming and horse breeding business, so he was sent to Cologne to be an interpreter for the foreign office. His father worried his son would never marry or have children due to his disability, so he arranged a marriage to a girl called Herta from north Germany. The couple had one child, Rolf.

With her new husband away working in the city, Herta wanted to open a village shop to keep her busy.

“My grandad was very religious and told my mother she could only turn the front of the house into a shop if it closed on Saturdays – the Jewish Sabbath. But everyone knows Saturday is the busiest trading day, so she said if she couldn’t open then she wouldn’t marry his son. He had no other choice but to let her.”

When Rolf was growing up in the early 1930s, the Nazi party’s fascist ideologies were rife as Hitler rose to power. Rolf knew from an early age that he his strict orthodox upbringing was different to that of the Christian ‘Aryan’ children. No child is ever born hating others, but Rolf experienced unimaginable animosity from other young children who had been conditioned into following Hitler’s antisemitic views.

“I would wake up in the middle of the night to steal sweets and chocolates from my own mother’s shop just to prevent getting a beating from the Hitler Youth. But they still got me. I remember being around eight and having a large boil on my arm. My mother wanted me to be seen by a doctor, but I refused until the pain got too much to handle. When the doctor asked me to take my shirt off, my chest and back were black and blue from all the beatings I’d received.”

Rolf’s father died in 1937 aged 44 from gangrene that had laid dormant for almost 20 years, leaving Herta to raise their young son by herself. But Rolf says he will always be grateful that his father never had to witness what was to follow.

When hyper inflation hit Germany following WWI, Rolf’s grandfather had been wise enough to draw half of his capital out of the bank which he used to buy 80,000 gold coins equivalent to British sovereigns. Within six months, his remaining money was worthless. But worse still, Hitler took the gold from him. Today, the value of those gold coins would be in excess of £27 million. But the Heymanns lost everything, except for three gold coins which Rolf found in the bottom of the original trunk they were stored in when it was returned to him some years ago.

“It did me good to have nothing as I’d have been a real spoilt brat if it wasn’t for Hitler. My grandad spoilt me rotten as he never thought he’d live to see the Heymann name live on.”

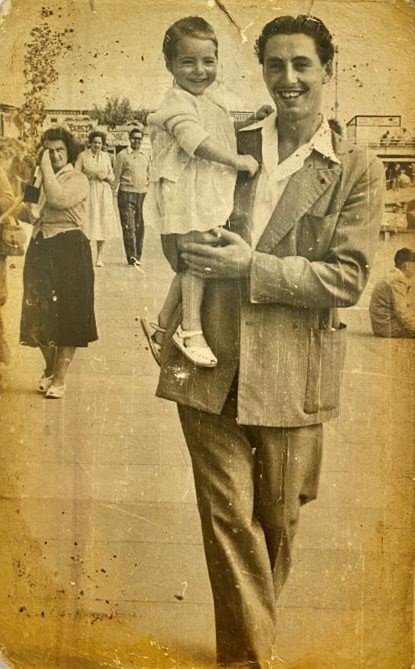

After the horrors of Kristallnacht, Germany was no longer safe for Jews, and Herta was desperate for her only son to escape persecution by the Nazis. At just ten years old and with a ten-shilling note in his pocket (about 50p), in June 1939 Rolf boarded the Kindertransport bound for Rotterdam where he then caught a ferry to seek asylum in Britain, never knowing if he would see his mother again.

Herta had originally planned for she and Rolf to emigrate to Johannesburg where she had family. But the South African prime minister at that time was a Nazi who stopped all Jewish immigration. Instead, they were to join her cousin who was living in Sheffield.

She managed to flee Germany a few months after her son, just two weeks before the war began. She was forced to sell their 16-room farmhouse for £400, and the 1,000 acres of land and two orchards for £600 – but it was take it or leave it. With the Nazis confiscating all Jewish gold and wealth, Herta had an ingenious, if not terrifying, idea to get one over on Hitler.

“Before she left Germany, my mother had all her teeth pulled out and a set of 14ct gold teeth fitted. How she opened her mouth I don’t know. Once she arrived in Sheffield, she had a set of false teeth made for £5 and sold the gold to the dentist for £165.”

Rolf and his mother lived with her cousin at Embassy Court flats, behind Park Hill in the city centre, where Rolf attended Park School.

“It was a very rough school, the kind where the kids would kick a house brick around if they had no football. The only English words I knew were yes and no, but they soon taught me some expletives.”

Rolf and Herta were together for two months before the 250 schoolchildren were evacuated, with Rolf being sent to a farm in Farnsfield near Mansfield. Herta took a position as a live-in maid for a Jewish family and would become a mother figure to the family’s two young sons after the own mother died six months after Herta began working for them.

Rolf spent four years at Farnsfield and returned to Sheffield aged 14 to start work. But by the time he reached 21, he’d already had 17 jobs in everything from farming to steelworks and even door-to-door sales. He just couldn’t settle.

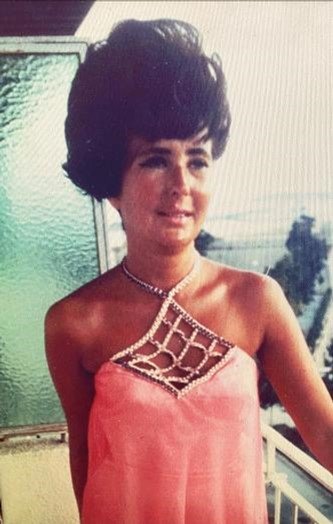

“You need to have luck in life. In Germany, my father gave us the good luck to evade the Nazis. And in Sheffield, luck came when I met my wife, Jacqueline, in 1950. I met her at a dance at City Hall; she was 19 and had split up from her boyfriend. At the end of the night I asked if I could take her home, but she said, ‘I don’t think you’ll want to when you know how far away it is’. She lived near Deepcar and I was only living on Ecclesall Road, so it would have been some walk.”

The pair married nine months later in February 1951 and would have celebrated their 70th wedding anniversary this year, but Jacqueline sadly passed away on Christmas Day 2019. Rolf still lives in the house where Jacqueline lived when they met.

Rolf says that he has been lucky that the British have always been very sympathetic towards him and he has never received any antagonism from anyone – anyone except his own mother, to the point where she threatened to take her own life if he married Jacqueline.

“When we first got together, I had to keep the relationship a secret from my mother as she disapproved of Christian girls. But I’d had bad experiences with Jewish families asking what hope, what prospect I really had in life – completely undermining the life I’d come from. I vowed never to marry a Jewish lass.”

While Rolf has since denounced his religious upbringing, Herta followed a very devout Jewish lifestyle and feared what people would think of her son marrying outside of his faith. Mercifully, when the couple found out they were expecting a baby six months after their wedding, Herta began to come round to the idea. She lived with them towards the end of her life and couldn’t have wished for a better daughter-in-law who helped care for her.

It is in those seemingly ordinary moments that hold extraordinary meaning. Had he never met Jacqueline at City Hall, his life may never have played out the way it did – and what a remarkable life Mr Heymann has led.

Jacqueline’s father was the manager of Bramall’s scrap merchants and managed to get him a three-month trial with the company.

“I’d been working as a lorry driver for a wine and spirits company earning £4 a week, and even on probation this job was £8 a week. But it was heavy going, stripping down old batteries for scrap and getting covered in acid. I couldn’t hack it and was ready to pack it in. But I finally got the knack after two weeks. After the three months, my wage went up to £12 a week, which was about double the average wage in the 1950s.”

Rolf struck up a great relationship with the company’s owner, Albert Bramall, who could speak better German than Rolf, having been posted in north Germany with the RAF during the war. The Heymanns used to babysit for Albert’s two sons and would become godparents.

Two years after joining Bramalls, Rolf decided to go it alone and start his own scrap business dealing with silversmiths and engineering firms, with Albert behind him all the way.

Then at 32, he retired.

A couple of years earlier in the late ‘50s, Rolf and Herta were contacted by a solicitor in Germany informing them they were to receive reparation from the German government to compensate them for their losses and exile at the hands of the Nazis. Rolf was to be awarded three lump sums, while his mother was offered £100,000 to call it quits.

“The best thing she ever did was turn it down. The second offer was monthly payments four-times that of the average British wage. She lived to be 91 so when she died in 1990, she’d accumulated far more than that original offer.”

Although it goes some way to softening the blow of losing their fortunes in Germany, Rolf tells us that the paltry sum Herta received for their home and land was made worse when a coal seam worth around £1.5m was found under the house after the war. The house is still there some 280 after it was built and now comprises of three three-bedroom flats, an antiques store, and ladies’ fashion boutique which goes to show the sheer size of it.

With luck on his side and cash in his pocket, Rolf spent five years travelling the world with Jacqueline and enjoying time at home before realising you couldn’t retire at 32. He didn’t need to financially, but Rolf went back to work at 37 when he then retired for a second time aged 80.

Hitler has a lot to answer for in Rolf’s life, but he really was the answer when HMRC came knocking in the 1990s.

“I had a letter from the taxman calling for a meeting which set the alarm bells ringing. I’d been in business 30 years, so why now? I’d lost my mother a few years before and she left everything to me. Had my accountant forgot to inform them?

“Every answer I gave them was truthful, but I was whittling they were going to stump me. Then the lady asked me if I had a swimming pool. How the hell did she know that? She wanted to know how long I’d had it and where it came from, so I told her. Then she asked me how I paid for it – in cash. And where did I get the cash from? One word. Hitler. Well, the look on her face.”

No Rolf Heymann story is complete without a few laughs thrown in and the swimming pool saga is a stroke of genius.

It was in the baking hot summer of 1976 that Rolf woke up one Sunday morning dripping in sweat and decided he needed a pool. A quick flick through the Yellow Pages and a man from Dore was at his house two hours later pricing it up.

The house where Rolf lives is a two-mile long country lane with only 20 houses on, the first being half a mile up. But the builder said he could sort it, no problem. Well only one small problem.

“He asked me where the mains were for the water, so I pointed to the sky. We didn’t have any mains connection then. He looked at me like I was crazy – how can you have a pool with no water? But luckily for me there is a reservoir a javelin’s throw away from my house.

“My old boss lent me a lorry with a 2.5-gallon tank on the back. But the pool is over seven-foot deep and needed 11,000 gallons to fill it. I fell in fully clothed at the end of the day I was that exhausted. We finally had mains water connected eight years later so it was much easier to fill after that.”

Since having the pool installed, there have been plenty of stories to tell, such as the time Jacqueline found a streaker taking a swim one October.

Another time, Rolf phoned the police to report a miniature polar bear in the shallow end.

“I was woken up at 2am one morning to the most frightening, howling noise like something from a horror film. The pool was covered up, but I could see this polar bear’s head poking out. When I phoned the police they asked me if I’d been drinking!

“I went out in my pyjamas and approached this huge beast with a net on the end of a stick which it didn’t go for, so I got a bit closer and could see a collar with a tag on. I called the number and the owner answered the phone after one ring and said it wasn’t a polar bear but a 13-stone Pyrenean Mountain dog that had gone missing from Stocksbridge that afternoon.

“He told me it wasn’t vicious and was daft as a brush. I was quite strong back then so I managed to get my arms under the dog’s shoulders and pull it out the pool but ended up with the thing laid on top of me. As if I wasn’t wet enough the dog then decided to shake itself off, covering me in water. His owner came to collect him shortly followed by a police car with an inspector in who had come to see the polar bear for himself. Even he agreed it could have been one!”

Rolf’s life reads much like a film script and many actors would be lining up to play the title role if Rolf’s story was turned into a biopic. But he’s also appeared on the silver screen in war film, of all things. While on holiday in Spain in 1989, Rolf was approached by a producer and director who were looking for a replacement for one of the actors had taken ill.

“I was half cut and thought one of my mates was winding me up. The next thing I knew I was being measured for an admiral’s uniform. Luckily for me one of the editors from Granada TV was staying in the same hotel and managed to document it with photos for a story or nobody would have believed me!”

Unbelievable is one word to describe his life; from boy to man his journey has been incredible. Not only did he escape the Nazis as a young child, but he has also had another battle – this time against cancer – for the latter part of his life.

“I’m a very greedy person; I’ve had four different types of cancer. I was diagnosed with prostate cancer 25 years ago, and that didn’t kill me, so then it was non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma which they said was not curable but treatable which cheered me up a bit. Then one day they told me they couldn’t treat it anymore because I didn’t have it anymore. They’d somehow managed to cure it. Then I got skin cancer caused by stopping work at the first sight of sun. And last year I was diagnosed with lung cancer.

“Every time I go for my check up the nurses hug me. Not because they love me but because I’m still here. On my demise I joke with them that I’ll leave my body to the Hallamshire for science. They can even stuff it if they want.”