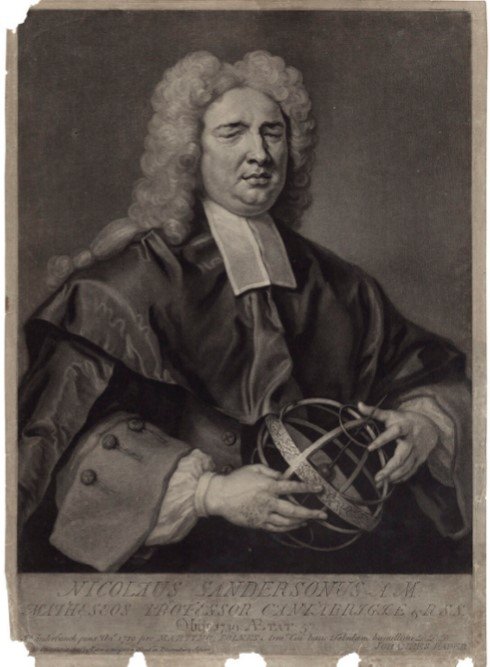

He may have lived almost all of his life in complete darkness, but the legacy of Barnsley-born blind genius, Nicholas Saunderson, has shone brightly throughout the history of mathematics for almost 300 years.

Yet despite his extraordinary achievements in the face of adversity, his name has been somewhat eclipsed in his hometown’s history books.

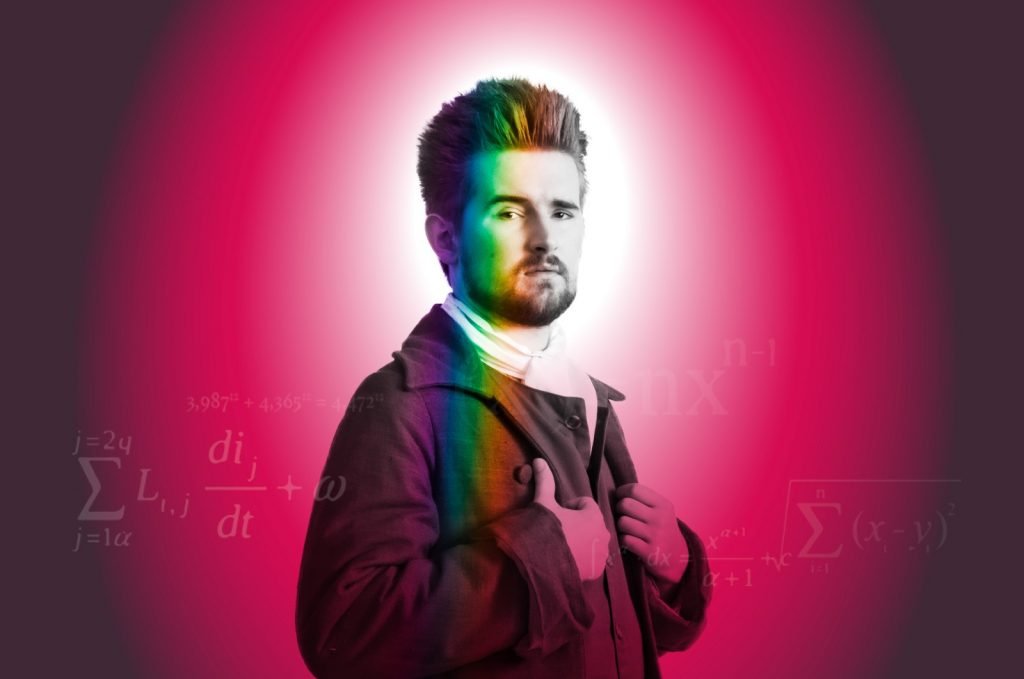

Following a relentless 17-year project in which he’s quit his job twice to pursue it, former headteacher, Andy Platt, is proud to rightfully reinstate Saunderson into the limelight and expose his inspirational story with a professional musical production called No Horizon.

No Horizon chronicles the life and workings of Saunderson who went on to hold one of the most prestigious academic posts in the world, the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge University, for 28 years in spite of losing not only his eyesight but also his eyes to smallpox as an infant.

Saunderson sits amongst some of the finest mathematics brains of all-time including Isaac Newton, Charles Babbage and Stephen Hawking who have also held the same chair. Yet Saunderson’s status doesn’t seem to have derived the same degree of recognition than that of his peers – until now.

From Thursday 19th March until Wednesday 15th April, No Horizon will embark on its debut professional tour of some of Yorkshire’s finest theatres thanks to funding from the Arts Council and the Foyle Foundation.

“When I started this project almost 20 years ago, few knew about Saunderson which was shocking to me. One of my main aims is that the people of Barnsley take ownership of this remarkable man and his story,” Andy says.

Saunderson was born in Thurlstone on the edge of Penistone in 1682, the son of an excise man, or tax collector. After being blinded at 12-months-old, his life should have been a mundane one filled with inequality and poverty; yet he did everything in his power to broaden his horizons and deviate from this fate.

He rebelled against the lack of aspiration and opportunities for the blind. He didn’t want a humdrum life and was shaped by the perception and expectations others had of him.

In an age before braille, a young Nicholas is said to have taught himself to read by tracing the letters on gravestones at St John the Baptist Church in Penistone. In his youth he devised a palpable arithmetic board to help him with his calculations; sort of like an abacus but using pegs to count.

He was fluent in French and was also taught Latin and Greek at Penistone Grammar School. After being tutored in algebra and geometry by local gentry, he went to Attercliffe Academy for a short period before deeming their teaching far below his capability.

With no formal qualifications or family financial backing, at 25 he decided to leave Yorkshire for Cambridge University, not as a student but as a teacher. Saunderson was an exponent of Isaac Newton’s theories and he impressed the college so much that he was allowed to give lectures at the Newtonian School of Mathematics and Physics before being given honorary bachelor and master’s degrees.

Over the next 20 years, he would become the fourth Lucasian Professor, be elected into the Royal Society, and be made a Doctor of Law by King George II.

An incredible feat for someone with such humble beginnings, let alone someone without sight.

Andy lived in the same village where Saunderson was born but was only first introduced to his story in 2000 by a colleague at Springvale Primary School in Penistone where he was then deputy head.

“I would be doing assemblies at school about aspirations and people who had achieved great things against their own struggles, people like Helen Keller and Florence Nightingale. Yet here was a man from just a mile down the road who was the epitome of just that,” Andy says.

Andy became fascinated by Saunderson’s story and, in a time before readily available internet access, went to Barnsley Archives to delve into his background.

Here, he found a thesis written about Saunderson by a Canadian maths lecturer called Jim Tattersall. In a strange twist of fate, the paper included an interview with a sculptor from Thurlstone called Jim Milner who was a direct descendant of Saunderson – and who Andy happened to have bought a house from.

Using Jim Tattersall’s findings as the bulk of his research, Andy decided Saunderson’s story needed to be told and so first set about developing songs and a loose script in 2003.

“I’ve got no theatrical background, but I was part of a band years ago that I wrote music for and was also involved in producing school musicals. Whilst I was confident in my song-writing ability, that’s as far as it went.”

Andy partnered with local businessman, Max Reid, who would become co-producer with his wife Helen, to form Right Hand Theatre with the dream to take the musical to a national audience.

In 2006, Andy left his role as deputy head to focus on No Horizon for a year with the aim to promote the concept to West End producers.

However, the year proved fruitless and Andy returned to work at Springvale.

The project lay dormant for almost a decade before Andy and Max decided to revive it for the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2016.

To get the full benefit of the Fringe, they were encouraged to do the full month’s run which Andy says was the best month of his life.

“This was our chance to get No Horizon in the shop window and be seen by influential people. We weren’t sure how the response would be outside of Yorkshire, especially with the strong dialect. But the heritage and human-interest angle of the story is what audiences latched on to.

“It was a real game changer. We saw the power it had to entertain, inspire and move people, particularly those who’d had similar life challenges to Saunderson.”

Audiences grew from 30 to 200 and it garnered strong reviews from critics and theatregoers alike, with Chris Evans even dubbing it the ‘Yorkshire Les Mis.’

It also attracted interest from the Arts Council who funded research and development work which enabled Andy and Max to assemble a creative team made up of internationally recognised people in the hope of propelling it into a professional production that could tour regionally.

Andrew Loretto, who is visually impaired, joined the team as director, along with Sally Egan from Opera North as vocal director and the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Lucy Cullingford as choreographer.

Around the same time, Andy made the decision to quit his job for a second time to concentrate on No Horizon full-time.

“When we got back from Edinburgh, it was like the bubble had popped and I was back to the reality of accountability. I was headteacher by then and when we went up to the Fringe we were due an Ofsted inspection at the same time. It was a massive challenge to prepare well for both events – they were two completely different worlds but knew I just had to follow my heart this time.”

Since then, Andy has been working with dramaturg, Richard Hurford, to adapt the story for the professional stage. The storyline and music are still the same but the retelling has become more contemporary.

They also have a full costume and set design thanks to Lydia Denno and Sophie Roberts.

One of the main changes has been the cast. For the Fringe, there was around 30 people involved which included 18 mainly amateur actors.

The main cast has now been cut back to just six lead roles made up of professional actors who are adept at working on the theatre stage.

Saunderson is now played by Doncaster actor, Adam Martyn; a visually impaired graduate of Sir Paul McCartney’s LIPA (Liverpool Institute of Performing Arts.)

“It was a tall order for us to find a great actor and singer who could do an authentic accent and was visually impaired or could have an understanding of being blind. But Adam answered our prayers.

“Saunderson was a classic Yorkshireman who called a spade a spade. His way was the right way and we needed the right person to do him justice,” Andy says.

No Horizon delves into his personality as a vivacious, witty and stoic character with an outstanding reputation as a teacher of maths and natural science who put his own research aside in favour of giving lectures packed with students for up to eight hours a day.

He had not the use of his eyes but taught others to use theirs. Interestingly, he became known for his talks on the theory of light and colour which is remarkable for a man who would have only known darkness due to having his eyes removed.

It also looks at the correlation between him being passionate but outspoken, sarcastic but honest, and the circles he mixed in at Christ’s College including his staunch friendships with other academics such as Isaac Newton, Edmond Halley and Roger Cotes.

No Horizon also touches on his life away from the algorithms, formulating a picture of his role as a husband and father. He married a rector’s daughter, Abigail Dickons, in 1723 and the couple went on to have two children. The family lived in Boxworth just outside of Cambridge before Nicholas died of scurvy in 1939 aged 56.

The tour kicks off at Barnsley Civic on Thursday 19th March before moving on to Halifax Viaduct, Leeds City Varieties, CAST Doncaster, Harrogate Theatre, York Theatre Royal and Millgate Arts Centre during its month-long tour.

“Hopefully there will be life beyond this inaugural tour. Originally it was just a pipedream but who’s to say we can’t do a national tour or reach the West End. The dream lives on and I can’t believe we’ve even got this far.”

For more information about No Horizon, full tour dates and where to book tickets, see their website www.nohorizonthemusical.com