The main downside to the strike was the breakdown between communities and law and order.

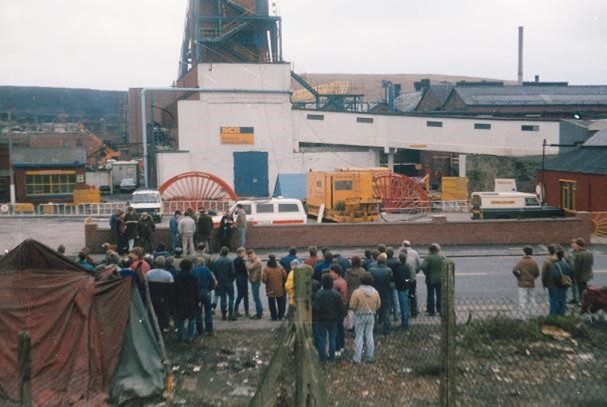

Arthur Scargill resurrected his idea of so-called ‘flying pickets’ – striking miners sent to specific plants, usually to prevent the transportation of coal. Miners swapped a full-time job down the pit for full-time picketing, trying to discourage others from working.

Police manning was at an unprecedented level with 1.5 million deployments from 43 forces. If they could stop the pickets coming in, they’d stop the problem.

The police were there to do a job, working to protect the rights of both striking and working miners. But striking miners became indignant at being dubbed troublemakers and lost respect for the police for their behaviour on the picket lines. Their approach was Orwellian, physically breaking picket lines up and being overzealous in their reaction.

It was a game of cat and mouse. Police roadblocks prevented crowds of picketers from congregating at one place. A tactic to avoid a breach of peace. But one that was like a red rag to a bull.

“The police became the enemy,” says Bruce Wilson, a former miner from Silverwood Colliery. “In our minds, it was a free country so who were they to tell us where we could and couldn’t go? I had my grandad’s war medals after he fought for our freedom. We became wise to their tactics but got battle fatigue as the strike went on, just hoping to get home safe each night.”

Yorkshire’s striking miners were often concentrated on infiltrating Nottinghamshire, the two counties having opposing views of the strike. In Yorkshire, 97 percent of the 56,000 workforce were still on strike at the end of the 1984, numbers boosted by the militant South Yorkshire miners. In Nottinghamshire, it was just 20 percent of the 30,000 workforce.

In the first six months of the strike, over 164,000 pickets were turned away in Nottinghamshire.

Flying picketers like Bruce had to use ingenuity and determination to get past the roadblocks. They spent hours planning routes, using country lanes, disused railways lines, farm tracks – wherever you could get a car down, they tried it.

Sometimes it worked, other times they hit a wall of police and found themselves on their way back to South Yorkshire.

But they were never deterred. Striking miners got paid £1 a day for picketing, and the driver got fuel. If you were a single lad, you relied on that picket money – it was all you had in the world.

“My dad had a Jag with a private reg plate so the police never thought he was a picket. But there were times when we were picketing in Nottingham and cars that parked in front of pit houses by the railway lines got smashed up by the police. They looked at our tax discs and knew we were from Yorkshire. There was funding available from the NUM to keep cars on the roads but we spent a lot of money fixing cars up with second-hand parts we found at scrap yards,” says Chris Kitchen.

As time went on, picket lines got weaker and frustrations got stronger. The fabric of society was starting to tear. Thousands of miners were arrested, fined, imprisoned or sacked, some never to work again.

Tragically, two miners were killed while striking. Davy Jones was a Yorkshire miner killed a week into the strike when he was hit by a brick while picketing at Ollerton in Nottinghamshire. Joe Green was killed in June, a few days before the Battle of Orgreave, after he was mown down by a lorry while picketing Ferrybridge power station in Yorkshire.

As more miners went back to work towards the end of the year, tensions were at an all-time high. Miners were pitted against each other, both sides fighting for what they believed to be right.

Brenda Boyle remembers being threatened with arrest if she shouted at a neighbour who had returned to work.

“Police were on the street protecting him. The street was lined with women and were told not to shout at him or we’d be locked up. Someone painted ‘scab’ on his house and he blamed me. I told him I wouldn’t ever paint it on his house, I’d have painted it on his face.”

Brenda perhaps felt strongly than most about what miners were being put through. She says her four sons all experienced multiple beatings from police, but were tarred as hooligans by the rest of the community.

“You don’t forget it. It was horrible when it was happening. I used to get on the bus that came from Ravenfield and these other women would be saying ‘that’s her with them kids who’ve been fighting bobbies.’ My anger couldn’t put up with that, so I told them in no uncertain terms to get their facts straight. The bus driver pulled up and threatened to kick the other women off.”