What led to the Miners’ Strike?

There are few areas in our region that have not been blighted by coal extraction at one time or another.

Coal had been worked in South Yorkshire since the 13th century, initially in Silkstone and Masbrough. By the 16th century, improved transportation and engineering, and the expansion of the metal smelting industry, meant the demand for coal was high.

The Barnsley seam was the principal seam in Yorkshire; 600-square-miles of coal that exceeded others in thickness and quality. Other seams in the South Yorkshire coalfield included Silkstone, Parkgate, Thorncliffe and Haigh Moor.

Coal from South Yorkshire was high grade and had a worldwide reputation. It fired the Industrial Revolution for more than 150 years, being used for power generation, manufacturing, and to drive steamships and railways.

After 1860, the location of collieries was dictated by proximity to the railway. This enabled more tonnage to be distributed compared to the previous transportation via canal ways.

The turn of the 20th century saw a rapid rise in output of coal. In 1851, South Yorkshire produced 3.4 million tonnes of coal. By 1924 this had increased almost tenfold to 31 million tonnes.

Increasing demand for coal ultimately led to an expanding workforce. In 1851, 11,750 people worked in South Yorkshire’s coal industry; by 1924 this figure had topped 122,500.

Collieries were ether owned by iron or steel manufacturers like the Walkers of Masborough or Newton Chambers of Chapeltown, with coal being ancillary to their business, or by those who traded coal like the Earls Fitzwilliams of Wentworth Woodhouse.

However, in 1947 the coal industry was then nationalised by Labour Prime Minister Clement Atlee with the promise of modernisation and reorganisation under the National Coal Board.

Colliery owners were collectively paid over £164 million for their assets. The NCB inherited 958 collieries, 55 coke ovens, 151,000 pit houses, and a workforce of 796,000.

The average colliery produced 245,000 tonnes of coal a year, with a total output of 184 million tonnes. The NCB aimed to increase this to 250 million by 1970.

But cracks soon started to show, fuelled by the correlation between coal and oil. As consumption of cheaper oil increased, the use of coal declined. In 1958, demand had contracted by 33 million tonnes, resulting in the closure of 85 pits with a loss of 30,000 jobs.

What followed in the 1960s was another accelerated closure programme affecting a third of the workforce. The number of pits went from 698 in 1961 to 292 ten years later.

The industry was reorganised in 1967. The 92 collieries in Yorkshire were split into four new self-contained areas: Barnsley, Doncaster, North Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire.

South Yorkshire’s boundary stretched from Wath Main and Barnburgh down to Shireoaks and Manton, incorporating 22 pits with its headquarters at Manvers. The Barnsley coalfield had 30 pits from Caphouse and Criggleton on the West Yorkshire border down to Smithywood and Barley Hall on the Sheffield border, with its HQ at Grimethorpe.

Despite the changes, the NCB’s coal activities were still running at a loss in 1970, putting pressure on the board to hold down pay increases. Miners’ wages had not kept pace with those of other industrial workers. In the 1950s, wages were 25 percent higher than other manufacturing industries. By 1970, miners were earning 3.1 percent less than the average worker in manufacturing.

A strike was called on 9th January 1972 and lasted for seven weeks, ending on 28th February with miners winning two-thirds of their pay demand.

The next ten years saw another period of decline. The richest seams had been worked out and the remaining coal was becoming harder and more expensive to reach. A proposed solution was mechanisation to combat the overcapacity of production, but this came at the cost of redundancies.

In 1981, Margaret Thatcher planned to close 23 pits but plans were scrapped after the National Union of Mineworkers ordered a national ballot. Thatcher backed down after realising there wasn’t enough coal reserves to fight a mass walkout; there was only six weeks of stock but they needed at least six months’ worth.

But the threat of a strike would eventually transpire three years later.

Output needed to reduce by four million tonnes. Word got round that there was a hitlist of 20 pits set to close, sparking fears that this would be the death warrant for the industry.

In South Yorkshire, the crux of that list was Cortonwood. The NCB’s area director for South Yorkshire believed he could make the required saving of 500,000 tonnes by closing just one colliery. It wasn’t a dying colliery; they had a good production record and only made small losses. But there was apparently no demand for the grade of coking coal produced at Cortonwood, so the NCB deemed it wise to close. Miners would be relocated to other pits in the area.

But this decision came at a fraught time. Many had just been transferred to Cortonwood from Elsecar after that had closed, with the promise of job security for at least another five years. Now they were being told the pit would shut in just five weeks.

If the NCB could shut Cortonwood at such short notice, the NUM believed no pit was safe.

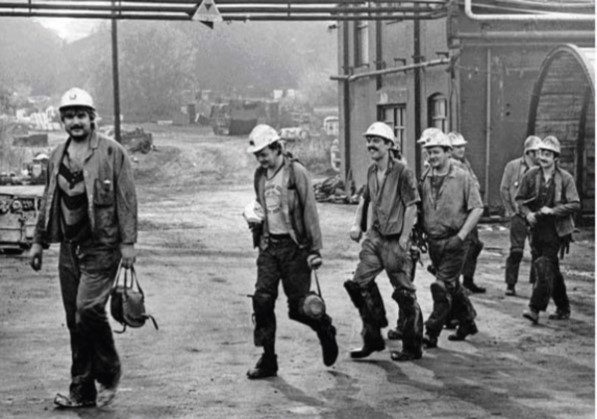

Miners walked out of Cortonwood and the Yorkshire branch of the NUM sanctioned a strike across the county. Others followed suit at pits like Manvers, Silverwood, Cadeby and Kiveton Park. By the end of the month, more than half of the workforce was on strike – around 100,000 miners from 80 pits.

NUM president Arthur Scargill called for national strike action but controversially didn’t conduct a national ballot first. This would soon come back to haunt him.

Not everyone was on board with the idea of a UK-wide strike. While miners from Yorkshire, the North East, Kent, Scotland and South Wales downed tools and took to the picket lines, those in Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire, South Derbyshire and North Wales carried on working.

Consequently, the strike split the workers, some of whom went on to form the breakaway Union of Democratic Mineworkers. It led to bitter tussles between miners who carried on working throughout the strike and pickets who were quick to label strikebreakers ‘scabs’.

The conflict sowed bitter divisions, ripped apart entire communities, set police against the public in violent confrontations, and changed many areas of the country beyond all recognition.

After 11 months, three weeks and four days, the strike was called off on 3rd March 1985.

After the strike, collieries began to close in their droves. By the end of 1985, 23 pits had been shut making 18,500 redundancies. In South Yorkshire, these included North Gawber, Cortonwood, Brookhouse and Yorkshire Main.

The combination of cheap imported coal from Australia, Poland and the Netherlands with the privatisation of electricity in 1990 reduced the demand for indigenous coal. More pit closures followed until there were just 53 left by 1992, with another 31 earmarked for closure.

In 1994, the industry was privatised after 47 years of state control. RJB Mining, which later became UK Coal, took over ownership of 17 collieries including Maltby and Rossington in South Yorkshire. RJB’s owner later acquired Hatfield Main.

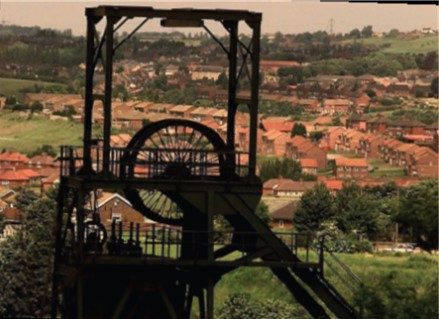

Rossington closed in 2007, followed by Maltby in 2013 and Hatfield in 2015. Selby’s Kellingley colliery, or the Big K as it was known, was the last to close in December 2015, marking the end of deep coal mining in Britain.