It’s one of Barnsley’s oldest in-use buildings and is steeped in historical intrigue. But in contemptuous irony, the Mill of the Black Monks is at imminent risk of becoming a paradoxical quagmire from the very thing that once powered it – water.

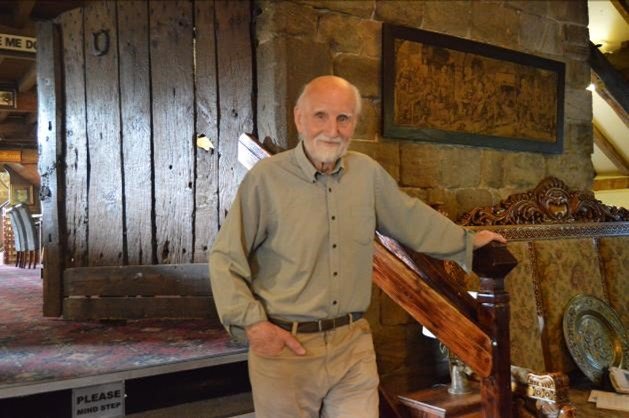

This magnificent mill, thought to be one of the town’s earliest examples of industry, has been damaged by flooding in recent decades, with the risk only set to rise as climate change takes hold. But its owner, 83-year-old Malcolm Lister, who has spent half his life tirelessly trying to restore the medieval building, is now campaigning for a divine intervention to prevent the Mill of the Black Monks from being silenced forever.

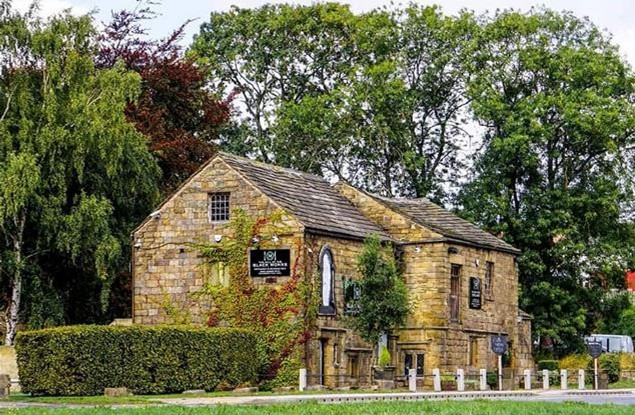

Sitting on the edge of Grange Lane, the busy road which connects Stairfoot to Lundwood, hundreds of cars will drive past the Mill of the Black Monks every day – yet few will be aware of its significance to Barnsley history.

The former watermill was built by and for the Cluniac monks in 1145AD to service the neighbouring Monk Bretton Priory. Adam Fitzwain, grandson of wealthy Saxon landowner, Ailric, donated the land to the Cluniac monks from Pontefract to build a secondary monastery in Barnsley. In his bequest, he is said to have included a ‘milne’. However, evidence of Saxon and pre-Norman Conquest activity has been found, leading many to believe there was an original mill pre-dating the Priory by some 500 years.

The monks lived a simple life on the site of the abbey and worked throughout the town managing various parishes, letting properties and working the coal and ironstone. At the mill, corn could be milled round the clock as the nearby River Dearne flowed day and night. There were two sets of millstones – one at each end of the building – which may even have been used for means other than grain at some point.

By 1281, the monks had disaffiliated with the Cluniac order following long-running conflict regarding the appointment of priors. It became an independent Benedictine institution until the Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VII saw the priory closed for ecclesiastical purposes in 1538.

But what about the mill?

When Henry VIII’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, came to sequester the priory, he brought with him friend and King’s commissioner, William Blythman, who bought the site including the mill. During this time, the former priory was pillaged for its materials; the church ended up at Wentworth and the old bells were melted down for their silver content. But the mill escaped unscathed.

In 1589 the estate was then bought by George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewbury, to add to his and wife Bess of Hardwick’s impressive property portfolio which included Sheffield Castle, Chatsworth House, and the old Hardwick Hall. Talbot was the gaoler, or keeper, or Mary Queen of Scots for 15 years and she spent her time under house arrest at his various seats; it is not known whether she ever visited the mill.

Eventually, the mill and estate passed down to Talbot’s granddaughter, Lady Mary Armyne, who owned the mill with her husband William. She added the big door to the front which still remains. Lady Mary was a pioneer in many ways; she built hospitals for the poor, donated money to educate native Americans, and built a row of six almshouses next to the mill for widows. These 17th Century buildings were sadly knocked down in the 1960s and little remains of her legacy to Barnsley, except for a portrait hanging in the mill.

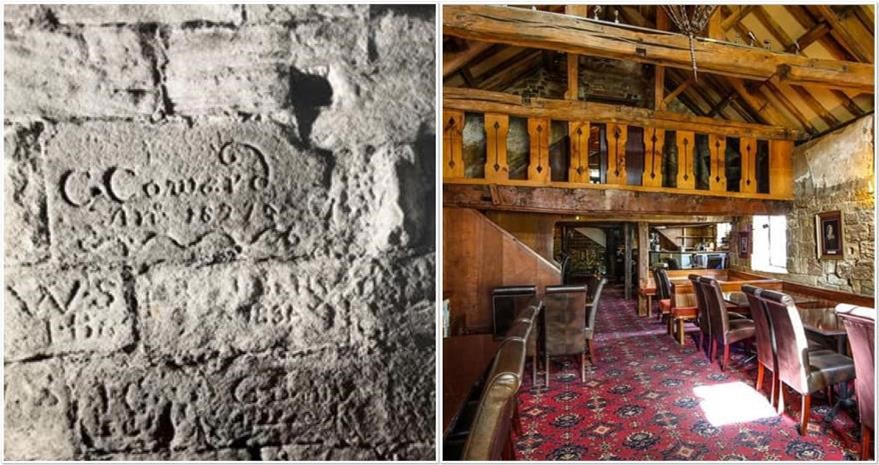

The building remained a working mill for some 350 years following the Dissolution and various examples of workings and graffiti from the former millers can still be found throughout the building.

It became state owned in the 1880s when Barnsley Corporation bought the site and closed the mill with it eventually being used as a paint store. Some 100 years later the mill then came into the ownership of Malcolm, an esteemed, award-winning architect who saved the building from destruction.

Historian, John Hislop, who worked in conservation for Barnsley Council at the time, blew the whistle on plans to demolish the historic mill and replace it with a visitor centre and car park to his collaborators at Barnsley Archaeological Group, of which Malcolm was a founder member. Former councillor, Tom Sheard, then agreed the building could be sold to Malcolm in the late ‘80s.

Malcolm, who now lives in Wakefield, grew up in Darton and went to Barnsley Grammar School which is where he first saw a poster for interviews at an architect business on Regent Street in the town.

“My dad was a miner at Woolley colliery and mum was a cleaner. As I was approaching the end of my schooling, Dad asked me ‘what’s tha’ wanna be?’ which is probably one of the only times he spoke to me! I don’t really know where the idea to be an architect came from, but it sounded interesting,” Malcolm says.

He worked five-and-a-half days a week at the Regent Street office and studied at night.

“I worked there for nine years but it felt like it took 4,000 years to qualify as the training was very involved. We had to send all our designs down to London to be assessed and I didn’t even have a portfolio, so I made one from hardboard sheets fastened together with shoelaces.”

In the 1980s, there was a competition to design the new headquarters of the National Union of Miners, commissioned by the NUM leader Arthur Scargill, who was moving their base to Sheffield from London.

Malcolm, who was 46 at the time, beat 38 other applicants to have vision turned into a reality. His winning design, which he called Unassertive Dignity, was inspired by the humble life of a miner he’d come to know so well.

“Miners aren’t here to impress. They’re ordinary working people who get mucky and dirty but are still dignified and I wanted my building to represent the people I come from. When I was planning my design, I asked my dad what music I ought to play to motivate me. Of course there was only one answer – brass band music. It was this juxtaposition that truly resonated with me.”

His design was completed in 1988 but was sadly only used for four years before the operation moved to Barnsley at the collapse of the mining industry. Today, the glass fronted building, which is located by Sheffield City Hall, is now home to various food and drink outlets.

Throughout his career, Malcolm has restored various historic buildings across the country, including the Counting House in Pontefract for which he won four national awards. And while the NUM building brings him the most pride, his commitment to the Mill of the Black Monks has been a real labour of love that has caused more heartache than he ever imagined.

Over the last three decades, Malcolm has had many obstacles thrown at his desire to give this important piece of Barnsley heritage back to the people. But with every hurdle, he has remained optimistic that his dream will become a reality eventually.

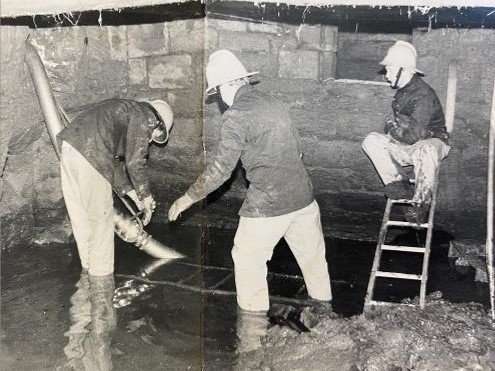

When he first purchased the mill in the late ‘80s, Malcolm undertook a mammoth task of raising the entire building up six feet which would have left most people running for the hills. At some point in the late 19th Century, a brick sewer was installed straight through the middle of the mill’s lower floor which needed diverting before any works could begin. Because of the huge drain, and the remains of the original river and weir nearby, the mill had been buried and needed winching up to ground level.

“We dug this big trench around the perimeter of the building and my sons, Mark and Guy, helped me shovel 190 tonnes of mud from the lower floor out of a little hole in the wall. When we’d finally managed to raise the building up, people were driving past pipping their horns and shouting ‘you’ve done it, cock!’ I got the trench filled in pretty quickly so that I could be the first person in decades to walk through the front door which was just glorious. We must have been barmy, but the building is still here because of it.”

The mill has had several extensions over the years which has added to its quirk and charm. There were originally two separate buildings which were ultimately connected by Malcolm. But because the foundations of both were not aligned, it has resulted in a bent and bowed appearance which can be seen in detail in a matchstick model of the mill which was created to scale by the late Harold Semley of Worsbrough Dale.

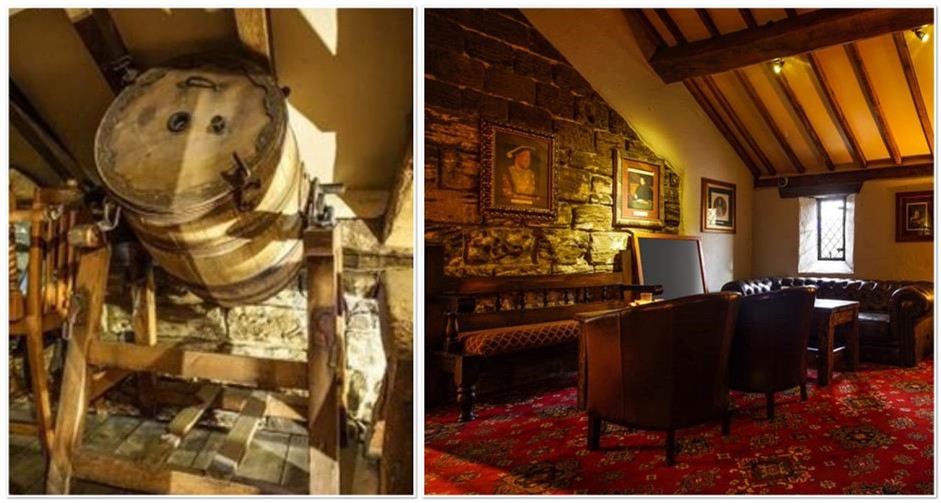

Inside the building, which is now used as a restaurant, there are many original features which have been preserved by Malcolm. The timbers in the open-beamed roof are as they were in medieval times and there are remains of an old fireplace where the monks would sit and log what the miller had been doing each day. There are even outlines of the old trap doors still visible in the original flooring. The millstones have since been removed, but evidence of the working mill, such as the iron pulley system and original winnower which used to separate the chaff from the corn, still remain.

Etched into the exquisite masonry are the initials of previous millers and monks, and portraits of all the former owners hang on the solid stone walls. The décor has been sympathetically designed for diners to feel like they’re stepping back in time to enjoy a sumptuous banquet in Gothic surroundings.

It looks so authentic, even Malcolm’s late mother commended the monks for their ironwork on the mill’s spiral staircase – not aware it was indeed her son who had had it made and installed almost five centuries after the monks moved out.

After restoring the past, in 1991 Malcolm drew up a scheme that would protect the mill’s future. His plans include creating a cloister in recognition of the monastery, adding overnight accommodation, as well as craft shops and a function suite. His scheme continues to be thwarted despite having Cabinet and planning approval and the promise of finance from the former City Challenge.

Malcolm now feels the building deserves to have its Historic England listing from grade II – which it was over 30 years ago when it was buried in six-foot of mud – to grade II*. He is now working with Friends of Monk Bretton Priory, who voluntarily manage the upkeep of the monastery ruins which are a Scheduled Ancient Monument, to come up with a solution.

“We are all in agreement that the priory can’t exist without the mill, and the two should continue to work harmoniously as they have done for 900 years. The mill has got the ideal facilities for visitors to the priory. But my scheme, particularly the addition of accommodation, would help boost its international tourism interest.

“I’ll probably never see my vision come to fruition now. I was 52 when I started and I’m now 83. But my son, Guy, will continue to fight. He’s the same age now as I was when I began this battle and he’s ten-times cleverer than me. He’s head of architecture for a national company now, but there’s nothing he hasn’t done to support me – he even pulled pints behind the bar.”

Before any works can take place, the mill now needs adequate flood defences installing such as a wall to the roadside and flood gates. The main issue is that the site of the mill has been classified as an allocated flood storage area which means, when the area floods – which there is a high risk due to its proximity to the river – the water is stored in that vicinity. Malcolm says this decision was made based on aerial images which neglected to pick up the mill building. But it puts the mill at severe risk of collapse if (or more likely when) flooding next occurs.

Malcolm is now calling on the public to support his plans by signing a petition. Without our support, the mill and its closely recorded history might not be here much longer, the piece of invaluable heritage destined for a watery grave.

“I’ve never made any money out from renovating buildings like the mill, but it’s never been about financial gain. I just absolutely love doing it. Knowing that my work over the last 30 years has given jobs to the people of Barnsley is something I’d never dreamed of. But I’m just an instrument in all this.

“I’m so proud of the friends I’ve made and give credit to people like John Hislop and Ken Jackson, a retired senior planner, for standing up and speaking out 40 years ago. The former labour leader Ron Fisher once said anyone other than this guy – meaning me – would have given up. And perhaps I’m stupid for all the heartache I’ve experienced because of it. But life is a mirror and whoever looks back is who you are.”

You can sign Malcolm’s petition here.